“Nobody thought I would get it off the ground,” says Elmarie van Aswegen about her efforts to milk ewes and produce sheep cheese in the southern Free State. “Imagine a woman telling traditional farmers that they could milk their sheep.”

But Elmarie was determined, and in the late 1990s succeeded in breeding South Africa’s first milk sheep – recognised by SA Stud Book as the SA Milk Sheep.

She went on to produce award-winning cheese – and says that she is far from done yet.

Last year, Elmarie imported three Awassi rams from Australia. This is a Middle Eastern breed known for its hardiness and exceptional milk production. “I’m like a Jack Russell terrier that doesn’t use logic but just walks the talk,” she quips.

The beginnings

It took Elmarie only a day to decide to take a package from the Western Cape Provincial Administration and go home to farm with her father, Pieter. Although she never thought she would be the next Van Aswegen to return to the farm, she admits that she has always been a farm girl at heart. Before relocating, Elmarie got in touch with Joan Berning of Finest Kind in Plettenberg Bay and enrolled for a cheesemaking course in early March 1997.

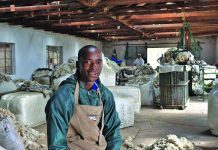

Elmarie van Aswegen

Joan suggested that she focus on milking sheep and producing niche market cheeses. She liked the idea, but when she arrived home in March 1997 and did some research, she found that the sheep milk industry in South Africa was practically non-existent. Sourcing milk sheep breeding stock in South Africa and abroad was nearly impossible.

Keith Ramsay, then the Registrar for Livestock Improvement in Pretoria, told her that if she were willing to compile a biological impact study (BIC) and use imported East Friesian milk sheep semen in a research project recognised by a tertiary institution, her request could be considered. Undaunted, she set out to do exactly this. Assisted by Prof Johan Greyling of the Faculty of Natural and Agricultural Sciences at the University of the Free State, Elmarie completed the BIC and registered for a Master’s degree in Sustainable Agriculture on the subject of milk sheep.

“It was my destiny,” she says simply. “I had to do it.” Her research focused on the development of the SA Milk Sheep in a breeding programme that included three ewe groups: 50 Blinkhaar Ronderib Afrikaner, 50 Afrino and 50 Merino Landsheep, all of which would be inseminated with 150 straws of East Friesian semen sourced from New Zealand in 1998.

By February 1999, the ewes had been acquired, and by October 1999 the first East Friesian sired lambs were born on Patria. In 2001, Elmarie began milking the new SA Milk Sheep ewes and producing sheep’s milk cheese in a processing facility established with a loan from the government’s small business finance agency Khula.

New genetics

But there were problems with the new SA Milk Sheep. The East Friesian-type sheep could not deal with the heat in the area, and blistering sun resulted in cancer on the eyelids and ears.“The East Friesian has poor pigmentation and its ears have no hair – the wool starts behind the ears,” she says. “I had to look at alternative genetics to introduce hardiness and pigmentation.”

In 2003, she decided to investigate importing Awassi sheep, farmed in significant numbers in the Western Australian Outback by affluent Middle Eastern businessmen. From the University of Western Australia she established that the Awassi sheep in Western Australia were of the traditional mutton line, from which an improved Awassi dairy strain had been developed in Israel.

Elmarie travelled to Perth to source Awassi genetics via an Australian import/export company that managed the sheep for the foreign businessmen. “The export company was based in a tower building in the middle of Perth,” she recalls. “The members literally laughed in my face when I told them I was there to talk about the Awassi.”

She was told that it was nearly impossible to source Awassi genetics and due to the Iraq war they could not contact businessmen who might be willing to negotiate. Disappointed, Elmarie went home empty-handed. But two weeks later, she received a message that there were in fact some Awassis available. The problem was that the ewes were priced at R22 000 each before the added transport cost from Australia to the Free State. She was forced to turn down the offer.

In 2006, she flew to Europe to try to convince the unwilling French to supply her with semen from the Lacaune milk sheep, a breed that virtually defines the thriving French milk sheep industry. She toured farms and factories in France (including those in the Roquefort-sur-Soulzon commune, famous for its Roquefort sheep milk cheese), Portugal and Spain and eventually talked the French into selling her the Lacaune semen.

This time, however, the SA Registrar of Animal Improvement refused to allow the import. It was a devastating blow for Elmarie. “We’d convinced the French to make a special arrangement,” she recalls. “The problem was always in Pretoria where the registrar is based.”

Success at last

In 2003, Elmarie located a flock of improved dairy Awassi sheep in Eastern Australia, but could not arrange a sale with their Australian owner. In late 2010, she learnt that the sheep would be auctioned, so she found an Australian agent and transferred the necessary funds. However the auction was unexpectedly cancelled, a reflection of the politics surrounding the sale of Awassi genetics in Australia.

Ovis Angelica Divine Sheep’s Cheese

Finally, a year later, her agent told her that a handful of Awassis would at last be made available to her, and she jumped at the opportunity. “At the end of the day, I was able to buy only three rams – it was just too expensive and difficult to get anything else,” she recalls. “Two rams were old, but I insisted on one young ram.” The price of the young ram alone – the most expensive of the three – was A$15 000 (R143 000), while export, import and transport costs increased Elmarie’s total bill significantly.

On 19 March 2012, the Awassi rams arrived and were checked into the Gauteng quarantine station at OR Tambo International Airport. There they stayed for a month, under the watchful eye of a delighted Elmarie. From the quarantine station, the rams were taken via Ramsem in Bloemfontein – where their semen was collected and frozen – to Patria.

Since then, they have been kept in the ram shed on Patria and have sired two batches of first-generation Awassi-type lambs, one step closer to Elmarie’s dream of breeding pure Awassis, a goal which should be achieved within six generations. She also hopes to bring in Awassi embryos from Australia to boost her new milk sheep breeding programme.

Change of direction

“My main focus is no longer on the cheese. I have a long-term goal of breeding pure Awassis,” she says. “I’m also going to gear myself to export genetics.” Elmarie admits to concerns about export problems due to foot-and-mouth disease in South Africa. “The minister of agriculture isn’t sorting it out,” she says.

She has already had requests for Awassi genetics from South Africans and people in other African countries, including Kenya and Mozambique. And ironically, she sees Australia as one of her best markets. “I already have Australians that want to buy embryos from me,” she explains. “The rams hadn’t even landed when the Australians phoned me, because they can’t get hold of Awassi genetics there.”

Phone Elmarie van Aswegen on 051 713 7091 or mail her at [email protected]. Visit www.sasheepdairy.co.za.

Other sources: www.culturecheesemag.com, www.fao.org, www.agro-tour.co.il and www.sheepcentre.co.uk.