Charlie Crowther is the first to confess that his extreme approach to farming with pasture-reared pigs is aimed strictly at a small niche market. In addition, he has been at it for only four years, so is not yet sure if his approach is sustainable in the long term. But he is committed to making it work because, by his own admission, this is the only way that he will ever farm with pigs.

Demand meets supply

Crowther grew up on a farm near Stellenbosch and after school spent several years working on livestock farms in the UK, Australia and New Zealand. He returned in 1993 to work on the 300ha Glen Oakes in the Hemel-en-Aarde valley between Caledon and Hermanus, and bought the farm at the end of 1994.“There wasn’t much on the farm. The idea initially was to plant apples, but my real passion has always been for livestock,” he recalls.

Charlie Crowther

“Then about four years ago a friend of mine who ran a deli in Hermanus started making his own deli meats, such as parma ham, proscuitto, pancetta and salami. “He said he needed pork from pigs reared in as natural a setting as possible, that was hormone- and stimulant- free, and that wasn’t raised on a diet containing animal by-products.”

And with that the deal was sealed – as this was exactly the kind of product that Crowther was keen to provide.

Getting started

“I always said that if I ever farmed with pigs I wanted to do it in a natural, wholesome way, but I realised that because of the costs involved with rearing pigs like this, I would need a niche market, someone prepared to pay a premium to cover the high input costs. So when the deli opportunity came along it wasn’t difficult to accept the challenge,” says Crowther.

He started with only a handful of pigs to see if the idea of pasture-reared pigs would work, and soon realised there was more to the undertaking than he had first appreciated. “You have to learn to think like a pig,” he laughs. Fences present an ongoing challenge, and the sheer determination of pigs to break through fences can prove tiresome. “The pigs are impossible! They break down fences as fast as I can mend them and sometimes I feel as if all I ever do is fix fences so that the pigs can break them down again,” he says in mock-exasperation.

Paddocks, Feed and water

Crowther farms with about 300 pigs that are kept mainly on 30ha of irrigated pastures. Foraging and wetland areas also form part of the paddocks, and he grows 30ha of dryland pastures. The pigs are kept in small groups according to their size and gender. “I don’t castrate the males so they have to be kept separate from the females,” he says. The paddocks range from 1ha to 4ha and the groups are rotated as needed on two or three paddocks.

Pigs at the feeding buckets. They are fed three times a week, but Crowther has not yet found the ideal amount of feed per pig.

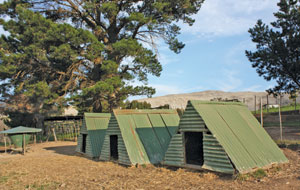

Apart from providing sufficient pasture, the paddocks also have water troughs, huts for shelter, trees for shade, and either wallowing holes or access to the stream that borders the front of the property. “I basically followed my instincts when deciding what to plant as grazing and chose a mix of lucerne and clover. Under normal circumstances, these pastures would probably need to be replanted every five years, but the pigs do a lot of damage as they graze and forage and I’ve had to replant the pastures more often.”

The pigs are also given a professionally balanced ration consisting of locally sourced barley, soya bean oilcake and canola oilcake. “We feed them three times a week to encourage moderate weight gain but I’ve not yet established the ideal quantity,” says Crowther. He strongly believes that the pigs’ diet makes a significant difference to the quality of the pork, and to add extra flavour, he feeds acorns to the animals during the six weeks prior to slaughter.

Breeding

The quality of the meat is not due solely to a varied and natural diet, however; it also comes from careful breeding. “All the breeding animals are bought in from Sweetwell farm in Somerset West. They currently consist of 30 Landrace-Large White mixed breed, breeding sows, and three Red Duroc boars. This is the ideal mix for the type of pork we want: with Duroc boars we get well-marbled meat while the Landrace-Large White mixed breed sows have excellent maternal characteristics,” says Crowther.

Special houses for the sows and piglets. The sloping roofs allow the piglets to move to safety in the low corners should their mother roll onto them by mistake while sleeping.

According to the farm’s mating programme, the sows have two litters per year. “I haven’t had to replace any of the sows yet and some are now having their sixth litter. The average litter size is 10 to 12 piglets,” says Crowther. He keeps careful track of the breeding animals and about two days before they are due, brings the sows in from the field to give birth in the special farrowing huts.

The sows and piglets are kept in smaller pastures near the farrowing huts for about two weeks before being moved to paddocks where they remain together until the piglets are weaned at six weeks. The piglets are dewormed at weaning, grouped according to size and sex and then moved to paddocks. From this point, they are left to forage, play and wallow in the mud, and simply fed their ration three times weekly.

Marketing

Crowther markets his pigs when they are between 10 months and 12 months old and at a carcass weight of 80kg to 100kg. He sells 25 to 30 per month, which are slaughtered at registered abattoirs nearby. “Everything we do takes twice as long as on a commercial farm. It can take me half a day just to wean one litter of piglets. I’m not convinced that farming with pigs in this way will be feasible on a large scale without access to a niche market,” he says.

Despite these reservations, Crowther is adamant that this is the only way he will ever farm with pigs. He refuses, however, to call his pigs free-range or organically reared. “We go beyond free-range. Commercial free-range is, in my opinion, the equivalent of an outdoor feedlot and I’m not prepared to rear pigs in a system that resembles a feedlot in any way,” he says.

Limitations

The advantages – and ironically, the limitations – of the irrigation system and landscape on Glen Oakes also play a part in the success of Crowther’s enterprise. “Our water comes from the farm dam and is gravity-fed by mountain streams. I rely solely on gravity to carry the water from the dam to the sprinkler systems that irrigate the 30ha of pastures and this is one reason I can afford to farm with pigs on pastures – I don’t have any electricity costs for irrigation.”

A disadvantage of the farm’s layout, however, is that the land available for irrigation is limited, preventing Crowther from expanding. This is somewhat frustrating, as the market appears to be bigger than what he can supply. Crowther’s friend at the deli has since begun to dedicate most of his time to making high quality charcuterie, mainly using pork from Glen Oakes, which is in high demand.

Crowther explains that while there is a fair amount of interest in pigs reared in this manner, up until now few people have been willing to pay a premium for the product as they fail to appreciate the high cost of rearing pigs on pasture.

An optimal environment

What also plays a major role is the fact that this farm provides the perfect natural setting for pigs,” he says. “The farm offers them plenty of shade and wallowing holes. You cannot farm like this in an area where pigs will be exposed to the sun all day because they’ll suffer heat stress and sunburn.” Despite these advantages, Crowther admits that he is still feeling his way with the pasture-fed approach.

“I’m still in a learning curve and am continually making changes that will help bring down input costs. I’m optimistic about the business, but time will tell.”

Email Charlie Crowther on [email protected]