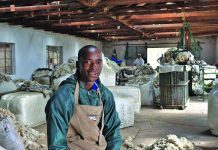

Photo: Landi Groenewald

The Meatmaster originated as a cross between an indigenous fat-tailed breed and European sheep breeds, with the aim of producing a hardy, fertile animal with a carcass that was acceptable at the abattoir.

“This is what attracted me to the Meatmaster, and I have not been disappointed yet,” says René Rossouw, owner of the Jumike Meatmasters stud.

“It is a privilege to work with this outstanding breed but, most of all, it makes economic sense,” she adds.

The farm, Alice, is situated 22km outside Wesselsbron in the direction of Bothaville,

Free State. Rossouw’s husband, Michiel, runs the grain production branch, which is the main component of the farming concern, with Rossouw running the sheep concern as a second source of income.

She describes herself as a perfectionist who manages the stud along very strict rules as far as quality, biosecurity, selection and animal health, among other factors, are concerned.

“I farm intensively, which calls for detailed planning and control. This means constant monitoring and hands-on management. An intensive sheep producer who does not like manure on his or her shoes should rather not consider this type of production system.

“I have spent many hours in the kraal or with the sheep in grazing camps. The sheep are checked and reviewed on a daily basis.

“In a high-density grazing system such as mine, a balance between animal production and the maintenance and improvement of the available grazing is a priority.

“The main focus is on profit per hectare and optimising the production per hectare, so meticulous planning is called for to allow for sufficient days of grazing, recuperation and regrowth,” explains Rossouw.

The farm consists mainly of Avalon soil on which grain is produced. The stud is kept

chiefly on the borderline soils, as well as planted pastures that include sugargraze, oats, hybrid pearl millet and silk forage sorghum.

Two hectares are planted to lucerne meant for baling, while 7ha are planted to soya bean from which Rossouw generates an income used in winter to purchase feed.

The sweetveld grazing camps consist mainly of Smuts finger grass dotted with acacia trees.

Grazing versus planted pastures

Rossouw uses Nemtek sheep and goat netting to keep the animals in a contained area when grazing. The size of the grazing areas is determined by the number of animals put out to graze and making sure the animals have access to enough grazing for a day.

“Because of the intensive nature of my business, it is vital to maintain a fine balance between veld grazing and grazing on planted pastures. The economic realities of livestock production in South Africa, coupled with the mostly extensive farming conditions here, makes keeping animals on planted pastures only a very expensive exercise.”

The flock is rotated daily. One benefit of the rapid rotation programme is a marked reduction in internal parasites.

“One of the cornerstones of my business plan is to supply Meatmasters to the market that are not pampered and are highly adaptable.

“My objective is to market rams that do not need a protracted period to adjust to a new environment.

“It is of utmost importance that my animals adapt as easily to a farming concern in KwaZulu-Natal as they do to a farm in the arid Karoo,” says Rossouw.

Why Meatmasters?

She switched to Meatmasters after the previous sheep breed she farmed did not fare well under the extensive western Free State farming conditions.

“I chose the Meatmaster because, as a composite indigenous breed, it has been developed along economic principles. Because of their disease resistance, resistance to external and internal parasites, and inherent ability to weather extreme drought, I don’t need to pussyfoot around them. For instance, in our area, the bont-legged tick (shiny hyalomma) is a real menace, but the breed’s tick resistance resulted in the bare minimum of infestations.”

Rossouw’s focus is 100% on quality, not quantity. She started the stud with 40 of the best ewes she could afford, acquired from the Sekelbosfontein stud, followed by animals from the Ochre stud in Murraysburg.

During the first year, she bred and used her own rams, but in 2019 she introduced the ram Illovo (JW18.0181) bred by the Mohimba stud in Bloemfontein. That same year, she introduced the Jumike ram 007 (ROS 19.0007) to the flock.

Earlier this year, 007, one of her top rams, was sold to Kroon Meatmasters in Viljoenskroon for R180 000. At the time of going to print, Rossouw was using two Jumike rams and one purchased from Danie Visser Genetics in Namibia.

Adaptability

“Adaptability is one of the most important selection criteria. And for optimum adaptability, optimum rumen health is of the essence. My animals are carefully managed from birth to prevent rumen damage.

“I firmly believe in the saying that livestock producers ‘farm the organisms in the rumens of animals’. Animals that are fed until they’re put up for sale have never had the opportunity to adapt to natural grazing and will inevitably battle to acclimatise to extensive farming conditions. More often than not, overfed rams suffer from rumen problems,” she says.

Ruminant animals, such as sheep, are unique due to the fact that their stomachs contain four compartments: the reticulum, the rumen, the omasum and the abomasum.

The rumen is a large, hollow, muscular organ, filling nearly the entire left side of the abdominal cavity, which develops anatomically in terms of size, structure and microbial activity as a lamb’s diet changes from milk or replacer to dry feed or silage.

“The difference between ruminants and non-ruminants is that ruminants constantly produce saliva. Because of the constant flow of saliva, the pH of ruminants’ rumens become more alkaline. Regular feed intake is important to keep the pH balanced, so I continuously provide the sheep with roughage, even when kraaled.

“A diet high in nutrients and fibre forms the foundation of sustainable production. The importance of top-quality grazing goes without saying,” explains Rossouw.

Genetic potential

Her objective is to supplement her animals’ diet with adequate protein, bypass protein and micro-nutrients coupled with grazing in such a way that the sheep develop their full genetic potential.

Rossouw says bypass proteins such as summer and winter licks are essential in a sheep’s diet. A bypass protein is one that is not digested by the micro-organisms in the rumen and is thus available to the ruminant animal itself for tissue growth or lactation.

It is directly accessible to the animals and does not have to go through the rumination process. The Jumike sheep have access to protein licks in winter and phosphate licks in summer.

One valuable way to keep track of the flock’s rumen health and digestive tracts is to regularly inspect the animals’ dung. It should never be runny, and the droppings should look like pellets without any signs of blood, mucus or a bad odour.

A fall in rumen pH affects an animal in two ways. Firstly, the rumen stops moving, becoming atonic, and damages the absorption area of the stomach. This depresses appetite and production.

“If there’s one thing I’ve learnt, it’s that an animal that ruminates regularly and constantly is a healthy animal. Rumination monitoring is one of the best ways available to a breeder to evaluate and maintain the health of sheep,” says Rossouw.

Animal health

Her commitment to animal health is underscored by a strict hygiene and sanitation regime.

The Jumike animals are kraaled at night.

According to Rossouw, a clean kraal is vital, and the enclosures are therefore cleaned and disinfected on a regular basis. This does not only mean the removal of the top layer of the surface, but also the application of salt and agricultural lime on the exposed subsurface.

The flock is rotated between 14 kraals every three weeks, and salt and lime are applied in the empty kraals. The water troughs and shading in the kraals are thoroughly scrubbed and sterilised regularly.

Rossouw also uses a flock of indigenous Naked Neck chickens to manage fly larvae.

The sheep go through a foot bath and are spray-dipped once a week between October and February to prevent ectoparasites.

Newly acquired rams are kept in quarantine for seven weeks and retested for Brucella ovis by a veterinarian. Rossouw says rams will only be bought for the Jumike stud or sold after a negative test.

The Jumike stud animals are sold out of hand after being selected and judged by official Meatmaster adjudicators. Rossouw finds social media an ideal marketing platform for the stud. Sheep that don’t make the stud grade are sold for slaughtering to a standing client base.

“I gain tremendous satisfaction from the fact that both the stud and commercial animals are marketed directly from the veld without any additional feeding to get them market ready,” she says.

Email René Rossouw at [email protected].