Photo: Marinda Louw Coetzee

Hailing from a family of vegetable growers, ‘master grower’ Natie Ferreira looks the part, with his lush beard and hard-working hands. Based in the Boland, Western Cape, Ferreira has been involved in gardening and farming for over two decades.

He has worked in permaculture and biodynamics, and as a landscaper has focused on foodscaping. He has also been growing cannabis for years.

Recently, the Department of Agriculture, Land Reform and Rural Development (agriculture department) issued a three-year permit to Ferreira to grow 8ha of hemp in the Western Cape, at what will now be called the Bien Donné Cannabis Research and Training Centre.

An Agricultural Research Council (ARC) facility, Bien Donné is a historic farm in the Drakenstein Municipality near Paarl, and receives around 800mm of rainfall a year. Part of the farm, and included in Ferreira’s permit, are old fruit orchards, a barn that will be converted into an experimental kitchen and food factory, and 15ha of deep alluvial soil.

The centre will focus on the cultivation of hemp for various uses, including food and fibre. In addition, a number of buildings and open spaces on the farm will be developed to house income-generating facilities such as a deli/restaurant, a dispensary and a nursery.

The many uses of hemp

Hemp has long played an integral part in societies across the world, but its economic

and social potential is yet to be recognised by South Africa’s authorities. Evidence

suggests that it is an ancient crop: remnants of hemp fibre in Chinese pottery can be traced back to 8 000 BCE.

Ancient Hindu and Persian religious texts refer to hemp as ‘Sacred Grass’ or ‘King of Seeds’, and it has been used in common articles such as clothing, rope and paper in many cultures for millennia.

Hemp is a form of cannabis (Cannabis sativa). To be legally classified as hemp in South Africa, the cannabis plant must have a tetrahydrocannabinol (THC) content of less than 0,2%, making it non-psychoactive.

Cannabis is versatile and holds great medicinal, nutritional and economic value. Ferreira emphasises that the uses for the plant extend far beyond its recreational and medicinal applications.

Cannabis in the form of hemp is used to make numerous products, including textiles, building material, cosmetics and biofuel. It can also be used as fresh produce and fodder. Hemp seeds are gluten-free, and have a protein and oil content of 20% to 25% and 25% to 35% respectively. Hemp is also rich in dietary fibre, and vitamins A, B1, B6, B12, C, D and E.

After the extraction of hemp seed oil, the remaining oilcake, containing between 15% and 20% digestible protein, can be ground to a powder for use in foodstuffs. Hemp seed oilcake can also be used as a source of protein in dairy cow and broiler chicken feed.

Oil extracted from the flowers and leaves is rich in cannabidiol (CBD), which has a wide range of medicinal applications that include the treatment of epilepsy, chronic pain and anxiety. In South Africa, however, permits for hemp production do not allow for the harvesting and marketing of CBD as a medicine, as the South African Health Products

Regulatory Authority (SAHPRA) still lists it as a Schedule 4 substance. The seeds selected for future planting at the Bien Donné centre will be determined by the end products, such as food and fibre.

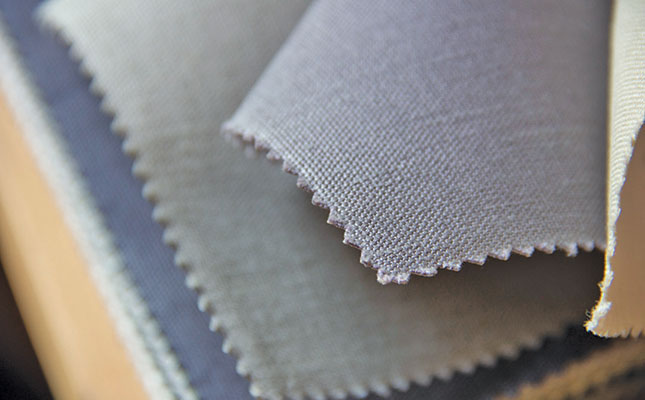

Apart from seeds, the plant produces two types of fibre: bast, fine fibre used to make paper and fabric; and hurd, woody fibre utilised as construction material.

While Ferreira will focus on hemp as a food crop, the fibre of the plant can be used to make items such as hempcrete bricks for construction. It was recently reported that Cape Town is now home to the world’s tallest building (12 storeys) made of hempcrete blocks and hemp building materials.

Cultivation and propagation

Hemp is planted by hand, and production requires irrigation, explains Ferreira. “Planting density varies from one to 250 plants/ m², depending on the cultivar or end use. At Bien Donné, we’re currently planting 30 to 50 plants/m², with an intra-row spacing of between 10cm and 50cm, and 40cm to 120cm between the rows.

“We’ll plant a grain crop in September (to harvest in December) and another hemp crop under lighting in January.”

Pest control is similar to that used on tomatoes. “We farm organically, so we use natural methods and bought-in predatory mites to combat pests. Harvesting and post-harvest processing will also be done by hand.”

Apart from the cultivation of hemp, Ferreira is also permitted to import hemp plants and seeds. He has plans for an on-farm nursery, as the propagation, export and sale of hemp seeds and plants are included in his permit from the agriculture department and authorised under the Plant Improvement Act (PIA).

Ferreira is keen to expand his operations to include a hemp production training facility, and by signing bioprospecting agreements with the local |Xam Bushmen, he hopes to preserve and develop these people’s cultural and ancestral knowledge of various indigenous plants.

The soil and climate at Bien Donné are ideal for incorporating vegetables into a mixed farming concern, and the cultivation and preservation of heritage vegetables and indigenous crops will further diversify the operation.

Research

Joining Ferreira at the new research centre is Moses Mlangeni, the Drakenstein Municipality’s manager of economic growth, and a doctoral candidate at the University of Zululand.

Mlangeni has been involved in cannabis research for years, and is conducting cultivation trials on hemp cultivars grown for fibre. His research involves a hemp cultivation trial, fibre processing, and fabric manufacturing. One of his aims is to estimate the cost of 1m of fabric made of South African-grown hemp fibre. Similarly, he is conducting trials on hemp oil seed cultivars to estimate the cost of a litre of hemp oil.

Mlangeni has been collaborating with Poland’s Institute of Natural Fibers and Medicinal Plants, which is leading the development of the international hemp industry.

“The ARC has also done extensive research on hemp, including the breeding of SA Hemp 1 and SA Hemp 2 seed cultivars,” he says. “Government is heading in the right direction by developing a ‘cannabis master plan’ and issuing research and cultivation permits, but it can learn from Poland. It should allocate more financial resources to the development of the local hemp industry.”

Red tape

The South African government has been widely criticised for its handling of cannabis policies, permits and processes. Prior to October 2021, hemp permits were issued by SAHPRA. Since then, this task has been handled by the agriculture department.

However, there is still much red tape, as well as a lack of synergy between the agriculture, health and justice departments. To cite just one example, the signature of the local police station commander must be included on the permit application forms. This alone added five months to Ferreira’s application process.

To aid the development of South Africa’s hemp industry, the Cannabis Research Institute of South Africa suggests that the legal THC content be increased from 0,2% to 1%, and that cannabis be registered as a crop under the PIA. It has also asked that authorities adhere to stricter timelines to limit delays in the issuing of permits, which subsequently lead to missing the planting season.

Stakeholders and permit holders also believe that government could help to create demand for hemp.

“Government could specify the application of hemp as a building material for the construction of state-funded housing, or the use of hemp fabric for staff uniforms,” suggests Mlangeni.

Despite the fact that government has neither realised the economic value of hemp nor facilitated the growth of the local industry, it seems safe to say that the versatility of hemp will ensure the organic growth of its demand and supply.

Email Natie Ferreira at [email protected], or phone him on 083 578 7619.