Photo: FW Archive

Whether you’re a small-scale or commercial pig farmer, it’s a good idea to think about assembling a first-aid kit for your animals. Keep in mind that you should include your veterinarian in the planning of this first-aid kit, as you’ll need to have on hand a few scheduled medications that have a withdrawal period before an animal can be slaughtered.

READ Using chickens, pigs, and sheep to save your soil

Another important factor to remember is that at least one employee will need to be trained in the use of the kit.

A first-aid kit for humans is compulsory for any business with more than five employees, while a business with more than 10 employees also requires a trained first-aider.

Remember that the loss of even a single animal can reduce the already narrow profit margins in the pork trade.

As mentioned in an earlier article on this subject, a first-aid kit is basically made up of three groups of components. The first includes those medications that need refrigeration and have fairly short expiry dates, such as injectable antibiotics and vaccines.

The second group includes topical wound medications and sprays, as well as eye powders and lubricants that only need to be kept cool. The third incorporates a thermometer, stethoscope and other instruments, as well as syringes (2ml, 5ml, 10ml and 20ml), needles (green, yellow and pink), bandages, cotton wool and sterile gloves, all of which only need to be kept clean and dry.

READ Pig farmers urged to reduce antibiotic use

Each group must be kept in a separate container. A large plastic box that can fit into the fridge is ideal for the injectables and vaccines.

Inspect it monthly to check expiry dates, each time sticking a label onto it that shows the inspection date. The topical sprays and medications can be stored in resealable plastic bags, while the third group can easily be stored in a plastic toolbox.

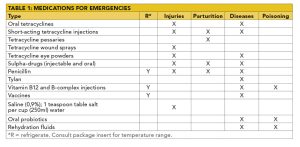

(See Table 1 for the medicines and tools needed to treat common medical emergencies.)

Disease management

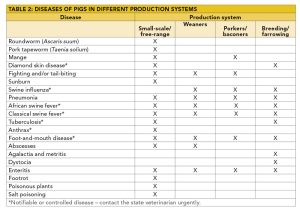

The first consideration when putting together a first-aid kit for your pigs is the number of animals in the herd and the nature of your production system. The following needs to be treated timeously (see Table 2):

- Roundworm. This can be prevented by strategically deworming young piglets and checking faecal egg counts in older free-range pigs, as they can reinfect each other when kept on soil or grass.

- Diamond skin disease is also easily prevented by vaccinating piglets soon after weaning. It occasionally shows in older breeding sows, as they are not usually vaccinated again later in life. Penicillin works very well, if injected early, but you need a prescription for it from your veterinarian.

- Tapeworm infections occur when pigs consume the faeces of infected humans, and they are usually diagnosed at slaughter.

- Mange, caused by mites living on the skin, is easily treated with injectable ivermectin. Fighting and tail-biting are commonly seen when newly weaned pigs are mixed with other pigs. Wash the wounds out well with a saline solution (one teaspoon salt in a cup of water), then treat with a wound spray and inject penicillin.

- Sunburn is often seen in free-range Large White pigs, and zinc ointment works well as a prevention and/or treatment.

- Swine influenza (caused by a strain of the influenza virus) and bacterial pneumonia (usually caused by Mycoplasma spp) are clinically similar. Tylan can be used for both, as bacteria can cause a secondary infection in pigs with swine flu. This drug is available only on prescription, so speak to your vet.

- Both African and classical swine fever are rapidly fatal and, as they are controlled diseases, you’ll have to contact your state vet or animal health technician.

- Tuberculosis (TB) is usually diagnosed at slaughter, but is very rare these days. Where it does occur, it has often been passed on by a TB-infected person who is working with the animals. It can occur as an outbreak in swill-fed pigs, when the swill has emanated from mine canteens, as the mineworkers can become infected with TB while working underground. There is no treatment for pigs.

- Foot-and-mouth disease is also associated with swill feeding, mostly in free-range pigs.

- Anthrax is fairly rare, but can cause deaths in free-range pigs that eat the carcass or meat of an infected animal, or drink contaminated water.

- Abscesses can occur after fighting, or as a result of contamination of the umbilical cord due to an unclean pig pen. A single abscess can be lanced using a sterile scalpel and washed out with saline solution. After this, inject the pig with an antibiotic such as penicillin. Multiple abscesses are not worth treating, as they usually indicate internal abscesses in the liver or lungs; euthanasia is the best option in this case.

- Agalactia-metritis is an acute syndrome in sows, and is often caused by colibacillosis. It requires immediate treatment with anti-inflammatory medications and injectable antibiotics, but is frequently fatal.

- Dystocia refers to difficulty in farrowing. Piglets can get stuck in the birth canal when gilts are overfed in the last few weeks of gestation, as they grow too big. Put on a glove and use lubricant to assist with the delivery, and inject the sow afterwards with an antibiotic.

- Enteritis is fairly common in piglets.Oral antibiotics and rehydration fluids are advised, and the same oral medications indicated for children with diarrhoea can be used.

- Footrot is also fairly common in free-range pigs kept in muddy enclosures. Wash their feet well with clean water, and apply a liberal amount of zinc ointment to the infected areas. They will also require injectable antibiotics.

- Free-range pigs may consume poisonous plants, and the symptoms depend on the plant in question, so it’s a good idea to contact your veterinarian for advice.

- Salt poisoning used to occur when pigs were fed leftover cooked maize from mine canteens; however, I haven’t heard of an outbreak in recent years.

Don’t neglect it!

A first-aid kit should be carefully maintained, kept clean and neat, and checked regularly for expired medicines. It’s also very important to work with your veterinarian when diagnosing and treating the disease.

If you are not the person who usually treats the pigs, make sure the person with access to the first-aid kit is trained to work hygienically and handle its contents correctly.