Imbaza Mussels, established in Saldanha Bay in the Western Cape in 2012, is a substantial operation, both by South African and world standards. It is 30ha in size, with one raft per hectare.

Each raft has 800 mussel ropes hanging 6m into the sea. That’s 144km of mussel rope, roughly the distance from Saldanha Bay to Cape Town!

READ Aquaculture for beginners – Part 1

“The ropes create a substrate for mussels to settle on. In nature, they settle on rocks or mooring lines. No mussel spat [larvae] is planted on the ropes; it’s all natural spat fall and recruitment,” says Imbaza general manager, Vos Pienaar. (‘Recruitment’ is natural population increase through the growth of individuals and the constant arrival of new spat.)

Vos explains that mussels, triggered by temperature and lunar cycles, release their eggs and sperm into the sea. The eggs are fertilised immediately and these develop into swimming mussel larvae within 24 hours. Many end up as a rich food source for other marine mammals.

“Three weeks later, they settle on a substrate. This is where our mussel ropes come into play. The larvae pack onto the ropes and continue growing.”

Rolling production

At this stage, the mussels attached to the ropes are thinned out so that they don’t consume each other’s nutrients and can grow optimally. They feed by filtering sea water to extract nutritious phytoplankton.

The shell is formed through the binding of calcium and carbonate, and takes 12 months to reach a marketable 9cm.

Harvesting takes place daily – weather permitting – and a combination of large and small mussels attach themselves to the ropes. Imbaza staff pull the working raft up alongside the mussel raft and remove the mussels by beating the ropes on the deck.

The detached mussels are then loaded with a spade into the declumping machine, where they are washed. Market-sized mussels are retained while smaller ones are deposited in baskets.

From here, the mussels are moved to a slatted sorting table, where undersized ones drop into baskets. Market-sized mussels are packed into plastic crates and transported to the factory in Velddrif for processing.

The undersized mussels are put into a long, sock-like cotton net with a mussel rope running through its centre, and placed in the sea. Within two or three weeks, the undersized mussels have reattached themselves to the rope and the cotton casing has rotted away. It takes these reattached mussels six to seven months to reach marketable size.

It takes these reattached mussels six to seven months to reach marketable size.

Imbaza Mussels harvests about two rafts – 1 600 ropes – per month, and harvesting continues throughout the year, regardless of the season. There is a temporary setback just after the spawning season, which is usually in spring, as the mussels lose weight. But they recover their condition in full within a month.

Red tide and other toxins

According to Vos, the greatest disruption to harvesting is red tide or algal bloom, which is a serious factor from late summer to early autumn, and can occur at any time from February to May.

Ironically, mussels grow fatter by consuming the blooms, but their flesh then causes a variety of ailments in humans, ranging from a simple upset stomach to neurotoxin-induced breathing paralysis. Once the blooms disappear, it takes about three weeks before the mussels are considered ‘clean’ again.

“We don’t harvest anything during this time,” says Vos.

This year has been a particularly challenging time for Imbaza. Harvesting had to be stopped in January for four months as toxins in the seawater caused diarrhetic shellfish poisoning, resulting in stomach ailments in people who consumed the affected mussels. These conditions were ascribed to the south-easterly wind not blowing for long enough during summer.

“At least our stocks weren’t lost. It just interrupted our production cycle,” says Vos.

Monitoring for toxins is stringent and ongoing.

“We measure water quality every day and screen [samples] for toxins in the laboratory at least twice a week,” says Vos.

“If we identify toxic plankton, we intensify the laboratory screening and stop harvesting immediately when it reaches a certain level. Then, when the plankton has disappeared from the water, we still wait for the toxin levels in the mussels to drop below the internationally [acceptable] level.”

The company uses a R2 million liquid chromatography mass spectrometer to regularly test toxin levels in the mussel meat.

Markets and margins

Vos says that mussel farming produces a small profit margin. “Mussel farming is not like abalone or oysters, which have high margins.”

Currently, global mussel production amounts to two million tons per year, and takes place mostly in China, Chile, Scotland, France, New Zealand and Spain.

“So if you have overproduction coupled with a recession in the destination market, you have a big problem. Luckily the exchange rate helps to keep out cheap imports and we only supply the local market.”

Imbaza currently supplies roughly 50% of the SA market.

A total of 2 000t/year of mussels is produced in South Africa by the companies in Saldanha Bay, and Vos estimates that these have a realistic capacity of approximately 4 000t/ year, which makes South Africa a small player globally.

“If your production cost isn’t as competitive as, say, a mussel farmer in Spain – most of which are small family-run businesses – you’re going to go out of business. Mussel farming sounds exotic, but the reality is quite different.

People misjudge their yield, thinking it will be 60kg/ rope, but the reality is closer to 30kg/ rope.”

A kilogram of mussels harvested by Imbaza Mussels contains about 30 molluscs each 9cm long. Vos says the South African market prefers larger mussels; in contrast European consumers tend to choose smaller mussels.

The shelf life of a fresh, live mussel is only two days under temperature-controlled conditions as a mussel shell

doesn’t seal perfectly and therefore the molluscs lose moisture. However, the market for mussels is growing faster than that for oysters, because mussels are more versatile, Vos says.

Saldanha Bay: optimal mussels

In aquaculture, explains Vos, the quality of the site depends on the quality of the water, protection from currents, absence of pollution and good water circulation.

In this regard, Saldanha Bay is unique in global terms as it offers good protection for the mussels and is one of the most nutritious sea environments in the world, with the Benguela current system offering arguably the most nutritious water in the world.

“The breakwater built by Transnet in Saldanha harbour gives us even more protection,” he says.

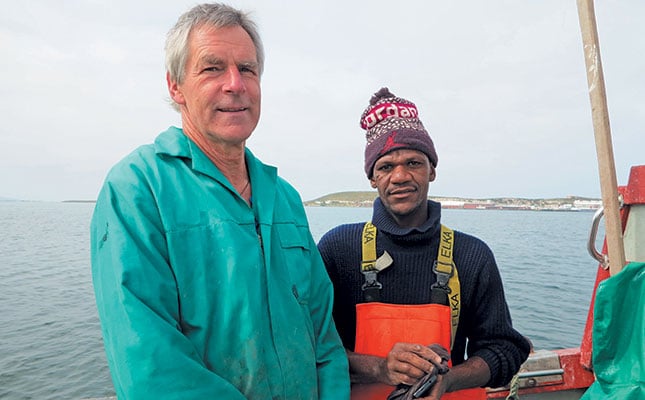

Black empowerment

Imbaza Mussels is a majority black-owned company and has its origin in other mussel-producing operations. Blue Bay Mussels bought out Sea Harvest’s mussel farming operation in Saldanha Bay, which had six employees, as an empowerment project.

Each employee had a raft and an invoice book, and started farming mussels on his own.

The six then broke away from Blue Bay Mussels to form Imbaza Mussels, which now has a black shareholding of 67%. Today, there are 17 staff members, one boat and 30 rafts. Imbaza Mussels has also created 100 jobs at the Velddrif factory.

Asked about future expansion, Vos says: “With the model we’re running, 30ha is the correct size for one boat and 17 staff members harvesting 1 000t/year. We may increase to 1 200t/year”.

Email [email protected] for further information.