Photo: Lloyd Phillips

Stored fodder is essential winter nutrition for the BG Miles Partnership stud and commercial beef and sheep farming operation in the Eastern Cape’s Cedarville area.

The family business, run by Deal Miles, his father, Benny, and sister, Rown, includes about 2 200 Dohne Merino mutton and wool breeding ewes, and approximately 350 Bonsmara beef breeding cows and their followers.

The farm lies in an area that receives an average annual rainfall of only 650mm to 680mm, mainly in spring and summer. Winters are usually frosty, with the minimum daily temperature dropping to below freezing.

According to Miles, these tough winter conditions quickly and substantially reduce the palatability, quality and quantity of the farm’s’ sourveld natural grazing, making stored fodder a virtual necessity. Without this resource, the number of animals would have to be reduced significantly every year, which would not be feasible either practically or financially.

In addition, producing stored fodder helps keep the animals on as stable a plane of nutrition as possible all year round.

“Yet another reason for producing stored fodder is that female animals simultaneously lactating and nurturing a foetus need especially good-quality supplementary nutrition during late winter and early spring, when natural grazing is at its poorest,” says Miles.

“As soon as a calf or lamb is born, we want it to achieve maximum average daily weight gain via its dam’s milk because this contributes to money in the bank for us when the progeny are weaned and sold.”

Maximum consumption

Miles explains that the increased carrying capacity generated by stored fodder pays for the running costs of the tractors, drivers and implements required to produce the fodder in the first place.

However, to cover these costs properly, a sizeable number of productive animals must use this resource. Because understocking is not financially viable, planning is needed to ensure that all stored fodder is used as efficiently as possible.

Miles adds that growing and harvesting stored fodder maximises utilisation of the yield potential of a particular land.

“On our farm, the natural sourveld can produce an average of 2t/ha/year of dry matter for grazing. In contrast, the planted pastures we harvest for stored fodder yield between 5t/ha/year and 7t/ha/year of dry matter. But the sourveld grazing is free, whereas it costs money to grow and make stored fodder. That’s why it must be utilised as efficiently as possible.”

Another advantage of their planted pasture, according to Miles, is that it generally grows and yields better in the family’s medium-potential arable soils than maize planted for silage production would be. Maize usually requires higher-potential soil for optimal yield and return on investment.

He adds that the management and financial risk of growing planted pasture as stored fodder are both less than they would be producing silage maize in their operation.

This calculation, he explains, takes into account the collective cost of soil preparation, harvesting, labour and machinery operation. In his experience, the expense of storing and distributing fodder from planted pastures are also lower than for maize silage and even for stored maize grain.

“A farmer producing and utilising stored fodder must ensure that the resultant increased carrying capacity of the livestock enterprise, and the productivity of the animals eating the stored fodder, always outperform the costs of producing and utilising it. I’ve calculated that to achieve this, the reconception of our mature breeding ewes and cows must be at least 90%, and the conception for our maiden ewes and heifers must be at least 85%.”

The species of dryland planted pasture grown on the farm and stored as fodder are typically poor man’s lucerne (Sericea lespedeza) (110ha); the Kromdraai variety of African lovegrass (Eragrostis curvula) (80ha); and a combination of teff (Eragrostis tef) and pearl millet (Pennisetum glaucum) (33ha). The family also grows 40ha of irrigated cocksfoot (Dactylis glomerata).

Minimum requirements

Miles explains that after years of producing stored fodder for the operation’s livestock, he has developed a fair idea of the minimum requirements needed to make the process cost-effective and efficient. His advice to farmers is to use the following:

- Two tractors in the 55kW to 65kW power range.

- A contra-rotating four-disc mower capable of cutting any density of fodder plant material at any height. Contra-rotating discs are essential to prevent packing of the material during cutting and clearing.

- A tedder for working with thicker-stemmed fodder species, such as pearl millet, sorghum (Sorghum bicolor) or lucerne (Medicago sativa). The tedder is used to fluff up and spread the mown material of these species for enhanced air flow. This promotes faster drying and reduces the risk of spoilage due to rot.

- A simple Acrobat rake. Even better is a more expensive power rake or speed rake as it operates much faster and ensures that the windrows are more even, for quicker, better-quality baling.

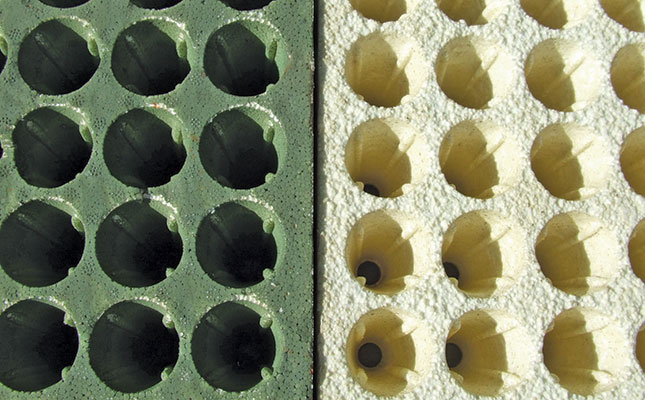

- A round baler. If the baled plant material is to be wrapped in plastic for conversion into silage, the round baler should be fitted with multi-crop cutting attachments to allow for chopping longer plant material into shorter lengths. This promotes fermentation within the wrapped bale. For silage, the round baler should also be capable of packing the plant material densely. This forces air out of the bale, thereby enhancing the anaerobic environment needed for making silage. Correctly ensiled fodder

is more palatable to livestock, and the shorter lengths of plant material are easier for the animals to eat and more digestible. - A bale wrapper, if the farmer wishes to ensile the bales.

Fortunately, explains Miles, a wide range of competitively priced stored fodder-making equipment is available today.

“It’s amazing that even much of the cheaper and simpler equipment is so good at what it’s intended for.”

He cautions, however, that a farmer should ensure that the fodder-making equipment can perform its work effectively and efficiently. Arguably the most important factor in this regard is to maintain the equipment according to the manufacturer’s specifications, both during and out of the fodder-making season.

Properly maintained equipment should be given a careful once-over just before the season commences to make sure it is in perfect working order. A single breakdown can compromise the entire fodder-making process.

“If mown plant material lies on the ground for a long time because an improperly maintained baler has broken down, the plant material will lignify, lose its nutritional value, and become less palatable to the animals,” explains Miles.

“The entire fodder-making process needs constant management to ensure that the quality and quantity of the stored fodder are maximised.”

He adds that well-produced fodder can be stored outdoors for two to three years. The bales should be stored where they are not at risk from fire, and should be made sufficiently dense to protect their contents from becoming soaked by rain.

Fodder baled while wet, or which becomes wet from rain, can become mildewed; this poses a major health threat to livestock due to growth of Clostridium botulinum bacteria, which produce the deadly botulin toxin.

The true value of stored fodder

“I estimate that without our planted pastures and the stored fodder that we make from them every year, we would need to carry about 30% fewer livestock on our property,” says Miles.

“To make matters worse, the weaning weights of our lambs and calves would be lower. Our entire production management would have to change to a summer lambing season, which would come with increased parasite problems and sudden extreme weather changes.

“Both of these [issues] would significantly increase our lamb mortalities.”

Email Deal Miles at [email protected].