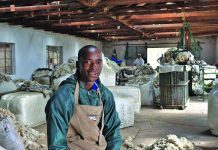

Photo: Lloyd Phillips

Excited about KwaZulu-Natal’s first indigenous goat sale, communal goat farmer, Msawenkosi Thusi, took 35 goats to the temporary sales yard at Msinga and registered as a seller.

As secretary of the Msinga Livestock Farmers’ Association, Msawenkosi decided to lead by example and encourage fellow goat owners on the Mabaso communal land to sell their surplus animals as a form of income generation in this area of high unemployment and poverty.

READ: Lessons from a communal wool farmer

The sale, arranged and facilitated by the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform, the KZN Department of Agriculture and Environmental Affairs and auctioneering company, AAM Livestock Agents and Auctioneers, was a resounding success.

READ: Communal farming under threat

“Many communal goat and livestock farmers keep their animals as a symbol of wealth. They do not realise the economic value of their animals and cannot understand that surplus animals can be sold and the core herd retained, which means that they have livestock and income. Unplanned growth in herds and flocks, with occasional sales or slaughtering, creates overgrazing problems and keeps people poor,” Msawenkosi explains.

In the mid-1990s when asked to quantify the value of his animals Msawenkosi realised that stock had actual economic value as well as material value.

Moment of insight

Msawenkosi has lived most of his life in Msinga in the Tugela Ferry area and also followed the Zulu tradition of holding onto animals and slaughtering only for a traditional ceremony. The turning point for him came in 1996 when five of his cattle went missing.

“I reported my loss to the Tugela Ferry police,” he recalls. “When they asked me about the financial value of the animals, I was confused. After some thought I realised that the lost cattle and my other livestock were worth many thousands of rand. I realised that I could make money if I bred animals and sold the surplus.”

In 1996, Msawenkosi owned Nguni cattle and indigenous goats, both renowned for hardiness and beautiful hide colours and patterns. Later he started breeding sheep to supply lamb to Msinga’s butcheries.

To increase his cattle and goat numbers, he began to buy breeding stock from fellow Msinga stockmen. Limited finance dictated that he could only buy a few cows or ewes at a time.

He selected animals with meatier traits because he intended to start marketing his surplus to community members for slaughter in traditional ceremonies.

Grazing shortages

“I used my own Nguni bulls on my cows and sold surplus animals to community members. But I quickly found that the biggest challenge was to find enough grazing for my growing herd, especially in winter. As Msinga has a harsh dry climate, I decided to keep 20 Ngunis for breeding.”

Until recently, he sold between five and six Ngunis a year. In the early years he got about

R1 600 for an animal but more recently his Nguni heifers sold for R4 000 to R5 000 each at an auction.

Struggling to find grazing land to lease, Msawenkosi had to sell all his cattle last year. He treats this as a temporary setback and looks forward to re-establishing a cattle herd in the Msinga area. His focus now is on breeding and selling indigenous goats.

Diversifying

In 2009, he established a small Dorper and Dorper x Nguni sheep flock and is slowly building this flock to meet local butcheries’ demand for lamb.

He has 34 sheep in his flock but is aiming for 80. Indigenous goats thrive in this arid area. They have been selected over centuries to survive on whatever grazing or browsing was at hand and have high tolerance to pests and diseases. Their main disadvantage is that they have less meat.

To counter this, while striving not to undermine the indigenous goats’ resistance and adaptability, Msawenkosi crosses many of his goats with the hardy, but meatier, Boer goat. He has between 130 and 140 goats, 50% of them pure indigenous goats and the other 50% crossed with Boer goats.

“Goats have always been popular for slaughter during traditional ceremonies,” he explains. “Colour is important to buyers. The favourite colours are white and grey, then brown or red. Spotted goats are not a problem but black goats are unpopular because they are believed to bring bad luck. The red and white Boer goat genetics help reduce black in my herd.”

Msawenkosi is not concerned by a goat’s colour. While other sellers may charge a premium for more popular colours, he pegs his price to the size and sex of the goat.

Difficulties in breeding

One of the problems communal goat farmers face is lack of mating selection. Because animals range freely in large mixed flocks, with no separation, good ewes from one owner’s flock can be covered by poor quality rams from another flock.

Msawenkosi says hiring a full-time herder is not cost-effective so he has to rely on his rams to chase off inferior ‘wannabe suitors’, a method not guaranteed of success.

“I aim to run one ram with every 25 ewes,” says Msawenkosi. “At the moment I only have one ram because one died and a third went missing – presumably stolen.

READ: Top Merino genetics for Eastern Cape communal farmers

“I buy replacement rams from Sandile Ndlela who also breeds indigenous goats x Boer Goats. To avoid inbreeding I replace rams every two years.”

Year-round, Msawenkosi produces between 40 and 50 kids. They are sold to local community members.

Market access

He currently produces between 40 and 50 goat kids annually. A set breeding season is impractical under communal farming conditions. Ewes are mated as they cycle and kids are born throughout the year.

The number of goats Msawenkosi sells in a year depends on available grazing and the cash he has for feed, lick, medication and dip. Currently, his goat flock is at its upper limit for available grazing and the space limitation of his homestead.

For some years, his primary market for indigenous x Boer goats has been his local community. But more recently he has noticed a demand developing among commercial farmers for attractively coloured and patterned indigenous goats.

These farmers breed the goats and sell their hides to tanneries. This market is now more accessible to Msawenkosi since he has been able to sell animals at the indigenous goat sale. Many of the buyers were commercial farmers.

Government’s plan to build a permanent livestock sale yard at Msinga means that regular auctions will be held there in future.

“The prices I got at the auction, from R850 to R1 250 per goat, were very pleasing. If I sell similar goats in the community I usually get lower prices.”

Msawenkosi feels that other communal goat and livestock farmers should see the financial value in their animals and derive an income for them.

“I want to encourage unemployed people in rural areas to do what I do. They often complain that they have no work and no money, but they own cattle, goats, sheep and chickens. They must understand that they don’t have to sell all their animals, but should breed them properly and sell the surplus on a continuous basis.

“The first goat auction in Msinga has opened the eyes of many livestock owners here. The ones who watched but didn’t sell could see what sellers made. Since the auction, many people have called me to ask when the next auction will be. I’ve heard that the next goat auction here will be on 14 November.

“I really love farming with goats, sheep and cattle. It’s in my blood. And it means I can make money to support my family,” Msawenkosi concludes.

Phone Msawenkosi Thusi on 072 184 3121.

This article was originally published in the 03 May 2013 issue of Farmers Weekly.