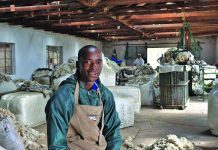

Photo: Susan Marais

Long gone are the days when sheep were produced on sleepy farms where the animals were simply left on the veld for days without having any contact with the farmer. These days, farmers have to manage their flocks with far greater care due to the risks posed by stock theft and predation.

Gareth Angus runs Merino sheep, cattle (Simmentaler and Simbra) and game with his father on Wisp-Will Farm near Arlington in the eastern Free State. He is in charge of the sheep component.

Spring and Autumn lambing

“We divide the sheep into two flocks: a spring- and an autumn-lambing flock,” Angus says.

The spring group lambs from the beginning of September until mid-October, while the autumn group lambs from mid-May until the end of June. Both do so in staggered subgroups.

“Each group of ewes lambs once a year. As a result, we have two lambing seasons per annum.”

All maiden ewes (two-tooth) are put to the ram at 18 months old. Teaser rams are used initially for 11 days at three or four rams per 100 ewes, followed by breeding rams for 34 days at the same ratio.

“I believe young ewes should first be opened naturally before receiving sponges or [controlled internal drug release], which releases progesterone to suppress ewes’ heat or oestrus, as their vaginal canal is still narrow at 18 months and the device used to administer a sponge for synchronisation sometimes hurts them,” says Angus.

After the ewes have lambed for the first time, they are synchronised.

“Every season, I synchronise two to three groups of ewes of about 240 to 260 ewes per group about 10 days apart, after which natural mating takes place.” Each ram covers between four and six ewes.

Angus has ingeniously converted an old bale shed, built years ago by his grandfather, Willy, into a lambing shed.

It houses 150 lambing pens of 2,5m2 each.

“This is a good-sized [pen] for Merino ewes,” he says. “Meat breeds need a larger pen.”

The shed is the ideal facility for the lambing pens, as the animals are sheltered from the elements by the roof and the dirt floor remains dry.

“I only let ewes carrying multiples lamb in these pens. Usually, between 45% and 60% of my ewes carry multiples. All the pens are therefore filled every 14 days.”

Each group of multiple-carrying ewes is put in the lambing pens as soon as the first ewe has lambed.

“The ewes and their lambs are let out of the pens when the lambs reach the right size and vigour. They aren’t let out on a certain date,” says Angus, adding that it usually takes between a week and 10 days before all the animals in a group are let out.

Once all the animals have left the pens, the entire shed is disinfected and thoroughly cleaned before the next group is housed.

After being moved out of the lambing pens, the ewes and their lambs are placed in 5m x 10m camps for three days. Each camp holds 10 ewes and their lambs.

“It’s easier for a ewe to learn to identify her lambs in smaller camps,” Angus explains.

“After three days, the ewes and lambs are transferred to larger camps.”

The spring group grazes mainly on planted pasture, which is a mixture of Smuts finger grass (Digitaria eriantha), lucerne (Medicago sativa) and poor man’s lucerne (Sericea lespedeza).

The autumn group grazes on harvested maize and sunflower lands, or radishes and oats that have been planted specifically for the ewes and lambs. The group continually grows in number, and about two weeks after the last multiple-carrying ewe group has lambed, the three multiple-carrying ewe groups are combined into one flock.

Ewes that give birth to singletons give birth outside in lambing camps between trees. These are between 0,5ha and 1ha in size.

Ewes that lamb naturally (unsynchronised) do so in 100m x 50m jackal-fenced camps. The sheep remain here for at least two weeks before being moved to larger camps or fields.

Own pellet machine

Another way in which Angus has improved the efficiency of his intensive operation is by procuring a Jones pellet- manufacturing machine.

“We manufacture three types of pellets,” he says. “Ewe pellets are given three weeks before lambing and up to a month after lambing. One month post-lambing up to the weaning of lambs, the ewes receive another pellet. The third type of pellet that we manufacture is lamb creep feed pellets.”

The pellets are all manufactured from the Anguses’ own feed and maize, along with high-protein concentrate (HPC) and molasses that are bought in. Angus bought the machine second-hand for R170 000.

“Previously, we spent between R60 000 and R80 000 per [lambing] season just on the lamb creep pellets at the local co-op,” he says. Because they have two lambing seasons on the farm, this added up to about R140 000 a year.

“Our annual costs, two seasons per annum, with own feed and bought-in HPC and molasses meal for the pellet machine, come to R70 000 per annum. This includes electricity.

“We therefore achieve a saving of R70 000 per annum, or R35 000 per lambing season. Over five lambing seasons, there’ll be a saving of up to R175 000 (over 2,5 years) and we’ll break even with the machine’s cost of R170 000.” There is a similar saving on the ewe pellets.

Three weeks prior to lambing, single- and multiple-carrying ewes are split up, and each group then receives its own pellet ration.

“One thing I’ve learnt is that Cryptosporidium and E. coli are always a danger when it comes to intensive sheep farming,” says Angus.

“It’s therefore very important that the lambing pens dry out between seasons. I also disinfect the pens twice with F10 and Kenocox between seasons and dose the lambs on day one, three and five with Elixir Gold and EM, and inject them with a sulfa drug such as Kyrotrim, Sulfatrim, Ecosulf LA or Maxisulf LA.”

All ewes are also inoculated against E. coli and Salmonella prior to lambing.

“Lambs with symptoms are injected with sulfa or Baytril-type antibiotics. They are also isolated as a group with their dams.”

Technology boosts profits

This year, Angus switched his identification system from ordinary colour tags to a radio frequency identification system (RFID), using the BenguFarm software system with a Tru-Test scale.

“It has simplified herd management and is far more accurate,” he says.

Each ewe receives an RFID tag that is scanned by the computer in the crush. “Each lamb also receives a tag, which is linked to the mother. All the information available on a ewe immediately comes up when the tag is scanned.”

The RFID system also makes it easier to manage fertility. A veterinarian scans all the ewes to determine if they are open, or if they are in lamb with singles or multiples.

“Open ewes don’t get a second chance to conceive; they are culled,” says Angus.

To ensure he tracks his herd as closely as possible, he has also written his own Excel program to record all information pertaining to pregnancies.

“We also have a hamel farming operation where some of our ram lambs are castrated and kept after weaning, and sheared every eight months. The hamels are placed in camps with poorer grazing and where it’s more difficult to manage lambs due to predators.”

These camps are generally also more secluded.

The hamels are kept until they are at the six-tooth (B-grade) or eight-tooth (young C-grade) stage. At this point, they are sheared again and sold at livestock auctions. The shearing seasons are in April, August and December, which fits in neatly with the lambing seasons.

“This ensures that we never have ewes that lamb during the shearing season.”

The shearing operation, he adds, can put undue stress on an in-lamb ewe, causing her to abort.

Email Gareth Angus at [email protected]