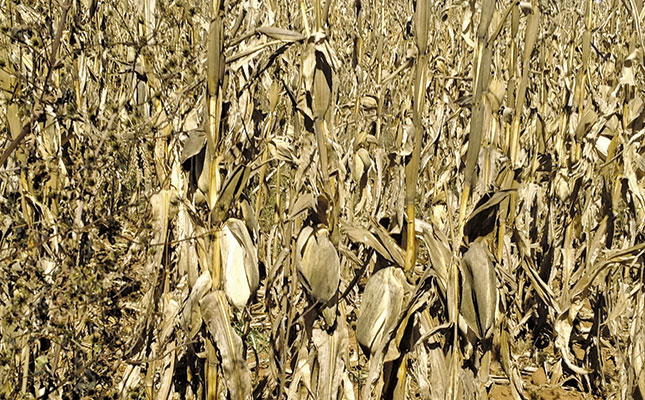

Many maize farmers use horses to clean up the stubble on their lands in winter. This can help owners of pedigree broodmares to make good profit, as the price paid for a pedigree horse is higher than that for a bullock. This year, however, the maize crop was disastrous in many areas due to untimely heavy rains followed by drought and higher-than-normal temperatures in autumn. Some farmers reacted in time, cutting their losses and making silage; others left the mature plants to rot on the lands.

In a Farmer’s Weekly article of 17 April 2015, the Agricultural Research Council described how drought had led to ear rot, caused by Fusarium verticollis, in maize this year.

This fungal infection increases levels of fumonisin, which in turn is associated with equine leukoencephalomalacia (ELEM). The greatest danger for farm horses in South Africa is eating maize stover, rather than concentrates, as quality control is in place for registered horse feeds.

Research into Fumonisin

Prof Theunis Stephanus (Fanie) Kellerman, renowned for his research into mycotoxins and their effect on animals, published a paper in the Onderstepoort Journal of Veterinary Research in 1990 that graphically described the effects of fumonisin in horses.

At that time, vets were puzzled by the cause of equine leukoencephalomalacia. It seemed to be associated with the consumption of mouldy maize kernels, commonly used as a concentrate for farm horses and broodmares. The name of the disease comes from the characteristic ‘holes’ in the white matter of the brain, seen at post-mortem examination of horses that behaved unusually, showing nervous symptoms for a few days or weeks, before dying or being put down.

The disease had been reproduced experimentally by dosing a pure culture of Fusarium moniliformes to horses, so the dangers of feeding mouldy maize to horses was known. Kellerman took the matter further. He found that extracting the mycotoxin fumonisin from cultures and dosing it to horses produced signs of ELEM in the living horse and at post mortem. The two horses in the experiment both showed clinical signs after about three weeks of oral dosing with fumonisin.

Different doses

At a lower dose, the signs exhibited were described as apathy and ‘apparent stupidity’, lack of coordination, a shuffling gait, occasionally stumbling and eventually being unable to eat properly as the lips and tongue appeared to be paralysed. At this stage, the horse was humanely euthanased for post mortem.

At a higher dose, the symptoms were more severe. The horse lost its balance easily and fell, was exceptionally docile and apathetic, walked into objects as if it could not see them, and sometimes stood with its head pressed against the wall. Humane euthanasia was carried out on day 33, as the horse could no longer eat or drink properly.

At post mortem examination, both horses showed ELEM lesions of the brain. Although there were signs of kidney degeneration, no other organs appeared to be affected. Later research carried out using higher doses of fumonisin found liver degeneration. Although blood tests showed some changes in liver enzymes, this was not regarded as an accurate or definitive way of diagnosing ELEM.

Horse owners beware!

The most important lesson for horse owners is that low doses of fumonisin in feed can result in lethal nervous symptoms. As diagnosis is difficult, and treatment is ineffective, the onus is on the owner to prevent ELEM by not feeding mouldy maize kernels or stover to horses, particularly this year, when there is known to be a high risk of ‘ear rot’ caused by fusarium.