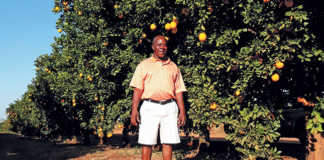

Photo: Glenneis Kriel

Undercover crop production has long been touted as a viable option for uplifting and empowering new farmers.

To date, however, the results achieved have been dismal, with many examples of expensive, government-funded infrastructure being abandoned only months after being erected.

However, Eleanore Swart, who produces tomatoes under cover near Botrivier in the Overberg, is proof that new farmers can achieve success with this highly technical production method.

She was the Western Cape winner of the smallholder category in the Department of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries’ 2014 Female Entrepreneur of the Year Awards.

From student admin to tomato farming

In 2012, Eleanore’s husband, Bryan, received government funding to erect a multi-span greenhouse for tomato production on their 9ha smallholding, Compagniesdrift. At the time, Eleanor was working at Boland College in Stellenbosch as a student administrator.

The following year, after she fell pregnant with their second son, Jeandré, Bryan persuaded her to resign and take over the tomato operation on their farm while he concentrated on his primary business, a sawmill.

“I never imagined myself as a farmer, but taking over the tomatoes presented an opportunity to be my own boss and work more flexible hours,” she recalls.

A factor in Eleanore’s favour was that she had grown up on a farm near Grabouw, where her father had been employed as a farmworker and had kept his own vegetable garden. After leaving school, she had completed a bookkeeping course and had subsequently been employed on the farm to assist in the office.

“These experiences gave me an insight into what is required to be a successful farmer,” she says. “You not only need to work hard and know what you’re doing on the farming side; you also need skills such as the management of people and finances, as well as logistics, business planning and the marketing of produce.”

Eleanore stresses that farmers need to recognise their strengths and weaknesses, and continually work to improve these if they wish to succeed. As she had no practical farming experience, she enrolled in various production courses offered by the Western Cape Department of Agriculture.

Werner Bekker from the chemical supplier, Intelligro, has also assisted her with a fertilisation and pest management programme.

“Werner is always available for advice. He empowers me with knowledge and in effect helps to continually improve my farming skills,” Eleanore says.

The farming operation currently consists of a 3 400m2 multi-span greenhouse divided into sections, each containing about 1 000 tomato plants.

“We try to produce a continuous harvest by planting new tomato seedlings in one of these sections every month. This year, unfortunately, things didn’t go according to plan, as production was disrupted by an outbreak of potato tuber moth [Phthorimaea operculella]. I was forced to destroy all the plants in the greenhouse to eradicate this devastating pest,” she says.

This was the first outbreak of potato tuber moth in the region, and Eleanore has since adapted production to prevent future outbreaks.

Her workers now regularly scout for any damage indicating the presence of these insects, such as yellowing plant leaves. A contact insecticide is also used preventively to combat the pest.

While production suffered a setback, it is recovering slowly, with four sections now planted to tomatoes that will be ready for harvesting in a matter of weeks.

Although Eleanore would ideally like to erect an additional multi-span greenhouse to increase production, the cost of about R1 million per greenhouse has proven prohibitive.

“One of the biggest challenges for small-scale farmers like me is to offer continuous supply volumes throughout the year. This not only has marketing advantages; it also means you’re using your labour force more effectively. Production expansion would also help me to create new employment opportunities,” she explains.

Diversifying out of necessity

To supplement production capacity in the interim, Eleanore has invested in six small tunnels and is planning to add two more later this year.

“I bought the tunnels second-hand from a farmer who retired due to health problems. These are not suitable for tomato production, because they’re not as tall as the multi-span greenhouse we received from the Western Cape Department of Agriculture. So I’m planning to plant green peppers instead,” she says.

After the plants are removed from a section of the greenhouse at the end of their productive livespan, the area is thoroughly cleaned and disinfected.

Plant bags are then prepared by first placing a layer of tree bark at the bottom of each bag to facilitate drainage. The bag is then filled with a growth medium of wood chips.

“You have to clean the planting area thoroughly and use new growth medium to prevent a build-up of harmful organisms that could damage production,” Eleanore explains. “Some producers use the growth medium more than once by rotating the crop or sterilising the medium. Sterilisation is expensive, however, and we have ample access to wood chips from the sawmill.”

A nursery in Stellenbosch produces the tomato seedlings; this enables Eleanore to concentrate on propagating the plants and growing the crop.

Fertigation

Computerised fertigation is carried out according to a formula based on the age of individual plants. On average, young plants receive fertigation three times a day for six minutes at a time in winter.

As the plants mature, and as the weather grows warmer, more applications are added.

“The computer regulates the volume of water and fertiliser that has to be delivered, as well as the timing of these applications,” Eleanore says. “My job as a farmer is in effect to monitor whether these applications take place and to scout for problems.

These could be infrastructural problems, such as broken or poorly positioned irrigation pipes, or growth and production problems caused by pests or other factors, such as nutritional deficiencies or climatic conditions.”

For example, Eleanore has to continually monitor the electrical conductivity (EC) of the water to ascertain its soluble salt content. High concentrations can reduce growth as the ions contributing to high EC could compete with fertiliser nutrients for plant uptake.

Climate control is managed manually by opening or closing doors and tunnel vents. In winter, the vents are closed to raise the inside temperature; in summer they are opened to improve air circulation.

According to Eleanore, tomatoes are usually ready to be harvested three months after planting, but warmer weather can result in the crop ripening up to a month earlier.

As the area tends to experience strong wind, nets have been erected on the sides of the multi-span tunnel to shield it. During a recent violent storm, the farm suffered no damage thanks to early warnings received.

These enabled Eleanore and her team to take extra precautions such as placing tree stumps at the bottom of the windshields as anchors.

Sales & Marketing

Eleanore recently secured a long-term contract with Food Lover’s Market, which will help to reduce her market risks, as prices are fixed for a year and she can deliver tomatoes directly after harvesting them. Demand from the retail outlets that she supplied previously tended to fluctuate. The tomatoes are sorted and packed in a facility on the farm.

To add value to the produce, and to keep workers busy during quieter periods, Eleanore recently started to make jam from second-grade tomatoes. This is sold at farm stalls in the region.

Email Eleanore Swart at [email protected].