The differences between good quality and poor strains are dramatic. Inbred stock develop oversized heads in the males, poor dress-out rates (fillet yield), and females that mature and breed as early as 12cm in length (25g-50g mass), sometimes smaller, and then virtually stop growing.

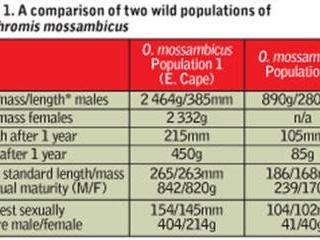

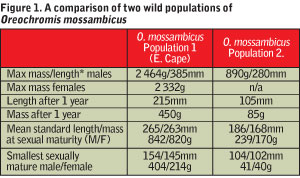

This means expensive feed-pellets are used for reproductive energy, rather than growth, and the fish are so genetically inbred, usually from very small founder populations, that growth beyond about 200g is either unlikely or very slow. On the other hand, good quality strains from the Eastern Cape have deep body shape, even as juveniles, fast growth to 450g in the first year, large-sized females that grow almost as large as males (2 300g for females, 2 400g for males), and cold tolerance.

This makes these strains highly desirable for fish farming compared to the low quality fingerlings so widely distributed at present. Occasional specimens in some wild populations show either partial or (more rarely) a full degree of albinism (xanthic colouration).

This means the fish loses its natural grey/silver colour and becomes orange to red in colour, with females having a yellow chest. Such strains are known as ‘red tilapia’, and are becoming the fish of choice in worldwide tilapia aquaculture due to their greater market acceptance.

They resemble marine fish such as red roman, lack the black skin lining the body cavity and have clean, white flesh. On the fishmonger’s slab they’re far more appealing than wild-coloured tilapia and fetch higher prices. By resembling marine fish, they also tend to allay the perception some people have that freshwater fish are ‘muddy’ to eat, compared to marine fish.

Many strains of red tilapia are used in aquaculture worldwide, but most are Nile tilapia hybrids.

Oreochromis mossambicus eggs hatching in incubator jars prior to sex-reversal under controlled hatchery conditions to produce all-male fingerlings.

In the Eastern Cape, selected strains of wild tilapia are being hatchery-crossed with xanthic blue kurper to produce a faster growing red strain that’s still genetically Oreochromis mossambicus, and therefore permitted for use in local aquaculture by nature conservation authorities.

Alternative

This is an attractive alternative to farming with both poor quality wild-coloured blue kurper, as well as the hybridised, genetically undocumented ‘Nile tilapia’ from the Limpopo catchment. Development of even more improved lines of red tilapia is currently underway by crossing them with the best strains of wild blue kurper from temperate parts of SA, to gain faster growth rates and cold tolerance, and then back-crossing the next generation with red tilapia to regain the orange colour.

All-male fingerlings are becoming available that grow evenly and faster, and avoid the problem of unwanted reproduction in aquaculture ponds or tanks. As with all other forms of agriculture, only the use of the best ‘seed’ or stock available will ensure success. The Chinese have proved this by farming and exporting thousands of tons of genetically improved African tilapia to African countries, that are failing in aquaculture by using poorer quality strains of their indigenous fish species.

Nicholas James is an ichthyologist and hatchery owner. Contact him at [email protected]. Please state ‘Aquaculture’ in the subject line of your email.