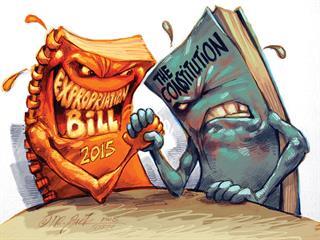

The Expropriation Bill is back, and it is just as unconstitutional as its predecessors of 2008 and 2013. It still gives the State the power to take ownership and possession of property by notice to the owner – and without a prior court order confirming the validity of the expropriation.

It also puts great pressure on expropriated owners to accept whatever compensation the State might offer; this time by saying they will be deemed to have accepted these amounts unless they sue for more within two months. Overall, the bill is a draconian measure that makes it quick and cheap for all state entities to take from farmers, miners, firms and ordinary people their most important assets – often their sole assets – built up over a lifetime of endeavour.

The revised Bill

As before, the bill seeks to allow any “expropriating authority” to take property by serving a notice of expropriation on the owner. Ownership of the property in question will then pass automatically to the State on the “date of expropriation” identified in the notice, which could be the day after the notice of expropriation is served.

Like its predecessors, the bill empowers the State to take property upfront, by notice of expropriation to the owner, and leaves it to those affected to seek redress in the courts thereafter – if they can afford to. However, ‘self-help’ of this kind is barred by both the common law and the Constitution.

Under the common law, the State cannot simply seize property – even a gun likely to have been used in committing a murder – without first obtaining a court order in the form of a search-and-seizure warrant. This common law protection for property rights has since been buttressed by the 1996 Constitution, which lays down a number of requirements for a valid expropriation. The Constitution also prevents people from being evicted from their homes without express judicial authority and, in many instances, the provision of suitable alternative accommodation.

Key features

According to the bill, “property is not limited to land and includes a right in such property”. This definition is wide enough to include movable property, along with mining rights, servitudes, patent rights, and shares in companies. The bill extends the power of expropriation to any “expropriating authority”. Included among such authorities are all “organs of state”, along with any other person “empowered to … expropriate” by the bill itself or “any other legislation”.

The bill allows expropriation not only “for public purposes” but also “in the public interest”. Though this wording is in keeping with the property clause, the bill’s definition of “the public interest” goes beyond what the Constitution says. According to the Constitution, “the public interest includes the nation’s commitment to land reform, and to reforms to bring about equitable access to South Africa’s natural resources”.

The bill starts by echoing this wording, but then adds that the public interest “includes other related reforms in order to redress the results of past racial discriminatory laws or practices”. Hence, whereas the Constitution permits the expropriation of land and other natural resources, the bill seeks to allow it in much wider circumstances.

Ramifications

The bill seeks to empower all organs of state to expropriate land and other property wherever this is necessary, in their view, to “redress the results of past racial discriminatory laws”. Expropriated owners will be under great pressure to accept the compensation offered by the State, which will generally be less than market value. Damages for consequential loss will no longer be payable, even though expropriation is a drastic measure which places an inordinately heavy burden of redress for past societal wrongs on the shoulders of particular individuals.

If justice is to be done to those affected, the full extent of their consequential losses needs to be taken into account, not disregarded. Instead, the bill makes it possible for the State to acquire all manner of assets at bargain basement prices and irrespective of the great hardship this may cause.

In addition, although ownership and possession may pass very swiftly to the State after the notice of expropriation has been served, payment of the compensation due could often be delayed. Banks holding mortgages over property that is expropriated will also be at risk, as the compensation payable may not be enough to pay off outstanding loans.

The government claims that the bill is needed to speed up land reform, but this is a tired and unconvincing excuse that brushes over many inconvenient truths. In fact, only 8% of South Africans want land to farm; at least 73% of land reform projects have failed, and the government has already spent billions of rands on taking hundreds of farms out of production with little benefit to anyone. Such pointless waste must stop, not be given further impetus.

Public works minister Thulas Nxesi now adds that the Expropriation Bill is needed to speed up the infrastructure programme. But this has stalled because of other policy mistakes, including a quota-driven affirmative action policy that has left many state entities without the experience to manage large projects. However, in putting forward this flawed rationale, Nxesi implicitly acknowledges that the Expropriation Bill will by no means be confined to farmland. Many people outside the agricultural sector have long-tended to believe that the bill would not affect them, but this is an illusion. Others may think that the risk of expropriation applies solely to white South Africans, but this too is a fallacy.

Expropriation and the NDR

The government is not really seeking to cure the unconstitutionality of the current Expropriation Act of 1975 (the Act), for every version of the Expropriation Bill it has put forward since 2008 has been just as unconstitutional as the 1975 statute. Nor is government’s true aim to speed up land reform or the provision of new infrastructure. The real aim of the ruling tripartite alliance – the ANC, Cosatu and the SA Communist Party – is to use expropriation to advance the national democratic revolution (NDR) in this second and more radical phase.

Presently the agricultural sector is the most at risk, but the threat to property rights is unlikely to stop there. And property rights matter. The tripartite alliance wants to remove them as they limit State power. That is also why these rights need to be respected. Property rights should not be made subject to a bill that is not only unconstitutional but also makes it quick and cheap for all organs of state to take ownership of more private property.

The more this process unfolds, the more South Africans of every race will be disempowered and left dependent on an increasingly callous and overbearing State. This is an excerpt of an article by Dr Anthea Jeffery, head of policy research at the IRR.

The full article is available here: The expropriation bill is back and its still unconstitutional.

Email Dr Jeffery at [email protected].