Pasteurellosis in cattle can assume several forms. Pneumonic (lung) pasteurellosis is mainly a problem in feedlot cattle. Under intensive conditions such as dairies and bull-testing stations, other cattle and calves may be affected. In dairy cows and calves, stress conditions readily cause mortality.

The bacteria Mannheimia (Pasteurella) haemolytica plays a leading role in the development of bovine respiratory disease (BRD), a condition also known as shipping fever. The bacteria Pasteurella multocida is also implicated. In South Africa, cattle are normally affected by P. multocida types A and D. Haemorrhagic (bloody) septicaemia caused by P. multocida type B and E is largely unknown in South Africa, although it does occur in the rest of Africa, especially wet and hot tropical regions.

All breeds, ages, and sexes in cattle are susceptable. Cattle have the smallest internal lung surface area per body weight of all mammals and lack the ability to compensate should a part of the lung be infected. For this reason, cattle easily die from pneumonia. Feedlot cattle are most susceptible to pneumonic pasteurellosis as they are continually subjected to high stress levels. Bacteria are easily transferred should an infected animal cough or sneeze, releasing a spray of droplets that other animals take in by breathing.

Transporting weaners and adult cattle, especially over distances exceeding 100km, is the most potent stress factor predisposing cattle to pneumonic pasteurellosis. It leads to serious dehydration, electrolyte disturbance and rumen malfunction.

Other stress factors predisposing the development of pneumonic pasteurellosis are dust, especially under windy conditions, noxious gasses (ammonia and carbon monoxide), a carbohydrate-rich diet, excessive day and night temperature differences, exhaustion, hunger, weaning shock, overcrowding, recombination or disturbance of social hierarchy, vaccination and dehorning.

Disease development

Pasteurellosis is usually preceded by para-influenza type 3 (PI3), contagious bovine tracheitis (IBR), bovine viral diarrhoea (BVD), bovine herpes virus type 1 or respiratory syncytial virus (BRSV); an inflammation of the respiratory passage that initially causes lung lesions and suppresses immunity. The bacteria Histophilus somni is also involved in such infections.

Other micro-organisms, such as Mycoplasma bovis, may play a role in lung and joint infection, especially in younger cattle and calves. Sick animals do not react favourably to antibiotic treatment. Infection with Chlamydia bacteria may also play a role in pneumonia in cattle, although their role is still uncertain. Synergism (cooperation) between Chlamydophila and M. haemolytica bacteria is possibly involved.

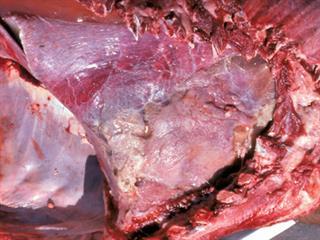

Bacteria such as Trueperella (Corynebacterium, Arcanobacterium) pyogenes and Pseudomonas usually occur secondarily in lung lesions, causing chronic abscesses in the lungs.

Weaning calves

Pneumonic pasteurellosis peaks in autumn and winter, especially after cold and windy days. This period coincides with the traditional weaning period in beef cattle. Weaning shock combined with transport predisposes especially younger calves, which are not yet adapted to cold, to pneumonia.

Feedlot cattle

In this environment cattle may become sick at any time, but mostly within 45 days of being admitted. The first cases may be recorded from the fourth day onwards, with the peak between day 14 and day 21. Up to 10% of feedlot cattle may become sick, with up to 50% in exceptional cases.

Dairy calves

The prevalence of the disease in intensively reared dairy calves is between 1% and 3%, with mortality below 1%. Incorrect accommodation, poor ventilation, mixing of weaners of different ages and poor hygiene contribute to an outbreak. Unlike feedlot cattle, which are usually subject to several simultaneous diseases, dairy calves usually contract one disease. This is usually easier to treat and control. Normally the mortality rate is less than 1%, although rates of between 4% and 20% are on record. Great economic losses due to retarded growth and weight gain occur.

Disease signs

Festering pneumonia and abscesses develop. The disease can spread, leading to pericardial infection, meningitis and joint infection. Peritonitis and pleuritis may also develop. Other disease symptoms include fever, depressed appetite, nasal discharge, red nose with sores and crusting, sensitivity to light, swollen eyelids, eye infection, depression, rapid and laboured breathing, coughing fits, extended head and neck, laterally rotated elbows, and breathing through an open mouth with projecting tongue. Weight loss is dramatic and diarrhoea may occur. Dairy cows suffer reduced milk production and may abort.

Prevention and management

- Timeous antibiotic and supporting treatment of sick animals;

- Good care and feeding of sick animals;

- Prevention and elimination of stress factors that predispose animals to pneumonic pasteurellosis;

- Vaccinate calves before dehorning, weaning or dosing them against internal parasites;

- Vaccinate against M. haemolytica and virus diseases like PI3, BVD and IBR;

- Feedlots must preferably buy weaners directly from their farm of origin, already vaccinated against M. haemolytica and other bacterial and virus diseases, dosed against internal parasites and fitted with identifying ear tags. The farm of origin should be free of Trueperella abscesses and BVD infection;

- Weaners or feedlot cattle of similar size, type and sex must be put in a kraal. Apart from the initial processing on the day of arrival, weaners should not be handled before 21 days after arrival at the feedlot. Molasses and water must be mixed in with dry ration to avoid dust. Adding silage to the ration will keep it moist;

- Control dust by providing sprinklers;

- Consult a vet.

Vaccination

The control of respiratory diseases caused by pasteurellosis has become more effective during the past few years due to improved vaccines that have been developed for cattle. Simple toxoid (inactivated pathogen) vaccines against

P. multocida protect cattle well. The only vaccine available in South Africa containing P. multocida is the Onderstepoort Biological Products Pasteurella vaccine for cattle (G 0478). It contains types A, D and E, as well as M. haemolytica type A.

The Pasteurella group bacteria secrete a harmful leukotoxin factor, which destroys white blood cells (leukocytes). M. haemolytica type A1 is the only type important for cattle in SA. A vaccine against this bacterial leucotoxin has been developed and is being manufactured. These vaccines include Bovitect P (G3002), Bovitect P1 (G3001), Bovitect III (G3211), Bovivax (G2744), Leukopast (G2395), One Shot Ultra 7 (G2818), Respiravax (G3867), Pyramid 4 + Presponse SQ (G2822) and Pastvac (G1511). Triangle 4 (G2308) contains M. haemolytica A1 bacteria (inactivated bacterial vaccine).

Leukotoxin vaccines offer no protection from P. multocida infection. They are normally administered in two doses, three to four weeks apart. In feedlots, this period may under some circumstances be 10 to 14 days. Bacteria of the Pasteurella group normally occur in small numbers in the mucous membranes of cattle. Vaccines with a leukotoxin basis protect cattle well against practically all M. haemolytica infections.

Contact a vet about vaccinating and treating cattle.

Email Dr Jan du Preez, managing director of the Institute for Dairy Technology, at [email protected], or Dr Faffa Malan, manager of the Ruminant Veterinary Association of SA, at [email protected].