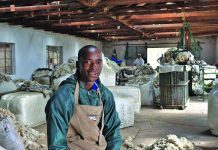

Photo: Glenneis Kriel

Elnora Crous, who farms with her father, Dawie, on Jongensklip near Caledon, uses laparoscopic insemination rather than artificial insemination on their Dohne Merino stud ewes. The goal is to produce top quality rams for their commercial flock.

Laparoscopic insemination is a procedure in which semen is injected into the lumen of the ewe’s uterine horn, enabling a farmer to use top ram genetics in more ewes over a shorter period than is possible with natural breeding.

The procedure in effect helps to accelerate genetic progress, says Elnora.

“For a laparoscopy, you can collect enough semen from one ram in about three sittings, to inseminate up to 200 ewes in one day,” she explains.

In comparison, when natural breeding techniques are used, a single ram is used on about 30 ewes for 30 to 34 days, depending on veld conditions. There is also a greater risk that a ram may injure or overexert itself.

Elnora prefers making use of laparoscopic insemination over artificial insemination, where the semen is inserted into the vagina of the ewe, as it requires the use of smaller volumes of semen per insemination.

“The number of times semen from one collection can be used depends on its quality. I would, however, think you can perform five times more inseminations from one collection of semen with laparoscopies than with artificial insemination,” says Elnora.

Elnora Crous has been farming with her father Dawie for the past six years on their farm, Jongensklip, near Caledon.

Laparoscopic insemination is expensive, and costs about R62/ ewe when semen from one of the farm’s own rams is used.

Recipe for success

Elnora stresses that when it comes to laparoscopy, she is still a ‘rookie’. She has, however, used the procedure for three years and has identified four major factors that contribute to its success.

Firstly, it should be performed by a vet, as it is a highly specialised procedure requiring extreme precision. Secondly, fresh semen should preferably be used.

“You can use frozen semen, but the ‘take’ percentage will be significantly lower than with fresh semen,” she says.

Semen is collected from the farm’s own stud rams or a ram brought in for this purpose and used for insemination on the same day.

Thirdly, the procedure should be as stress-free as possible.

“To reduce stress, we stop giving vaccinations and mineral and vitamin supplements about a month before the ewes are inseminated. You don’t want to meddle too much with the ewes during that month,” she says.

The fourth and most important factor, according to Elnora, is that ewes need to be in good body condition, but not overweight, when the laparoscopy is performed. Ewes undergoing a laparoscopic procedure should have a body condition of 3,5 to four (on a scale of one to five).

Flushing or supplementing ewes just prior to, and during the breeding season, can improve their ovulation rate, and Elnora flushes the ewes with lupins (300g/ ewe/ day) about four weeks before and two to three weeks after the laparoscopy.

Grazing is augmented with an energy feed, such as maize, only if veld conditions are poor.

Ewes receive a commercial bypass protein from three weeks before lambing until lambs are weaned. This ensures that ewes produce enough milk for their lambs and assists them to recover their body condition quicker after lambing.

Lambs receive creep fodder from two weeks of age and are weaned 80 to 90 days after lambing, depending on the condition of the veld. However, weaning should take place sooner during a dry year when feed is scarce in order to reduce stress on the ewes, according to Elnora.

The farm has two mating seasons: April and September. As the April season is the more ‘natural’ season, a higher conception rate is achieved then. The stud is divided into two groups and 100 ewes are inseminated during each of these seasons.

Controlled internal drug-release (CIDR) devices are used to synchronise the oestrus cycles of the stud ewes two weeks before insemination. Two days before insemination, the CIDRs are removed and the ewes receive pregnant mare serum (PMR) to induce superovulation. The dosage of PMR given depends on the size of the ewe.

“While you want the ewes to produce twins, you don’t want to overdo it and run into a situation where they produce quadruplets and are unable to look after the lambs,” Elnora says.

Ten days after the procedure, ewes are placed with a ram in case the laparoscopy was unsuccessful. They are scanned for pregnancy 40 days after the laparoscopy and to determine which ewes are carrying multiple foetuses. The farm currently boasts a 72% take level for the stud.

However, going to all this trouble means nothing if something goes wrong during lambing. One of the significant changes Elnora made after joining the farming operation was to introduce lambing pens or cubicles.

“Having ewes lamb in a defined space helps to ease management and gives you more control over what’s happening. Your lambing percentage is in effect also higher. We have a lambing percentage of about 155% for the stud ewes,” she says.

Elnora prefers larger-than-average cubicules. Those inside the shed are only slightly bigger than normal – 2m x 1m –

because she had to work within the constraints of the existing infrastructure. The cubicles outside measure 2m x 1,5m. All stud ewes lamb in the lambing pens.

Commercial ewes lamb on the veld and are divided into groups according to whether or not they are carrying multiple lambs.

Selection criteria

Elnora selects rams and ewes with sound body conformation and good reproduction values to incorporate into the flock or stud.

At the moment, one of the main breeding goals is to increase the length of wool produced on the farm.

“We calculated that producing longer wool would result in a bigger financial return than trying to go for finer wool. Our wool is relatively fine at an average of 19,3 microns,” she says.

This year, Elnora has changed the shearing regime from every eight months to every six months. “The benefit of shearing twice a year is that it gives you set dates. Previously shearing sometimes had to be undertaken at inopportune times, for example, just before lambing.”

Full support of everyone on the farm

Asked what it is like being a female farmer, Elnora is all smiles. Dawie gives her free reign to do what she thinks best on the farm, unlike many fathers whose sons farm with them.

“I guess it is because my dad and I are very much alike, so there isn’t really any conflict. My dad is also open to new ideas,” she says.

Getting the support of workers and the community was also not difficult, as Elnora grew up on the farm and went to school with some of the employees who work with her today.

As a result, there is mutual understanding and friendship between Elnora and her staff on the farm.

Email Elnora Crous at [email protected].