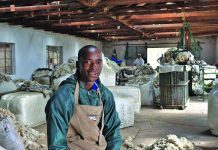

Photo: Eddie Steenkamp

Eddie Steenkamp raises White Dorper sheep on two farms in the Western Cape, Doornboomsfontein near Beaufort West and Karbonaatjieskraal near Hopefield.

Faced with ongoing predation by jackal and caracal, he has spent years designing and perfecting protective collars for his animals.

“I began in 1994 by fitting strips of used inner tube around the lambs’ necks, and later progressed to a ‘bell’ made out of a small steel tin,” he recalls.

Today, he uses two separate devices in tandem, and these, along with a management plan, have dramatically reduced predation by caracal and jackal.

Steenkamp stresses that a predation strategy must be alternated frequently to outwit predators.

“My system is based on the suspicious nature of predators, as well as their ability to learn new behavioural patterns very quickly through experience and observation. They have superbly developed senses of sight, smell and hearing,” he says.

The collar system

Steenkamp’s primary device is a protective and deterrent ‘nail collar’ comprising an adjustable webbing strap fitted with a lightweight tin containing a ball, which functions as a bell. The strap is also equipped with scent blocks, a plastic collar band that contains two yellow reflectors, and eight sharp nails.

According to Steenkamp, this collar should be applied to a lamb within the first three weeks after birth.

“The sound, smell and reflectors deter prospective predators from attacking the lambs, as the predator’s senses (hearing, smell and sight) get the message that these lambs are not normal prey,” he explains.

After prolonged use, however, a predator becomes accustomed to the ‘altered’ prey and does not perceive it as suspicious or threatening anymore.

“Sensing that the strange alterations can do no harm, it then makes an effort to bite the lambs fitted with the collars,” explains Steenkamp.

This is where the nails have proved to be highly effective. The predator goes in for the kill with great force, especially on a lamb Managementfitted with protective material, and the nails pierce its open jaws.

According to Steenkamp, a predator avoids risking injury to its jaws and limbs as these are essential to its survival.

“Unfortunately, some will persevere in their attempts to bite lambs, despite suffering injuries,” he says.

If this happens and predation has occurred, he replaces between 20% and 30% of the nail collars on his flock with poison collars consisting of pouches containing sodium monofluoroacetate (1080).

“The poison collar has no bell, scent block, reflective dots or nails, and is positioned on the throat area of the lamb, which is normally targeted by predators during a kill,” explains Steenkamp.

The hungry predator will target the animals wearing poison collars precisely because they do not appear to be different. Its bite penetrates the pouch, releasing a lethal dose of poison into its mouth.

“Unfortunately, the farmer will lose a lamb, but at the same time the predator removes itself in the process.”

Steenkamp adds that the poison used is biodegradable and does not pose a risk of secondary poisoning. After the predator population has been brought under control, the remaining poison collars are again replaced with the nail collars.

This method enables him to limit and resolve the predation on his farm without having to rely on the collaboration of neighbouring farmers or alternative efforts of any kind.

Results show success

From 1996 to 2012, Steenkamp, using poison collars, managed to eliminate many of the predators killing his livestock, but he still lost about 20 lambs a year from a flock of 1 200 ewes.

Since the introduction of the nail collars in 2013, he has been even more successful at eliminating or permanently deterring problem predators, and the number of lambs killed has decreased.

“From 2013 to 2018, I lost an average of only 13 lambs a year. In cases where a predator actually managed to kill a lamb wearing the nail collar, it hurt itself so badly that it avoided the collars with the reflectors, and the predation did not continue.”

Advice to farmers

According to Steenkamp, predator figures in South Africa are increasing.

For the past 50 years, we’ve learned that if predators are constantly exposed to a control measure, such as wires, traps and collars, they adjust their behaviour so that these controls later have little or no success in controlling them.”

He adds that from 24 years of data gathered during efforts to limit predation, he noticed that stock losses occur largely from May to September.

“This is when the predators’ natural prey availability is at its lowest. The other great lesson I learned over the years is that these animals are territorial where they are allowed to be. This promotes the establishment of areas occupied by certain predators, which limits the presence of other predators.”

Steenkamp recommends that the approach of continually hunting predators should be replaced by efforts to remove only damage-causing predators.

It is also important that farmers manage their lambing seasons to avoid the dangerous May to September period, or keep their flocks in areas where the predation problem is not as severe.

Email Eddie Steenkamp at [email protected].