Liver fluke occurs widely in cattle herds in North West. This has been shown by analysing blood samples in Vryburg, Ottosdal and Potchestroom. About 75% of the trial herds tested positive while nearly 80% of the animals in the trial herds were infected.

Dr Ferreira says liver fluke is also increasingly found in the Kalahari and Namibia. “Common liver fluke (Fasciola hepatica) traditionally occurred in the cooler and wetter eastern parts of the country while giant liver fluke (Fasciola gigantica) occurred in the warmer and drier western parts of the country.”

Liver damage

The parasites destroy liver tissue and cause thickening of the bile duct, causing it to become blocked and infected, impacting on liver function and bile secretion. The most damage is caused by the immature liver fluke on its migration from the intestinal tract to the liver and the cystic duct.

Dr Ferreira says this damage leads to reduced glucose and protein synthesis. “Growth and development as well as milk production and feed conversion ratio are impaired. Weakened cholesterol production retards ovarian activity, affects conception and impacts on intercalving periods,” he adds.

A damaged liver limits an animal’s ability to store trace minerals, lowering its immune system. This is evident in increased problems with foot rot and a high somatic cell count in infected cattle. Infected cattle are more susceptible to pathogens that can lead to an increased incidence of clostridia and salmonella infections. Liver fluke limits the effective absorbtion of vitamins A and E. The loss of plasma protein and blood caused by liver damage can cause anaemia and, in severe cases, death.

Water and the intermediary host

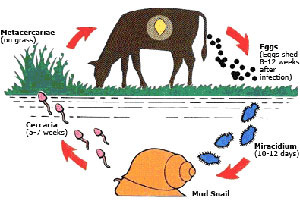

Open stretches of slow flowing or standing water such as wetlands and puddles formed by leaking water troughs inhabited by the flukes’ freshwater snail host species form the ideal habitat for liver fluke, says Dr Ferreira. “The mature fluke in the bile duct lays its eggs in the liver of an infected animal. The eggs leave the body via the small intestine and end up in the animal’s dung in the water or wet parts of the veld. In ideal circumstances (higher than 26° C) the first stage larvae, known as miracidia, can hatch in 10 to 12 days.

Liver fluke life cycle

The freshwater snail Lymnaea sp. is the intermediary host and first stage liver fluke larvae (called miracidia) can infect it within 30 hours. Larvae multiply inside the snail and leave it as cercariae, which attach themselves to grass stalks and encyst to form the infectious stage, known as the metacercariae, which animals ingest as they graze.

The metacercaria bores through the gut into the liver where it develops to the mature fluke in the bile duct. The adult parasite lays eggs and these pass through the bile duct to the intestine to be voided in the dung. During dry periods, the freshwater snail host submerges itself in mud. Cercariae are released as soon as wet weather starts.

Animals tend to congregate around water points, especially during drought, increasing the possibility of infection. Each miracidium that enters a freshwater snail can multiply to 300 cercariae, encysting to form metacercariae. “Infections are most prevalent during autumn and spring because of the change in temperature,” he cautions.

Avoid blanket treatment

Dr Ferreira warns against blanket dosing of herds, stressing that the farmer must confirm that an animal is infested with liver fluke before treating it. Clinical symptoms include deteriorating condition, poor reproductive performance, impaired growth and a weakened immune system. Liver fluke can be detected through blood tests.

Environmental management in conjunction with pharmaceutical control is the most effective way to manage for fluke and prevent infestation. Fence off wetlands and stretches of open water where possible. Repair leaking water troughs and eliminate standing water to minimise habitat for snail host species.

“No chemical product is 100% effective against all the stages of the liver fluke,” Dr Ferreira concludes. “Nothing that will exterminate the parasites during the migratory stage from the intestinal tract to the liver is available. The active ingredients in different chemical products are all aimed at the separate development stages.”

He advises cattlemen to contact their local vets or animal health consultants on product use. “Make sure you use a product that works, especially in terms of controlling the parasites in the early immature stage. Products containing both triclabendazole and oxsfendazole are particularly effective. The ELISA blood test is the most effective way to determine infestations older than 14 days.”

Contact Dr Ferreira [email protected]