Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Often positioned at the other end of risk, value is regarded as the opposing force, or that desired state of farming operations that can cancel the costs and impact of risk.

To my mind, value creation and risk mitigation are two sides of the same coin of any profitable business.

Many would argue that for as long as the financial value derived from the farming operation outweighs the real and potential risks, a farmer will stay afloat.

My response is that a boat with even a single small hole in its hull is already sinking, perhaps slowly, imperceptibly, but nevertheless its seaworthiness has been compromised. Hidden and/or unmitigated risk is that single hole.

The management of risk mitigation and the seeking of innovative solutions should be aimed at protecting the farmer’s application of time, energy and capital into the future, thereby increasing profitability, growth, sustainability and the security of the farm as a business venture.

A way to protect profit

I propose that the inclusion of the disciplines and skills associated with risk mitigation and management, underpinned by innovative solutions and profitable production management, will better position the farmer to protect profits than a single-minded focus on production and value alone.

Although traditional value chain analysis is a useful management tool, it really focuses on one side of the coin.

An overlay of the value chain of a business, together with the risks associated with each phase of the production process, will prove to be of greater tactical and strategic importance, as it will take full account of the other side of the coin of profitable business.

Analysis of production

As a multidimensional, risk-focused view of a sheep farm, an analysis of the chain of production offers us the opportunity to identify, prioritise and then manage the risks associated with the key areas of value and production.

The ultimate purpose of the risk/value chain overlay is to stimulate the creation and implementation of innovative solutions that will drive the net improvement of profitability.

This is measured finally in rands, but does not exclude improved efficiencies and a range of savings that will all work to underpin better margins in production.

Broadly speaking, in business, a value chain comprises three core elements:

| INPUTS ⇒ PRODUCTIVE ACTIONS ⇒ OUTPUTS |

Inputs can be regarded as the ingredients to be added, and could take the form of intellectual or monetary capital, physical labour or commodities.

Actions or activities might be single events, systems or processes; regardless, the objective is the production or enhancement of value in the form of an output.

Outputs might be in the form of products or outcomes, for example service provision, or in the case of a sheep farmer growing wool, commodities in the form of a certain number of bales of a desired grade of wool to be sold at a targeted and profitable margin by a certain time.

Dynamics of the value chain

Four overarching dynamics form the context of all value chains: time, energy, space and ideas. Of course, these four are also present as inputs, productive actions and outputs.

Each step in the value chain can be measured and adjudicated in terms of its efficient application of these four dynamics.

For example, the selection of a stud ram based on its ability to convert dry feed into body weight, as measured in time and energy costs, would provide a sound indication of whether the capital invested will pay off in its progeny and how long this will take.

Again, we see that each element of the value chain is exposed to risks that will, if left unmitigated and unmanaged, begin destroying the value which the chain of action intends to create.

The rule of thumb in business is: the higher the risk attached, the greater should be the

reward. In the context of this series, this statement raises the question: is sheep farming a high-risk business venture? How does one go about assessing the existing and potential risks of a sheep farm?

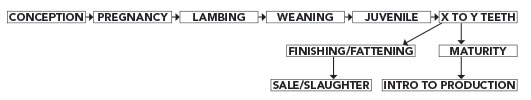

Empirically, we should begin by qualifying and quantifying all dynamics, processes, inputs and pressures having any influence on each production unit, that is the individual sheep. A simplified and generalisable schematic of the value chain of such a production unit is represented in the graphic above.

Each of these elements in the development of the lamb, from conception to the final objective of either being sold or slaughtered, or its introduction as a production unit for breeding or wool, carries risks.

Across all 10 of the value chain elements, core risks are to be found. Consider how the issue of timing affects both the elements of conception and sale or slaughter.

Similarly, it is clear that the functional proof of careful genetic selection of desired traits will be expressed during lambing, but will also be revealed during the finishing/fattening of the animal.

For mutton growers, the 36-month period after the loss of the last milk teeth at age 12 to 18 months, to the eruption of the fifth and sixth front teeth, in other words the chronological age of the sheep from the end of its first year to its fourth birthday, represents the highest risk period in production.

The high costs of insemination, pregnancy, lambing and raising the lamb to yearling status have all been paid for, and the farmer’s patient management is now required for a further three years before any significant return can be expected, particularly if the animal is being raised for its meat.

Variables for shearing

For wool growers, the period is much shorter, as the first profitable shearing most often occurs after the animal’s first birthday (hogget wool), depending on the health and weight of the animal, the quality of the fleece, weather conditions and shearing cycles.

In my schematic of the value chain of a sheep as a production unit, the period of 36 months for mutton growers (that is, sheep at four years old or six teeth), falls within the ‘X to Y teeth’ element.

In the next article, I will focus on this element of the value chain to illustrate the functionality of risk mitigation and management, and innovations for minimising risks.

Email PJ Mommsen at [email protected].