The aim of government’s land reform programme was to transfer some 25 million hectares of farmland (30% of the total) to black communities by 2014. It was envisaged that this had to be done in a manner that would promote sustainable development, making use of available resources.

By 31 December 2016, the Commission on Restitution of Land Rights had settled claims on approximately two million hectares of agricultural land:

- 85 523ha in the Eastern Cape;

- 59 516ha in the Free State;

- 9 817ha in Gauteng;

- 217 624ha in KwaZulu-Natal;

- 436 006ha in Mpumalanga;

- 489 646ha in the Northern Cape;

- 282 731ha in North West; and

- 10 705ha in the Western Cape.

How successful has redistribution been?

There were various programmes intended to facilitate redistribution. The Settlement Land Acquisition Grant (SLAG) programme, which ran from 1997 to 1999, enabled individuals and groups to obtain a grant of R15 000 per household to buy land directly from willing sellers.

This failed to provide sustainable solutions, and many of the projects became poverty traps. Each grant was too little to purchase land, so beneficiaries had to pool their resources to buy the land.

The Land Redistribution and Development Programme (LRAD), implemented from 2001, was geared more towards establishing black farmers. Grants between R20 000 and R100 000 were made available, and beneficiaries were also required to make a contribution.

The LRAD made grants available to individuals, which meant that more than one individual per household could qualify. The programme did work in some cases, and many who would otherwise never have acquired land for farming did so successfully.

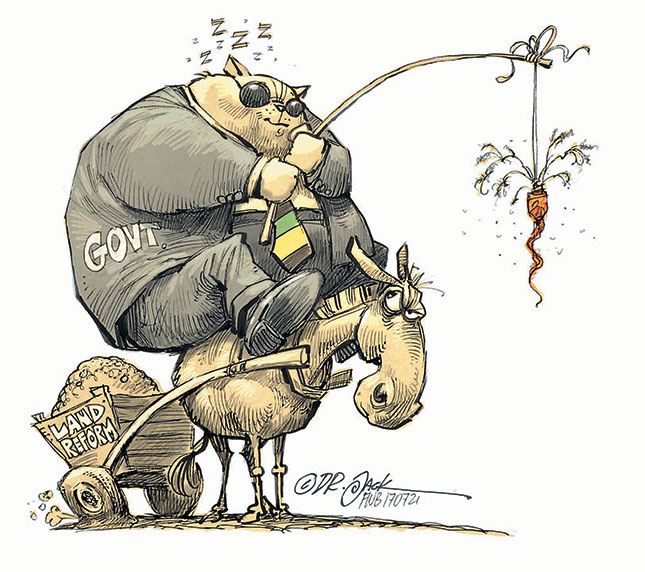

In general, however, these programmes failed because only a small percentage of the national budget was allocated to land reform and supporting land reform beneficiaries.

The Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (DAFF), and the Department of Rural Development and Land Reform (DRDLR), received only 2,5% of the national budget, and consequently, one has to ask if government is serious about land reform.

Success or failure cannot be viewed in isolation, but must be seen in the context of support programmes. The lack of timely and proper support has often caused failures. If we want to succeed with agricultural reform we must realise that post-settlement support costs money.

Two-thirds of funds for reform must go to post-settlement support, with the remainder going to acquisitions.

In 2006, the Pro-Active Land Acquisition Programme (PLAS) was launched to replace LRAD.

The theory was that land would be ‘warehoused’ by government, and beneficiaries could get ownership after a period. In practice, anecdotal evidence seems to be that the state ended up permanently owning the land acquired.

Rather than coming up with a new scheme for redistribution each time, should we not focus on building on the elements of the existing schemes that seem to work, and fix the elements that are not working?

We are making the same mistakes made before 1994, and are again relying on race-

based policies when appointing technical expertise. A developing country such as

South Africa cannot afford to appoint experts who lack expertise, regardless of

race.

In agriculture specifically, black and white must make their voices heard. Let’s

get white farmers to assist black farmers; let’s get black experts to assist whites. The Constitution emphasises a non-racial society, but we are so obsessed with achieving racial demographic representation at all levels of government that we run the risk of diluting expertise.

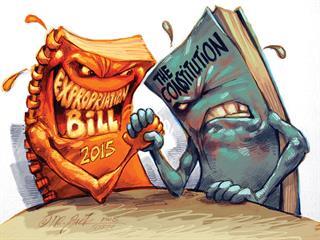

Was ‘willing buyer, willing seller’ the real problem?

The ANC often blames the slow pace of land reform on the so-called ‘willing buyer, willing seller’ approach.

What is the real problem?

Not enough willing sellers?

Landowners demanding excessive prices for land?

Corruption?

Inadequate budgets?

Between 4% and 6% of agricultural land is traded annually, and there are currently around 20 000 farms on the market. There’s no shortage of willing sellers. If only 2% of this land had been bought up annually by the state since 1994, a total of 44% of all agricultural land would have been redistributed by now.

There may well have been incidences of landowners trying to profit from land reform, but there was no obligation on government officials to buy at the inflated prices.

If indeed inflated prices were paid, it must be ascribed either to government officials’ inability to value the land properly or negotiate competently, or to corruption, where government officials wanted a cut of the allocated funds.

International best practice for successful land reform

Asia has had successful reform that has spurred economic success. But Latin America has failed to achieve this same success despite its own attempts at land reform and economic restructuring.

An analysis reveals five major differences between the two regions’ reform models.

Throughout Latin America, land reform was used as a political tool for constituency-building, and incorporated Marxist ideologies.

In contrast, Asian reforms incorporated the landowners they were displacing by involving them in the local land committees that valued and redistributed land.

Asian reforms were implemented on purely economic and shared growth rationales, rather than political constituency-building, even though they succeeded with the latter as well.

The communal ownership and collective production aspects of the Latin American reforms were done away with in the successful Asian models. Instead, Asian reforms focused on individual ownership.

The market-based model of Asian land reforms leads to the third important difference: clear, unhindered title to land was prioritised and occurred far more frequently in Asia than in Latin America.

It must be emphasised that when the focus shifted from huge groups to individuals who had skills and were prepared to, and could, contribute financially, the reform model was successful.

Our appeal to government is to focus on individuals and so ensure black commercial farmers’ sustainability. There are successful black commercial farmers and they must be supported.

An important part of land reform is offering technical agricultural services to beneficiaries after redistribution. Redistribution is not enough in itself, but must be reinforced by technical capacity building.

Latin America’s reforms could not meet beneficiaries’ technical needs.

A consolidated approach

DAFF wants to develop 400 000 small-scale farmers from a budget of R800 million. Divide these figures, and you end up with R900 to R2 000 per farmer. The department says it wants to buy equipment, seed and fertilisers, but you won’t get far with R2 000 per farmer.

We also face a fragmented approach, and have a situation where money is allocated to DRDLR, DAFF and the Department of Trade and Industry. We need to have a consolidated approach.

The best would be to allocate funds to the Land Bank, which would fund black farmers, then task Agriseta with training black farmers, and DAFF with assisting with post-settlement support.

DRDLR must make sure that land is bought and transferred with title deeds to those who want to approach commercial funders.

Finally, organised agriculture plays a huge role and we must start asking questions about why we do not achieve our goals, and why government departments are not being held accountable for not achieving their goals.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

For more information, email Agri SA media liaison, Thea Liebenberg, at [email protected], or call 012 643 3434.