Imagine walking into a piggery in 2030. Hundreds of pigs move calmly around their pens, while overhead cameras track their weight and growth in real time. Thermal sensors pick up subtle changes in skin temperature, flagging early signs of illness.

Automated feeders dispense individually tailored rations, and climate-controlled ventilation systems quietly maintain optimal air quality and temperature. Data analytics predicts growth rates, flags potential issues, and even simulates environmental impacts before they occur, creating a farm that is efficient, humane, and sustainable.

In this high-tech piggery of the future, the role of humans has shifted. Instead of dozens of stockmen checking animals and managing feeding manually, just a handful of skilled operators – and with the arrival of robots, possibly only one – is needed to oversee the entire operation from a central control room.

They monitor dashboards, which can be accessed from anywhere in the world, and fix equipment that these automated systems cannot fix themselves.

Adoption in South Africa

Most of the technologies powering this vision already exist, with many already used in South Africa.

Dr Peter Evans, lead veterinarian of the Red Meat Industry Services Operational Centre, has extensive experience in the pig industry. He told Farmer’s Weekly that South Africa’s commercial pig farmers are among the best in the world, with most large-scale operations already using RFID ear tags for identification, record-keeping, and traceability purposes.

Many are also using automated feeders to improve feeding efficiency and reduce wastage, as well as automated ventilation and climate control systems to create a favourable environment for optimal pig health and growth.

“The average size of piggeries in South Africa has grown substantially over time, as is the case in the EU and US, to gain economies of scale. The average piggery these days can accommodate around 1 500 sows,” he says.

Incorporating technologies into these systems helps reduce the number of labourers required, which in turn improves biosecurity as the chance of someone bringing a disease in from outside, or spreading a disease between houses, is lowered.

South African farmers, nevertheless, have been slower to adopt some of the more advanced monitoring technologies, such as camera-based weight estimation, wearable sensors, thermal imaging, and microphone-based health detection.

“In South Africa, unlike Europe, the US and Australia, we still have access to highly skilled labour, so the cost of replacing labour with machines often does not justify the investment,” Evans explains.

“Farmers here will adopt technologies if they see that the return on investment is worth it, as is evident from the widespread use of RFID tags, automated feeders, and climate control systems.”

This situation is not unique to South Africa. In the article ‘Smart Pig Farms: Integration and Application of Digital Technologies in Pig Production’, published in Agriculture 2025, 15 (9), 937, financial barriers are identified as one of the biggest hurdles to adoption internationally, particularly for small- and medium-sized farms (see doi.org/10.3390/agriculture15090937 for the full article).

Other barriers include fear of technology and resistance to change, data privacy and security concerns, and challenges related to data accessibility, system compatibility and the need for specialised technical knowledge to operate and maintain these systems.

However, as the global demand for pork rises and the pressures to enhance efficiency, sustainability and animal welfare intensifies, the pig farming industry is embracing a wave of innovative technologies.

These advancements aim to revolutionise various aspects of pig production, from reproductive management to health monitoring and environmental control. Here are some of the cutting-edge technologies:

Heat Stress Monitoring

Automated climate control systems are typically programmed to maintain temperature and humidity within an optimal range. Farmers without access to such technology must manually adjust ventilation, heating, or curtains to keep pigs comfortable. This is crucial, as pigs that are feeling too cold or too hot become stressed, which negatively affects their growth and health.

Without automated systems, farmers must monitor both the climatic conditions and the pigs for signs of heat or cold stress. Heat stress can be identified through excessive panting, open-mouth breathing, increased vocalisation, scattered lying behaviour, and a loss of appetite.

In the US, the Department of Agriculture has developed the HotHog smartphone app, which uses localised weather data to alert producers when pigs are at risk of heat stress.

Farmers can then take pre-emptive measures, such as providing extra drinking water, cooling pigs with fans or misters, or limiting transport to early morning hours. According to the department, US pig farmers lose an estimated US$481 million (about R8,3 billion) annually due to heat stress, highlighting just how critical effective monitoring can be.

Optical Identification

While RFID tags have proved a valuable method of identifying pigs, researchers are already pushing for something more advanced: the use of machine learning and image sensors to identify pigs based on facial recognition and other bodily features.

The benefits of facial recognition are clear. It is non-invasive, reduces handling stress, improves traceability, and supports data-driven management. It can also be linked to other digital technologies, providing insights into pigs’ movement and behaviour.

Despite its promise, there is still some way to go before optical identification is widely adopted. The technology is expensive, requires good lighting and camera positioning, and depends on artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms that must be carefully trained for accuracy.

Researchers also found that recognition accuracy dropped from 97% to 69% as the training-test gap increased from zero to 24 days, according to the study ‘Cross temporal scale pig face recognition based on deep learning’, published in the Journal of Agriculture and Food Research, Volume 21, June 2025. The decline in accuracy is attributed to facial changes caused by short-term growth.

The findings suggest a new direction for practical applications of pig face recognition.

Rather than focusing solely on individual classification from static images, neural network architectures should be designed to capture dynamic facial changes over time. Combining such models with metric learning approaches may improve recognition stability and generalisation, making optical identification more viable in real-world pig farming, according to the researchers.

Wearable health monitoring

Wearable sensors can be attached to pigs to monitor vital signs such as heart rate, body temperature, and activity levels in real time, as is already done in the intensive diary production systems in South Africa to detect heat and early signs of illness, lameness or stress before visible symptoms appear.

The alerts generated by the system enable prompt intervention, increasing heat detection accuracy, reducing the spread and cost of managing diseases, and improving overall herd welfare.

Farmers can receive notifications directly on smartphones or tablets, making management more efficient even when staff are not physically present in the pens.

Thermal imaging

Instead of relying on thermometers to measure body temperatures, thermal cameras detect subtle changes in pigs’ body heat, thereby allowing farmers to identify animals that are unwell or in heat without disturbing them.

Thermal imaging is particularly useful for detecting respiratory infections, inflammation, fever, or localised injuries that can otherwise go unnoticed until they start affecting growth or reproduction.

For oestrus detection, subtle changes in skin temperature around the vulva and other regions can indicate that a sow is in heat, enabling timely breeding and improved conception rates.

The technology integrates well with other digital monitoring tools, feeding into farm management software that can log temperature trends, alert farmers in real time, and even help predict outbreaks before they become serious. This continuous, non-invasive monitoring reduces labour demands and stress on the animals, while supporting proactive decision-making.

Body weight

In intensive pig production, monitoring pigs’ body weight is crucial for assessing growth, health, and overall welfare. Traditionally, weights were estimated visually or measured manually using scales, which is time-consuming, labour-intensive, and stressful for the animals.

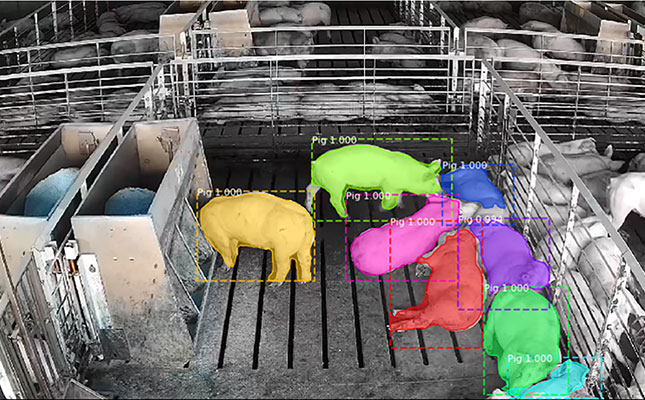

Today, precision livestock farming technologies are changing the game. Cameras and sensors are used to capture high-resolution images of pigs, while machine learning is used to calculate body dimensions from these images, such as length, width, surface area, and volume, to determine weight.

Systems such as Weight-Detect, Pigwei, eYeScan, Growth Sensor, and OptiSCAN are leading examples.

Automated body weight estimation offers multiple benefits. It serves as an early disease detection mechanism, as changes in weight often indicate illness or feed or nutritional problems. It also helps to improve management by allowing farmers to make data-driven decisions for feeding, breeding, and growth optimisation.

Sound-based solutions

Automated sound-based approaches are being explored to analyse pigs’ vocalisations and detect signs of stress, illness, or behavioural changes in real time. However, several challenges are experienced with this solution, according to ‘A review of sound-based pig monitoring for enhance precision production’, published in the Journal of Animal Science and Technology, 31 Mar 2025, 31; 67 (2): 277-301 (see doi.org/10.5187/jast.2024.e113).

Piggeries are inherently noisy environments, with machinery, human activity, and other animals creating interference that makes it difficult to isolate relevant sounds. Pigs also produce a wide range of vocalisations, each of which can indicate different states, from normal behaviour to stress or illness.

Additionally, the installation and maintenance of high-quality acoustic systems can be costly and require technical expertise. Furthermore, a lack of standardised protocols for sound data collection and analysis makes it difficult to compare or integrate data across farms. Data privacy and security are additional considerations, as continuous monitoring could potentially expose sensitive information about farm operations.

Despite these hurdles, the authors argue that the future of sound-based technologies is promising. Advances in AI and machine learning are improving the accuracy and efficiency of sound analysis.

Integration with other precision farming tools, including Internet of Things devices and real-time data analytics platforms, can provide comprehensive monitoring solutions that track health, welfare, and environmental conditions simultaneously.