There are currently between 150 and 200 elephants in the Kamanjab, Khorixas and Otjikondo commercial farming regions of Namibia.

Elephants also occur sporadically in the Ugab Valley and the Kalkfeldt district, where lone bulls cause considerable damage to farming infrastructure by destroying fences, damaging kraals and stockades, and overturning windmills.

The daily food and water intake of a single elephant is the same as that of about 30 head of cattle, which means the current elephant population in the commercial farming areas is equivalent to 6 000 head of cattle.

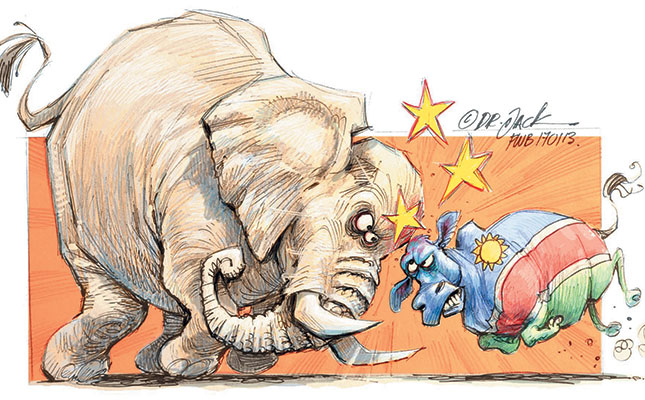

Given the drought experienced in our country over the past four years, it goes without saying that this competition for food and water between livestock and elephants has had a terrible impact on the long-term sustainability and profitability of livestock production.

Indications are that a minimum of five herds, which include family and breeding groups led by matriarchs, currently roam the area. The breeding groups are a particular problem as they often include young calves that cannot reach water inside a reservoir.

Cows then simply tear down the reservoir walls or puncture water tanks with their tusks. The elephants have also learnt to topple windmills and pull up submersible pumps to gain access to water. The matriarchal groups on the other hand are relatively territorial and generally keep to their respective areas.

Cows then simply tear down the reservoir walls or puncture water tanks with their tusks. The elephants have also learnt to topple windmills and pull up submersible pumps to gain access to water. The matriarchal groups on the other hand are relatively territorial and generally keep to their respective areas.

The so-called bachelor bull herds are especially destructive. These animals often seem to cause damage on purpose. For example, they will continually breach livestock and game fences in the same spot. This results in cattle herds intermingling and high-value game species escaping, leading to serious management problems and large financial losses.

This results in cattle herds intermingling and high-value game species escaping, leading to serious management problems and large financial losses.

Livestock producers farming adjacent to the Etosha National Park have in recent decades occasionally had to deal with elephants on their land, but during the past 15 to 20 years, the problem has increased to such an extent that drastic management solutions are now called for.

State control of elephants, along with licensed hunting, have kept numbers down in the past. Apart from anthrax, elephants do not have any natural enemies. Anthrax is a serious, infectious disease that occurs naturally in soil and affect domestic, as well as wild, animals around the world. In Namibia, the disease has, to all intents and purposes, been eradicated in commercial farming areas, which has exacerbated the unchecked increase in elephant numbers.

Anthrax is a serious, infectious disease that occurs naturally in soil and affect domestic, as well as wild, animals around the world. In Namibia, the disease has, to all intents and purposes, been eradicated in commercial farming areas, which has exacerbated the unchecked increase in elephant numbers.

Competition for resources

Elephant numbers have increased markedly in the northern communal areas over time. The state’s decision to no longer supply water to communal farmers has increased competition between them and the elephants. Communal farms are now forced to pump water for their own livestock, and given the scarcity of natural resources, animals have migrated east to commercial farming areas.

The problem is exacerbated by the ever-increasing land area being allocated to communal farming in Namibia.

The Namibian Ministry of the Environment and Tourism (MET), as well as a number of non-governmental organisations (NGOs), are currently conducting research into the matter. However, it seems as if the research is focusing on monitoring the problem rather than managing it.

The Namibian Livestock Producers’ Organisation (LPO) has in the past investigated various methods of keeping the elephants at bay such as the use of chillies and chilli powder.

In the early 2000s, research by Rowan Martin, an independent wildlife consultant from Zimbabwe, revealed dire overpopulation in the northeastern part of the country, which resulted in ‘unhappy’ elephants. Consequently,

LPO donated four GPS neck collars to track elephant movement, which is a valuable early warning system. Unfortunately, there are still untagged herds in the area that cannot be monitored.

The Namibian government regards elephants as a national asset and, as such, the species is protected. The relevant state departments should therefore take responsibility for the problems we are facing and manage the situation accordingly.

The fact that hunting has been limited to culling elephants that have officially been declared problem animals adds considerably to the rapid population growth.

Virtually no permits are issued for trophy hunting anymore. Meat from the few animals hunted is donated to local communities and part of the income derived from elephant hunting is channelled to the Game Products Trust Fund, among others.

The government does not reimburse communal farmers for damage caused by elephants, which further compromises the already low profit margins of livestock production in Namibia.

Emotional attachment

Organised agriculture engages with government on an ongoing basis with regard to the ‘elephant problem’. However, LPO believes the international community’s emotional attachment to elephants and the outcry that could be elicited by any plan to manage the animals is the primary consideration when approaching the issue.

It is a fact, however, that elephants are not endangered in Southern Africa. The habitat destruction caused by the overpopulation of elephants is a serious problem that is not taken into consideration by some of the parties involved.

It is, however, difficult to determine the full extent of the problem in terms of cattle escaping through damaged fences, or the loss of income when potential trophy game animals are lost in the same way. Financial losses such as the destruction of windmills and submersible pumps have amounted to millions of rands over the past 15 years.

The sad part is that because of poor control and management, and the huge extent of the problem, authorities will be forced to cull entire herds, as was done in the 1970s and 1980s.

Funds need to be made available to move Namibian elephants to other parts of Africa to prevent further habitat destruction as a result of gross overpopulation.

For more information, email Piet Gouws at [email protected], or phone the Namibian Agricultural Union on +00264 1237838.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.