“My father had SA Mutton Merino sheep and so did my grandfather, so it was inevitable that I would farm them,” says Piketberg farmer Hannes Eksteen. “But European sheep breeds don’t adapt well to the African climate or the diseases we have here. On trips to buy Nguni cattle in Limpopo, I noticed the indigenous Pedi sheep and wanted to find out more about them.”

Then, in 2007, Hannes’s son Lochner – nine years old at the time – asked for some sheep to farm “that didn’t look like the others”. Hannes bought him 15 Pedi sheep, and impressed with what he saw, soon bought some more. “Two years later, after one particularly cold winter storm I lost 22 Letelle lambs in one night, but not a single Pedi lamb died,” he recalls.

“That was the decider for me. At the end of that season I’d sold all my Letelle sheep and switched to Pedi.” Hannes emphasises that his flock of 370 Pedi sheep is easy to manage. Every afternoon at sunset, the flock gathers at the kraal gate waiting to come in.

Pedi pros

“The Pedi has adapted well to our climate and is very resilient, with virtually no disease problems,” Hannes explains. “Ewes are excellent mothers. We don’t assist at lambing and have no lambing problems. The sheep have a strong flocking instinct, domesticate well and are light on veld and water. We get an income from meat, fat and skins and from the sale of live animals.

“I like working with them because the breed has a good temperament, is easy to work with and intelligent. They’ll learn a routine quickly. If I take them to a fresh grazing camp they’ll be waiting at the right kraal gate the next morning to go back in.”

He chuckles. “I can’t help liking them. But with intelligence comes mischief. We cull fence crawlers. Intelligence has disadvantages for a sheep too!”

Climatic considerations

The breed originates from the Venda region in the north of the country and are adapted to hot, tropical conditions. They are not affected by the high summer temperatures of the Piketberg, which can rise to 45°C. Hannes and Lochner prefer the ewes not to lamb in summer. “When it’s so hot, the lambs eat less, the nutritional value of the veld is low and the lambs don’t grow out as quickly,” says Hannes. “But if they do lamb in summer, they can tolerate the heat and the ewes don’t abort.

“In its area of origin, the Pedi lambs in September and October because summers are green. We changed to a March/April lambing season because it suits our climate and environment. Lambs have more time to grow before the summer heat sets in.”

Dietary regime

Last year, Hannes experimented with 350 ewes on 8ha of dryland oats and barley grazing for half a day every day for four months. Doing this helped him to monitor their nutritional needs. “They also drink very little,” he says. “Just in the morning and evening, even in summer.” Hannes has found the breed economical to farm as they are efficient roughage converters. “We give them baled hay and straw and don’t need to mix it with molasses,” he explains. The Letelle sheep needed their hay chopped but the Pedi are not fussy eaters.

“During the lambing season, the ewes, kraaled at night, are fed oats mixed with molasses and feed lime. The molasses helps to bind the lime to the oats, and the lime prevents acidosis. Calcium deficiency is a common cause of lambing problems. The secret to successful supplementation in the diet of lambing ewes is the correct ratio of protein, energy and calcium. Outside the lambing season, ewes are given medics straw when they’re kraaled at night.”

In winter, ewes and lambs graze on oats pasture. In summer, all the sheep graze on veld or wheat stubble in the morning until 10am, then rest to conserve energy. They graze again from about 3pm to 5pm, when they are kraaled in the evening. According to Hannes, they drink mostly water in the kraal, and very few drink during the heat of the day.

The tail tale

The Pedi’s distinctive fat tail is an important adaptive advantage. Fat reserves stored in the tail can be used when they are needed, especially at lambing. The fat reserve in the tail often disappears at this time. “Modern European breeds don’t store fat and depend entirely on daily nutrition but a Pedi can fall back on its fat reserves if immediate nutrition is insufficient,” says Hannes. “It builds up reserves in good times for lean times. “Rams are easy to keep and don’t need much feed. I run them separately from the rest of the flock but put them in with the ewes for six weeks a year.”

Disease resistance

Pedis are naturally resistant to redwater and heartwater, but these diseases are rare in the Western Cape anyway. According to Hannes, the breed is also resistant to blue tongue, foot rot and many other diseases. “We had foot rot problems during the wet season with the Letelle but even with kraaling, it’s not a problem with Pedi,” he explains. “We only inoculate against Chlamydia because it causes enzootic abortion in ewes, and treat for internal parasites and nasal worm.”

Two years ago, Hannes and Lochner started precautionary inoculation of ewes two months before they put the rams in.

“We’ve had no stillbirths from inoculated ewes this year, and only two from bought-in pregnant ewes,” says Hannes. “Six weeks before lambing we start treating for internal parasites and nasal worm, which is the norm for all sheep.”

Kraaling

The Pedis are kraaled every night. “There are leopard and caracal in the mountains and we must also protect ourselves from stock theft. So bringing them in at night makes it easier to monitor lambing ewes,” Hannes explains. “We also keep ewes with new lambs back for two days in a camp near the house so that the lambs can gather strength to keep up with the flock. Every evening the flock returns to the kraal and waits at the gate.”

Historically, the Pedi is a breed that has been kraaled, as it originated in areas with predators. “Kraaling improves control over the animals because we can see all the sheep daily and easily spot sick individuals. The disadvantage is we’re restricted by how many animals we can keep in one kraal. Overpopulation in a kraal increases the risk of disease and makes for more difficult management. Enlarging the kraal isn’t a solution. The only answer is to provide a second kraal.”

Breeding cycle

Hannes has only one lamb crop a year and between 20% and 30% of lambings produce twins. He admits that the Pedi has not been specifically selected for twinning and could be seen to be less productive than European breeds of sheep with their higher rate of twinning.“We put the rams in with the ewes from mid-October to the end of November,” he says. “Lambing is from mid-March to the end of April and we wean in September.”

Weaned ewe lambs go to the rams in October, to lamb with the older ewes the following season. Young ewes do not skip a year before they lamb. “Ewes suffer no lambing problems and have no uterine prolapses,” explains Hannes. “The secret is in the tail. As the sheep continually wags it, the muscles around the tail are kept strong, which prevents uterus prolapse. Letelles have their tails docked and they have problems during the lambing season with uterus prolapse, orphans and blow-fly strike.”

Some of the ewes are now 10 years old, and Hannes maintains that a good Pedi ewe will produce at least one lamb a year from the first year until she is eight or even 10 years old.

Limited farm Capacity

“The farm is large enough for 400 ewes and we’ll probably reach that number soon,” says Hannes. “For 400 ewes we only need 12 rams. “I can think of only one reason for more people not farming Pedi sheep in the Swartland: they haven’t yet thought of it and continue to farm with what they know.” Hannes has found the Pedi to be highly profitable. It also suits his farming style as he can kraal the sheep near the house at night.

“The bigger the flock, the higher the profit, as overheads and labour costs are roughly the same,” he explians. “The Pedi isn’t labour-intensive. Lochner runs the flock mostly by himself, and really only needs a helper when dosing or sorting sheep.”

Marketing pedi meat

Hannes believes that Pedi meat tastes better than that of other breeds. “There’s a substantial market from butchers in the Western Cape for wethers, especially in winter,” he says. “The fat reserve that accumulates in the tail of these sheep can easily be removed and used for other purposes. The fat has a speciality market as hunters are keen on the tail fat to make droë wors.

“There’s an excellent market for live Pedi sheep and I sell rams and ewes to farmers who want to establish their own flocks. Time will tell if the Pedi sheep becomes more popular in this area but I wouldn’t choose to farm any other breed of sheep now that I’ve seen how easy it is to work with Pedis and have experienced their productivity and resistance to disease.”

Planning for the future

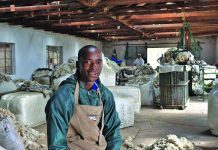

Lochner is already fully involved in the enterprise. While Hannes owns the sheep and is the decision-maker, Lochner, now 15, is the flock manager and does 90% of the daily chores before and after school. He checks the sheep twice a day, and does the sorting and dosing. He also knows every animal’s lineage. It’s a system that seems to be working efficiently and helping to increase the size of the largest Pedi sheep operation in the Piketberg.