The fungus appeared only when I planted a new variety. I’m not sure of the reasons, but it seems as if some cabbage varieties are more susceptible to this disease. Different species of the fungus occur in different crops, but the one to watch out for is Sclerotinia sclerotiorum as it can attack a number of crops. Sclerotinia is also called white mould, from the cottony white fungus that appears on infected plants.

Sclerotinia life cycle

The life cycle of the fungus is interesting. Dark, flattened, hard objects called sclerotia form within the white mould. Resembling mouse droppings, they develop at an advanced stage of infection and can easily be missed unless you look for them. The sclerotia remain in the soil with the crop residue thoughout winter. After winter, they germinate in cool, rainy weather to produce tiny, light-brown mushrooms called apothecia.

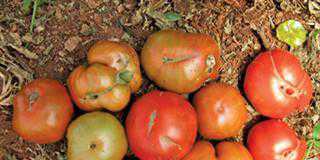

This is the type of weather that favours the growth of wild mushrooms (the temperature is usually 15°C to 25°C). When this is followed by dry, warmer conditions, clouds of spores leave these mushrooms and can drift quite far in the wind. In beans, infestation often starts among dead flowers, but with cabbage, I find it usually starts where the outer leaves and the head merge. Moisture tends to get trapped in this section, providing the ideal conditions for the spores to germinate and invade the plant tissue. The white fungus spreads from here to cover the entire head, and the tissue becomes watery and rotten.

Look for those lumps

You will not initially find the sclerotia but with careful observation, you will see lumps starting to develop in the fungus mass which later become dark and hard. At this stage, only one or two plants may be infected, and it’s easy to think that this is nothing to worry about. In fact, farmers often ask me to look at such cabbages more out of curiosity than alarm.

The problem is that the sclerotia may become the source of a much more serious infestation the following year. Millions of spores may then develop from infected plants. I once came across a farmer who had bought a farm where sunflowers had been grown. In the case of sunflowers, Sclerotinia attacks the root system. The new owner’s cabbages were badly damaged due to the high concentration of spores left over from the sunflowers.

Infestation control

If there are only a few infected cabbages in the land, remove each plant entirely and bury it 30cm deep outside the land. The little effort involved is well worth it. If you have a fairly high level of infestation, it becomes impractical to remove all infected plants by hand and bury them. In this case, it is better to follow a rotation system that excludes host crops for the next season.

In some cases, especially when the soil has a high organic content with plenty of soil organisms, certain species of fungi attack the sclerotia and use them as a source of food.

Prevention the only answer

Using chemicals is not always a solution, because by the time you become aware of the disease it is too late to take action.

If, however, you believe that there is a likelihood of infection, use a fungicide such as Sumisclex or Rovral as a preventative measure. The disease is usually worse in spring when the temperatures favour germination. Use a spray while these conditions prevail.