Photo: FW Archive

The only fundamental difference between intensive broiler production and intensive fish-rearing in terms of livestock production practices, is that the latter takes place in water.

Apart from that, the basic concepts of breeding, rearing, harvesting and marketing are all very similar.

Therefore, because chicken production is considered to be ‘agriculture’, so should aquaculture. However, aquaculture, a relatively new branch of agriculture, especially in South Africa, is regulated to a far greater extent than any other part of the industry.

Despite aquaculture being a potential source of employment, as was an originally stated goal of government’s policy with regard to the sector, the state burdens aquaculture with a vast amount of legislation.

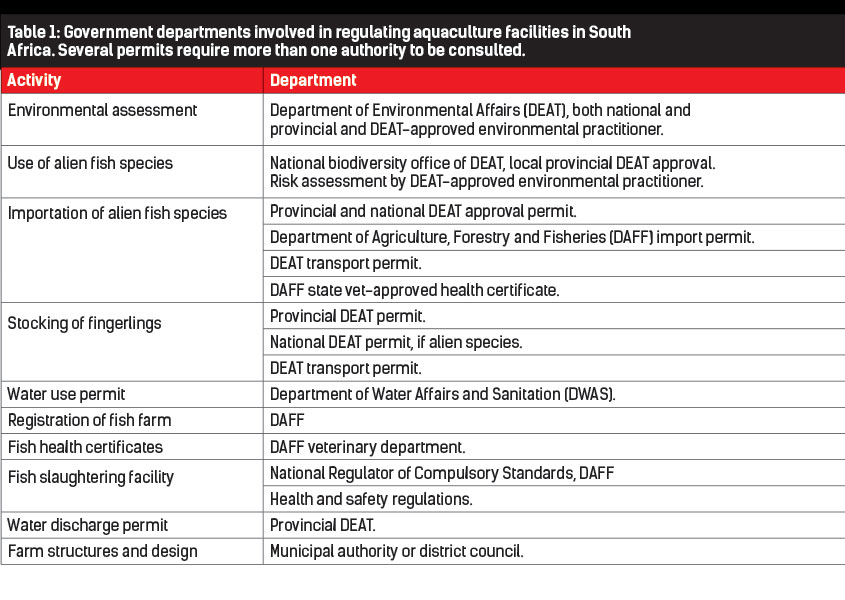

The number of state departments that have to be approached before a serious commercial investor can participate in the sector, is summarised in Table 1.

In most other sectors of the agricultural industry, producer organisations undertake most of the regulation of a particular commodity. This begs the question; why has aquaculture been singled out for such attention?

The current administration’s intention of having all sectors of the economy under state control are well documented. From controlling aquaculture, it is a short step to take control of the entire agricultural sector, including the game farming industry.

The constitutionally enshrined ‘right to farm’ can easily be circumvented through regulations and prohibitions that are out of all proportion to the perceived threats justifying such legislation in the first place.

Well-meaning conservationists

In the aquatic environment, well-meaning but naive ‘conservation scientists’ often support restrictive legislation governing aquaculture development, as it serves their interests and need for funding.

Those involved in the field of invasion biology support steps to restrict the use of commercial alien species, in the belief that it achieves a goal that is erroneously regarded to be morally superior.

According to this belief, all alien species are bad, and if it is indigenous it must, by implication, be preferable.

However, the human factor – people being part of the environment – is ignored.

This philosophy, while credible in protected areas, makes no allowance for the fact that virtually all agriculture, and therefore food production, is based on either alien or genetically improved species. Natural resources should thus be sustainably used for human benefit.

In South Africa, environmental officials effectively set aquaculture policy at provincial level for every existing and new aquaculture project. These policies are then extended to national level.

This approach is justified by echoing conservation organisations and purist scientists’ claim that “the mistakes of the past should not be repeated”. These mistakes are, however, never clearly spelt out.

Stakeholder participation by members of the aquaculture community who have a vested interest not only financially, but also in food production and ultimately the country’s food security, is either ignored or sidelined, or excluded during the ‘consultation’ process.

In this way, the state has ‘captured’ the entire future of the fledgling aquaculture sector.

Once regulated totally in terms of start-up, species choice, and movement of fish, further state control is expanded to on-farm disease control, harvesting and slaughter procedures, transport of fingerlings, and all facets of the sector that are otherwise self-regulated in traditional agriculture.

It then becomes a simple move to extend this to licences, permits, inspections and restrictions on the agricultural sector as a whole.

More pragmatic approaches

This system of total state control over every sector of the economy has failed in every other country where it had been introduced.

Who stands to gain from this? Certainly not conservation, as the prohibited commercial fish will spread upriver or downstream regardless. If government balanced its restrictive legislation with the establishment of freshwater sanctuaries, it could gain some credibility.

In the current scenario, however, potential investors are driven to neighbouring countries where authorities take a more pragmatic view of aquaculture, and so South Africa falls ever further behind the rest of the global aquaculture community.

South Africa is not an island, yet we have island-based thinking in state-enforced conservation policies.

It may work in cases where fauna can be contained with fences, as is possible with terrestrial fauna.

Buffer zones may also restrict the spread of seeds from noxious plants, for example.

But it is not feasible to adopt different policies for balancing food supply and preservation of species when it comes to major rivers that traverse more than one country.

Mozambique and Zimbabwe’s policies to prioritise food production have meant a wide distribution of alien Nile tilapia in both countries.

These have formed the basis of vibrant tilapia sectors that would never have been viable using low-performing indigenous local species.

This is a lesson that Asia learned 25 years ago. Collectively, farms in these regions now produce hundreds of tons of fresh fish every month for communities that were previously over-exploiting natural fish populations.

The reality is that these fish species have invaded southern Africa’s shared river systems. Without barriers, fish penetrate river systems as far as their environmental tolerances allow.

Despite this reality, the state’s legislative control over the commercial culture of tilapia remains absolute.

The Lowveld region could support large-scale farms using internationally proven methods of bulk tilapia production in areas that no longer hold conservation value for indigenous tilapia.

Restricting production to commercially unproven, high-risk, hi-tech, re-circulating systems on the Highveld, achieves nothing but complete state control.

The subsequent inevitable failure of many of these unviable systems will result in the dumping of fish into natural water sources, negating the desired conservation aim and resulting in a lose/lose situation for all.