More people around the world are going hungry, with tens of millions of people having joined the ranks of the chronically undernourished over the past five years.

In the 2020 edition of the ‘State of food security and nutrition in the world’, the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations (FAO) estimates that almost 690 million people went hungry in 2019, which was up by 10 million from 2018, and nearly 60 million in five years.

In addition, the report forecasts, the COVID-19 pandemic could cause about 130 million more people to suffer from chronic hunger across the world by the end of 2020.

The numbers explained

In total, the amount of people suffering from hunger worldwide was revised down from 820 million, as stated in the 2019 report, to the current 690 million.

This 2020 estimate is based on new data on population, food supply and more importantly, new household survey data that enabled the revision of the inequality of food consumption for 13 countries, including China.

Revising the undernourishment estimate for China going back to the year 2000 resulted in a significantly lower number of undernourished people worldwide. This is because China has one-fifth of the global population. Nevertheless, there has been no change in the trend.

Revising the entire hunger series back to the year 2000 yields the same conclusion: after steadily diminishing for decades, chronic hunger slowly began to rise in 2014 and continues to do so.

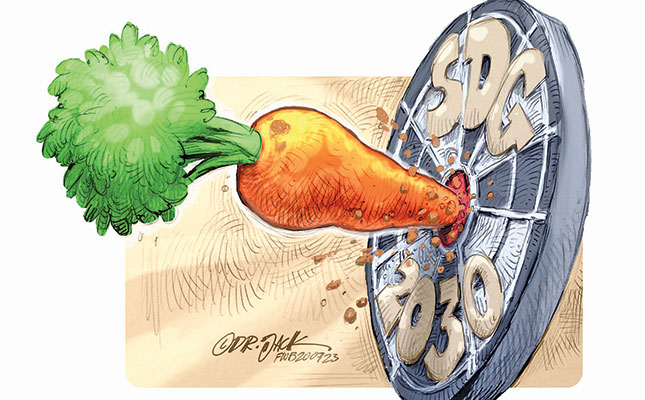

The new estimate for 2019 has revealed that an additional 60 million people have become affected by hunger since 2014. If this trend continues, the number of undernourished people will exceed 840 million by 2030.

As progress in fighting hunger stalls, the COVID-19 pandemic is intensifying the vulnerabilities and inadequacies of global food systems. While it is too soon to assess the full impact of national lockdowns and other containment measures, the report estimates that at a minimum, another 83 million people, and possibly as many as 132 million, may go hungry in 2020 as a result of the economic recession triggered by the pandemic.

Beyond hunger, a growing number of people have had to reduce the quantity and quality of the food they consume. Two billion people, or 25,9% of the global population, experienced hunger or did not have regular access to nutritious and sufficient food in 2019.

Asia remains home to the greatest number of undernourished people (381 million). Africa is second (250 million), followed by Latin America and the Caribbean (48 million). The global prevalence of undernourishment, or overall percentage of hungry people, has changed little at 8,9%, but the absolute numbers have been rising since 2014.

This means that over the last five years, hunger has grown in step with the global population.

This, in turn, hides great regional disparities: in percentage terms, Africa is the hardest hit region and becoming more so, with 19% of its people undernourished. This is more than double the rate in Asia (8,3%) and in Latin America and the Caribbean (7,4%). On current trends, by 2030, Africa will be home to more than half of the world’s chronically hungry.

Food insecurity

Overcoming hunger and malnutrition in all its forms is about more than securing enough food to survive: what people eat, and especially what children eat, must also be nutritious.

A key reason why millions of people around the world suffer from hunger, food insecurity and malnutrition is because they cannot afford healthy diets.

Costly healthy diets are associated with increasing food insecurity and all forms of malnutrition, including stunting, wasting, and obesity.

Food supply disruptions and the lack of income due to the loss of livelihoods and income as a result of COVID-19 means that households across the globe are facing increased difficulties to access nutritious food, and are only making it even more difficult for the poorer and vulnerable populations to have access to healthy diets.

It is unacceptable that, in a world that produces enough food to feed its entire population, more than 1,5 billion people cannot afford a diet that meets the required levels of essential nutrients, and over three billion people cannot even afford the cheapest healthy diet.

In sub-Saharan Africa and Southern Asia, this is the case for 57% of the population; however, no region, including North America and Europe, is spared. Partly as a result, the race to end malnutrition appears compromised.

According to the report, in 2019, between a quarter and a third of children under five (191 million) were stunted or wasted, too short or too thin. Another 38 million under-fives were overweight. Among adults, meanwhile, obesity has become a global pandemic in its own right.

The report presents evidence that a healthy diet costs far more than US$1,90/ day [about R32/day], the international poverty threshold. It puts the price of even the least expensive healthy diet at five times the price of satisfying hunger with starch only.

Nutrient-rich dairy, fruits, vegetables and protein-rich foods (plant and animal-sourced) are the most expensive food groups globally.

A call to action

The report argues that once sustainability considerations are factored in, a global switch to healthy diets would help check the backslide into hunger while delivering enormous savings.

It calculates that such a shift would allow the health costs associated with unhealthy diets, estimated to reach US$ 1,3 trillion [R22 trillion] a year in 2030, to be almost entirely offset; while the diet-related social cost of greenhouse gas emissions, estimated at US$1,7 trillion [R28,6 trillion], could be cut by up to three-quarters.

The report urges a transformation of food systems to reduce the cost of nutritious food and increase the affordability of healthy diets. This means supporting food producers, especially small-scale farmers, to get nutritious food to markets at low cost, making sure people have access to these food markets, and making food supply chains work for vulnerable people.

Clearly, then, we face the challenge of transforming food systems to ensure that no one is constrained by the high prices of nutritious food or the lack of income to afford a healthy diet, while we ensure that food production and consumption contribute to environmental sustainability.

While the specific solutions will differ from country to country, the overall answers lie with interventions along the entire food supply chain, in the food environment, and in the political economy that shapes trade, public expenditure and investment policies.

The study calls on governments to mainstream nutrition in their approaches to agriculture; work to cut cost-escalating factors in the production, storage, transport, distribution and marketing of food, including by reducing inefficiencies and food loss and waste; support local small-scale producers to grow and sell more nutritious food, and secure their access to markets; prioritise children’s nutrition as the category in greatest need; foster behaviour change through education and communication; and embed nutrition in national social protection systems and investment strategies.