Growing up in the 1970s in the then Rhodesia, Hilton Sanders developed an interest in indigenous goat and chicken breeds. This interest was re-ignited when he studied at Cedara College of Agriculture in KwaZulu-Natal in the early 1980s. During his first year at Cedara he bought 10 indigenous veld (‘Zulu’) goats to breed and sell the progeny as an income-generating hobby. Since then, Hilton has farmed indigenous veld goats and Boer goats on and off, an interest he has pursued alongside his professional hunting and outfitting business.

“In 2013 I was sitting in a hunting safari camp in Namibia with friends who shared my passion for goats,” he recalls. “I decided then and there that I wanted to establish an indigenous veld goat stud of the Mbuzi ecotype. I’d already stopped full-time hunting at the end of the 2012 safari season to spend more time with my wife and children.”

Keeping to his intention, Hilton launched the RH Ranching Mbuzi Stud in April 2013. This was by no means the only enterprise that Hilton and his wife Robyn were involved in. Always on the lookout for niche business opportunities, they were already breeding what Hilton describes as “top-notch” riding and trekking mules from Boerperd, Thoroughbred, and American Quarter Horse-type mares put to Spanish jacks, as well as running a fledgling pork-on-pasture enterprise. In 2014, they also started training and selling polo ponies.

While these enterprises clearly have good potential for the Sanders family, they are run on the farms of friends and business partners, some located hundreds of kilometres away. This limits their management and growth potential. It is their hope to buy or lease a single large farm to consolidate all the enterprises and bring them to their full potential.

Potential of the Mbuzi

Currently, the couple run their 105-doe stud Mbuzi flock on Craig and Andrea Truter’s Costa Mint sugarcane, maize and beef farm near Baynesdrift, KZN. Parts of this farm are covered in indigenous valley bushveld, which is ideal for the Mbuzi. Hilton and Robyn chose this ecotype because it has the widest distribution across Southern Africa, despite being the smallest of the four ecotypes found in this region. This results in what Hilton describes as “tremendous genetic variation” in the Mbuzi, allowing a breeder to find genetics best suited to his specific production system and environment.

“These Mbuzi ecotypes are adapted to their very localised environments and conditions, so they may be phenotypically quite distinct. For example, the Makhathini ecotype from the Makhathini Flats in northern Zululand is particularly distinctive, and has a small frame, glossy skin, short hair, very feminine does, distinctive 10-to-2 ear positioning, and a good wedge-shaped body conformation,” Hilton explains.

The Mbuzi thrives in the hot, humid, and tick and pest-infested valley bushveld found in that area, but is equally adaptable to very different environments, even the grasslands of the Drakensberg foothills, he says. “It also has an inherent resistance to heartwater that is endemic to our area and often cripples other livestock enterprises. And it has an amazing ability to convert marginal veld and bush into hard cash.”

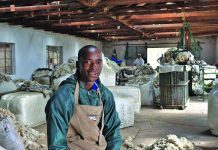

Hilton and Robyn Sanders with two of their children, Ashleigh and Caleb. The couple started their

RH Ranching Mbuzi Stud in 2013.

Doe selection criteria

Hilton and Robyn are still building the numbers and quality of their Mbuzi flock. If they manage to secure their own land, they plan to expand the stud to 500 breeding does. At present, they breed a medium-framed and smooth-coated Mbuzi, avoiding extremes. Selection is done for a very feminine doe with a dainty, pretty face and head, semi-pendulous ears, good jaw alignment, bright and well-placed eyes, an elegant neck that is neither thick nor scrawny, a good topline with sloping rump for ease of kidding, and a well-proportioned chest that can easily accommodate the heart and lungs.

It must also have a good wedge-shaped conformation down to a well-attached udder and well-placed teats. These traits allow for good carrying capacity and feeding multiple kids. “Without exception, we immediately cull any doe with a poorly attached udder or big and bulbous teats,” Hilton says. The front legs must be straight and not bandy or X-shaped. The hooves must be hard and darkly pigmented to enable it to walk long distances on rough terrain while browsing.

While Hilton and Robyn only use horned and not naturally polled bucks as occasionally found with the Mbuzi ecotype, they do not discriminate against naturally polled does, as long as they meet all the other selection criteria. “There’s a school of thought among some of South Africa’s Mbuzi goat breeders that breeding with naturally polled does is undesirable, as these does and their potentially polled offspring wouldn’t be able to protect themselves or their young against predators,” says Hilton.

However, Hilton feels that even horned goats would be unable to fight off larger predators such as leopard and hyena. On the other hand, he has seen impala does, which are never horned, successfully defending their lambs against smaller predators such as jackal and caracal. “We’re not going to deliberately select against polled Mbuzi does, but I’m also not going to throw away a good doe’s genetics simply because she’s naturally polled,” he explains.

Unless a maiden doe has a structural defect, she is put to a buck from the age of about nine months and must produce her first kid by 18 months. Hilton then evaluates the first-kidders’ maternal ability and the quality of their progeny. Any maiden doe or first-kidder not conforming to the Sanders’s strict breeding goals is culled.

“Detailed flock records allow Hilton to make informed breeding and culling management decisions,” Robyn says. “I have absolutely no sentimentality when it comes to doe selection,” Hilton adds. “It’s right or it’s out.” While the Mbuzi is known to be a non-seasonal breeder, the Sanders use three fixed breeding seasons over a 24-month period.

Broad genetic base

“Our stud flock is relatively new,” explains Hilton. “It still has a very broad genetic base sourced from across South Africa, although I personally hand-picked the goats. As the years pass, the flock will become increasingly refined and uniform, in line with our breeding ideals. We currently have enough different bloodlines, so we don’t need to buy in bucks. I’ll only start sourcing outside bucks from reputable Mbuzi stud breeders once it becomes necessary to prevent inbreeding and to add further genetic value to our flock.”

Buck conformation

Hilton and Robyn favour Mbuzi bucks with a well-balanced conformation, a clean scrotum, large even-sized testes, and no split between the two testes in the scrotum. A pizzle well attached neatly against the belly is necessary to avoid picking up thorns, burrs and ticks. “A buck must be very masculine with good capacity and a high libido from a young age,” Hilton stresses. “It must have a bold presence and be darkly pigmented, especially around the eyes, ears, nose and under the tail. We immediately cull any goat with any unpigmented spot on the skin.”

Does that kid in the low fodder-flow months from mid-winter to early spring receive a supplement of dry yellow maize, full grain instead of cracked or milled, to retain vitamins and micro-nutrients. They are fed in the kraals where the goats are housed overnight to prevent stock theft. All goats have year-round access to a lick consisting of dusting sulphur, dolomitic lime, kelp, copper sulphate and coarse salt, supplied on a free-choice ‘cafeteria’ system.

Other nutrients must be obtained from veld grazing. “The bush here is high in protein but lacks energy in winter. Feeding does yellow maize helps them maintain milk production,” he says. The kidding rate is currently 180% per doe mated. Depending on how they have grown out, kids are force-weaned at four to five months to achieve a flock weaning average of about 165% per doe mated.

The flock’s average inter-kidding period (IKP) is 246 days, although some does have achieved IKPs of 173 days, by producing twins. Hilton says that the Mbuzi is “phenomenally fertile”. This high level of fertility and the breed’s multi-coloured appearance, makes it “a lot of fun to breed”. However, he adds that a breeder must be careful not to favour colour over conformation and functionality.

Mbuzi genetic combinations sometimes produce naturally polled does (centre).

Disease resistance

Even the hardy Mbuzi is not immune to some diseases. Hilton and Robyn vaccinate all maiden does for enzootic abortion at five months and give them a booster shot six weeks later. Does are again vaccinated for enzootic abortion four weeks before mating on a two-yearly cycle. Newborn kids’ umbilical cords are trimmed down to 1cm from the navel and sprayed with iodine tincture spray to prevent infection, particularly bacterial arthritis. When the kids are ear-tagged at three days, the punch wound is also sprayed.

At 10 days, all kids receive a Multivax-P Plusto injection to protect them against clostridial diseases such as lamb dysentery, pulpy kidney, tetanus and blackleg. Four weeks before kidding, the entire flock receives Multivax-P Plus injections, which means that the flock receives this vaccination three times in a 24-month period. At four weeks and then eight weeks, the kids are dosed orally against milk tapeworm. At weaning, they are again dosed against milk tapeworm as well as roundworm.

“Every year we deworm the flock early in April and then again in early October to mostly target roundworm and liver fluke. We dip the flock three weeks after the first spring rain to catch the first flush of multi-aged ticks. Thereafter, we only dip the goats if absolutely necessary, based on visual inspection for tick load. Goats should always have some ticks on them – but not too many – to continually challenge their immune systems without overwhelming them,” Hilton says.

Apart from these essential treatments, the goats are treated individually only when absolutely necessary. This approach promotes the Mbuzi’s natural tolerance to pests and diseases. Any goat constantly over-challenged by parasites is culled.

While Hilton and Robyn are building up their Mbuzi flock, they only sell own-bred bucks to other Mbuzi stud breeders and commercial goat farmers.

“In 2014, we sold a total of 15 bucks of 10 months to 12 months out of hand at an average price of R2 500 and market through word-of-mouth and our website,” says Hilton.

Bucks not meeting breeding standards, as well as culled does, are sold to livestock traders.

Phone Hilton Sanders on 072 372 9065, email [email protected], or visit www.rhranching.co.za.