Stress is defined as an external influence on the balance (homeostasis) of a system, which at any moment can produce a negative reaction.

Homeostasis maintains the stability of the body’s internal environment in response to external change. On a very

hot day, for example, the animal stays in the shade, drinks more water and eats less.

This behaviour, called ‘thermoregulation’, reduces stress.

Thermoregulation is easier on hot days than during cold spells, which is why stress-related diseases are more common during the transition from autumn to winter.

The dangers of poor handling

Recent research shows that an animal cannot maintain homeostasis properly even during routine handling. In other words, it suffers stress.

There may be no obvious signs of this, but the animal is certainly more susceptible to stress-related diseases such as coccidiosis and pasteurellosis.

When an animal (or human) is stressed, it releases the steroid hormone cortisol to supply energy in the form of glucose that enables it to escape from the stressor such as by running away. In the short term, the animal benefits from this cortisol release; in the long term, however, it suffers negative consequences.

Too much cortisol released due to this constant stress can impair reproduction, while a compromised immune system increases the animal’s susceptibility to disease.

The mechanism of the immune-suppressive effect of stress is still uncertain, but stressed animals have a less effective response to pathogens than unstressed animals.

This is frequently seen in the livestock industry, which relies mainly on vaccines to prevent disease. A farmer will often say that a vaccine is not working properly, when in fact an animal with a high concentration of circulating cortisol cannot mount an efficient immune response.

The important stress-related diseases

Diseases typically associated with stress are pasteurellosis, Mannheimia haemolytica, and coccidiosis. Most of these pathogens are opportunistic organisms that occur naturally in livestock, but kept under control by the immune system.

Immunity develops either through vaccination or through continuous exposure to a low and non-fatal level of infection. But stress (from a high cortisol level) can lower this immunity to such an extent that the animal contracts the disease.

Pasteurellosis and Mannheimia haemolytica

An important disease that develops as a result of stress is lung infection caused by Pasteurella multocida or Mannheimia haemolytica. Pasteurellosis is an important cause of economic loss in the livestock industry. It is often encountered in feedlots and bull testing centres around the country after the seasonal change from warm to cold weather.

It is more common in young growing cattle, particularly weaners transferred to a feedlot. P. multocida causes a form of broncho-pneumonia, while M. haemolytica causes a form of pneumonia.

Symptoms of these diseases include morbidity and anorexia due to fever, coughing and a nasal discharge. A stethoscope reveals abnormal lung sounds, and the animal tends to breathe faster than a healthy animal due to impaired lung function.

The initial diagnosis can be based on the history of the case and on the response to treatment, and can be confirmed by sending nasal swabs to a laboratory. Antibiotic treatment – the sooner the better – will increase the chance of survival.

To control the disease, it is crucial to minimise stress. Vaccinate animals well in advance of expected adverse weather and train all stockmen in proper handling procedures.

Coccidiosis

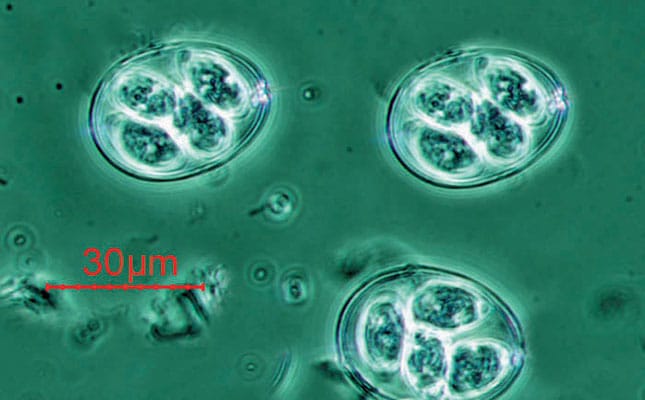

Coccidiosis in cattle is caused by Eimeria parasites and is common in young animals moved from pasture to feedlot. Although it has a low fatality rate, recovering animals often exhibit poor production. Symptoms include diarrhoea with or without blood and mucous, dehydration, emaciation and malaise.

Diagnosis is based mainly on the case history, confirmed by dung analysis

As the disease is transmitted via the faecal-oral route, all animals in the group should be treated with coccidiostats (sulphanomides; sulphadimidines; diclazurils). This is particularly important under unhygienic conditions.

Administer electrolytes to affected animals to prevent dehydration and replace minerals.

NOTE: The above is a brief overview of stress-related diseases. For more information, contact your veterinarian or animal health technician.

Source: Kruger, L: ‘The effect of environmental factors on stress in cattle.’ (ARC Animal Production Institute, Newsletter No 103).