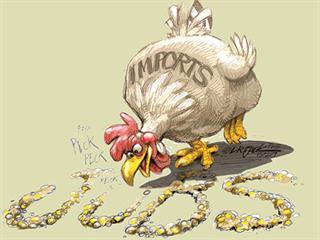

The South African poultry industry has been in the news in recent years, and much concern has been expressed about the struggle against foreign imports. A number of trade applications have been submitted and challenged by meat importers, whose argument seems believable: imported chicken is cheap, and cheap is good.

Although at face value, imports are cheap, in the long run they are extremely costly for our country, economy and people. South Africa has high levels of unemployment, and anyone who thinks that cheap is good is missing the point. Importing 10 000t of chicken and chicken products costs about 1 000 direct and indirect jobs. Without a job, what can you afford? A fair price for local goods means a decent life for all, and imports will never provide this.

People should be able to eat as much as they desire. Although the developed world makes up only 13% of the global population, this 13% effectively controls the diets and food production of the remaining 87%. Why is this so, especially considering that those in the developed world are eating more than enough?

Space to grow

The developed world has been able to produce surpluses for a long time, and has found it politically appropriate to support excess production in various ways. As part of the developing world, South Africa is still trying to grow its food-producing industries to support the needs of its people. Various other developing countries are further behind us, and all of us need space to grow our industries if we are to secure food for our populations. Without a chance to grow, we become dependent on the largesse of others.

Much criticism is levelled at the EU for its Common Agricultural Policy (CAP). It is often forgotten, however, that many people suffered starvation in Europe after the Second World War, and CAP grew out of a response to remedy this. Arguably, though, CAP has been too successful. The Great Depression in the USA led to a similar plan. The trouble is, once the taps are switched on, they are difficult to switch off.

When you are dealing with grains of any kind, food security requires that you plan to produce more than you need, as changing weather and climate conditions make it unlikely that there will always be enough to harvest. And if too much is produced, there must be a market for the produce.

In a just world, those who have too much can meet the needs of those who have too little, so producing more than you need is not in itself bad. The problem lies in quantity and method.

No competition

The USA plans its grain output so that it produces much more than it needs to cover weather variables; in fact, it plans to produce surplus for export. For this to work for the rest of the world, fair prices are necessary. You cannot afford to grow maize in Mozambique if it’s artificially cheaper to produce maize in the USA. Every US grain producer receives various forms of production support, and with an insurance scheme guaranteeing that he will never make a loss, why should he worry if he produces too much? The Mozambican farmer simply cannot compete, regardless of his competence. Free and fair trade? Hardly.

Dumping jobs

The problem with imported chicken is simple. It costs a specific amount to produce a slaughtered whole bird, and this bird is used as raw material to produce chicken portions. These portions should cost more – kilogram for kilogram – than the whole bird, as there is extra work to be done, not to mention cutting losses. The trouble, though, is that the dark meat portions don’t cost more.

Consumers in the developed world prefer white breast meat. So huge surpluses of dark meat pile up in warehouses, and these are then sold to the developing world at way below the cost of production. Without a doubt, this is dumping. Thus, the dietary habits of the developed world and its preference for white meat are exported to us, and jobs are lost here.

We urge consumers to buy local and fund a local job. Let Europe and the USA leave their surpluses and wastes in their own countries, and let us make space for the developing world to feed itself. South Africa needs opportunity and growth. It needs to feed itself sustainably over the long-term. And it needs to build our food security – independent of foreign imports. What we don’t need is charity, because it comes at a price that’s not worth paying.

Phone Kevin Lovell on 0861 768 5879 or 011 795 9920, or email [email protected].