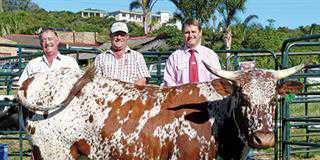

Photo: Mike Burgess

“The Merino is the world champion in wool,’’ says Goodman Ginyigazi (51). “I advise people to go straight for it.’’ In 2004, Goodman farmed a small flock of 60 Dohne Merinos. Now, 12 years later, the former teacher has transformed his flock, and currently farms 261 pure Merinos, including 150 breeding ewes, as well as a small flock of crossbred goats.

Goodman’s dedication to wool production has paid off; he generates over R50 000/ year from his wool clip, and for five consecutive years (2009 to 2013) his flock received the Eastern Cape Department of Rural Development and Agrarian Reform’s (ECDRDAR) award for the best Eastern Cape communal fine wool clip.

Determined to improve production, Goodman has bought Merino flock sires from Merino stud farmers such as Peter Cloete in Dordrecht and Andries Pienaar in Colesberg, since 2006.

“My focus was on wool production and quality,’’ he recalls. “So from the beginning, I bought my own rams.’’ He explains that buying in rams has significantly improved the quality and quantity of wool produced by his flock, which, in 2015, amounted to 6,5 bales averaging 17 to 19 microns.

Goodman Ginyigazi, with a Merino ram, near Lady Frere in the Eastern Cape’s former Transkei.

Nutrition, breeding and health

The majority of Goodman’s flock is run in the mountainous areas near Lady Frere, where the grazing pressure is not as intense as on the populated, lower-lying areas of the region.

Sheep receive a protein lick and/or salt in winter, and no supplementation in summer. Around Goodman’s homestead, roughly 1ha is under irrigation and planted to oats and lucerne. This is used to support livestock when necessary.

Ewes are mated in groups of 30 to four rams in two-week periods, and lambing takes place from September. Mating is managed by relocating breeding flocks to Goodman’s homestead, where a shepherd ensures that no stray communal rams gain access to them.

Because of poor grass availability and the lack of extra feed during winter, a lambing rate of only 70% was achieved in the last breeding season.

Sheep are dipped in a communal plunge dip in May, and then again after shearing in October/November. Goodman works closely with Dr Alan Fisher, state veterinarian at the Queenstown Provincial Veterinary Laboratory, and adheres strictly to the dipping, inoculation and dosing programme Fisher designed for his specific requirements and demands.

“These programmes helped me a lot,’’ he says. “There was a great change in my livestock.’’

Genetic diversification due to several studs

Goodman says that he has attempted to genetically diversify his Merino flock over the past decade, and besides buying in rams, he also buys in, on average, 10 replacement ewes from various Merino stud breeders annually.

“I tried to buy from different people so as to introduce as much genetic variety as possible,’’ he says. “Today, I can see that there’s a great change.’’ Confident in the quality of his sheep, Goodman markets breeding stock at a premium – including 12-month-old rams and ewes sold at R1 200 each – to communal sheep farmers across the former Transkei.

“I’m not a stud breeder, but I try to breed quality sheep,’’ he says. “My sheep are in demand, with people coming from as far as Engcobo.’’ Hamels (castrated rams) and old ewes, as well as breeding stock are marketed at informal markets for slaughter, and generate approximately R70 000/year.

Communal land challenges

Goodman’s greatest challenge are the restrictions of communal land tenure. “It’s not easy at all,’’ he says. “We have a lot of problems concerning communal land.’’

Communal grazing and a lack of fencing is particularly problematic, as Goodman must keep his sheep separated from other livestock to ensure the genetic integrity of his flock and protect his animals from parasites and diseases, such as red lice and sheep scab disease.

Goodman explains that shepherds are thus a critical component in his sheep farming enterprise, as they keep his sheep separated from other livestock by day. However, his sheep and goats have to be kraaled at night, which negatively effects production, and increases the risk of foot rot.

Limited forage resources, a result of excessive grazing pressure, is another challenge. As numerous farmers share the communal land, grass is limited and particularly scarce in winter. Furthermore, cultivating land as an individual is mostly restricted to areas around the homestead, and therefore the significant production of extra feed is largely impossible.

Because of this, Goodman says that he must purchase significant quantities of supplementary feed amounting to about R40 000/ year, including lucerne, from as far away as Cradock.

“It’s a great challenge because the money gained from our sheep we spend on extra feed.” There’s little that they gain for their own betterment, he says.

Land problems, and lack of state support

Goodman says that since 2009, he has unsuccessfully approached the state’s land reform structures in an attempt to source land. “I got nothing,’’ he says. “I went to ask for support, but in vain.’’ He firmly believes that farming on a commercial farm would allow him the independence to produce top quality Merinos for emerging/communal farmers.

“If I can get a farm, I want to show people that here in the Eastern Cape I can produce quality Merino rams and ewes for people,’’ he says. “On communal land, you have restrictions and you can’t just go on.’’

Only the best

While he received two Boer goat rams from the ECDRDAR in 2013, and fencing from the Chris Hani District Municipality in 2014, Goodman has exempted himself from certain state services and offers.

For example, despite the distribution of rams by the National Wool Growers’ Association (NWGA) and ECDRDAR to communal farmers, he prefers to purchase his own rams from stud breeders to ensure control over the acquisition process.

“I decided not to take them [rams from NWGA/ECDRDAR] because I heard and saw from other guys that those rams were not so strong in terms of wool production and mating,’’ he recalls.

Similarly, he says that state-funded inoculation, dipping and dosing programmes are often not as beneficial and cost-effective as the programmes used by commercial and stud farmers, and so he has opted to exclude himself from these programmes. “With research from commercial farmers, I realised I could get onto better programmes for my sheep.’’

Doing it alone

Goodman shears his sheep in the double garage of his home, instead of using communal shearing sheds, to prevent the cross-contamination of wool. As he is yet unable to afford a wool press, Goodman and members from his family compress wool bales using their feet.

All bales, marketed through CMW, are personally transported to auction in Port Elizabeth. While Goodman’s goat flock, which includes 50 breeding ewes, are mainly sold into the informal markets and generate a significant income, Goodman insists that producing good-quality, fine wool is his passion.

“I focus only on sheep farming,’’ he says. “Nothing else.”

Phone Goodman Ginyigazi on 083 781 2872.

This article was originally published in the 08 July 2016 issue of Farmer’s Weekly.