The profitability of a goat enterprise depends largely on the animals’ health and productivity. It is crucial, therefore, that a goat farmer has the skills to identify an animal in poor health, diagnose the illness and treat it, or obtain assistance from other knowledgeable goat farmers, state animal health officials or private vets.

The key is to act swiftly.

READ Buy cattle from a reputable breeder

“While the advice that follows can be helpful, the diagnoses and treatment policies are not carved in stone. They need to be tested and adapted where necessary because of the varying goat production conditions across the country,” cautions Dr Alan Rowe, chief state veterinarian for the Harry Gwala District Municipality.

Prevention is always better than cure, and it is therefore important that any goat introduced to an existing flock be disease-free and healthy. Begin by ensuring that goats always have access to clean drinking water, and enough and the correct quality of grazing, browsing and supplementary feed.

Vaccination programme

Coupled with the requirements above, it is imperative to have a strict vaccination programme to control common diseases, as well as internal and external parasites. Isolate sick goats, so that whatever disease they are suffering from does not spread to healthy animals. Treat every sick goat and keep records of the treatments given.

Animals that are often ill should be culled.

“Weak animals cost money, and may also pass on their weak genetics to offspring,” Rowe explains.

Be aware of common goat diseases – and their symptoms – prevalent in the area, and implement an appropriate preventative vaccination programme. Vaccines are not always 100% effective, however, so animals should be monitored daily, even following vaccinations.

READ Vaccinate your livestock!

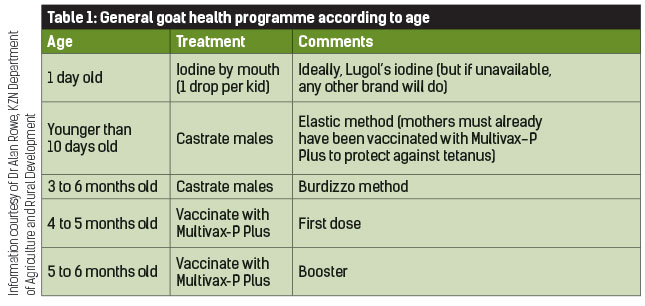

Rowe stresses that goat farmers should administer a combination vaccine against clostridial diseases. These include lamb dysentery, pulpy kidney, tetanus, black quarter, clostridial metritis, blood gut and pasteurella pneumonia.

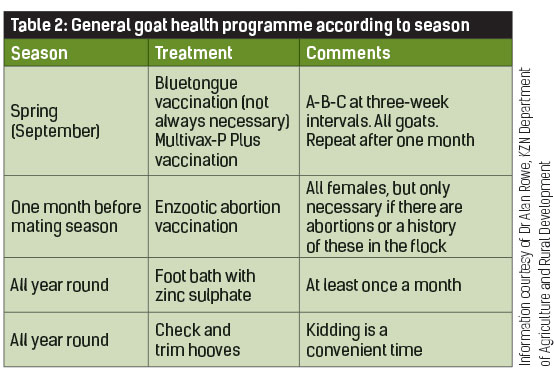

“Multivax-P Plus is ideal for this purpose. Inject it under the skin of the inner thigh when goats are four to five months old and then again one month later. All adult goats should be vaccinated with Multivax-P Plus every year in spring (September) and again one month later. Other vaccinations should be given only if a problem is identified, for example enzootic abortion and goat/sheep brucellosis.”

Essential goat health management products for on-farm use

Information courtesy of Dr Alan Rowe – KwaZulu-Natal agriculture and rural development |

Dealing with worms

Internal parasitic worms are common in goats. Signs of their presence are pale mucous membranes such as the inside of the eyelids, vulva and gums; bottle jaw (swelling under the jaw); decreased appetite; weight loss; poor condition; diarrhoea; sneezing or mucus in the nose; and segments of tapeworm visible in droppings.

Compile a checklist and inspect the animals at least once a month. If some goats are more susceptible to worms than others, consider culling them.

Deworm the flock at least twice a year – in autumn (April) and spring – using products that target roundworm and liver fluke.

“Kids should be dewormed at least once with a product for tapeworm, especially if [fragments] of tapeworm are visible in their droppings. All goats should be treated for nasal worm if they are sneezing a lot, or if worms [maggots] or mucus are observed coming out of the nose,” he adds.

Where possible, deworm only those goats showing signs of worm infestation, not the entire flock. This saves money, and decreases the possibility of worms developing resistance to deworming medication.

“If you don’t know which dewormer to use, seek advice from a local animal health expert. It’s a good idea to alternate the active ingredients in deworming medication to minimise the risk of worms becoming resistant to a particular active ingredient,” says Rowe.

If goats show little improvement after one week of deworming treatment, administer an ultra-broad-spectrum and long-acting (LA) medication, such as Prodose Yellow LA, against liver fluke, conical fluke, nasal worm and roundworm. These medications have a long-acting residual effect against re-infestation, especially against wireworm and hookworm.

“Never use any Ivermectin injectable product that’s not registered for use in goats as some can cause huge swelling and even death,” Rowe warns.

Coccidiosis

Coccidiosis is caused by unhygienic conditions in goat housing or kraals. Older goats can act as coccidiosis carriers, shedding the parasites in their droppings. As young goats are more susceptible to coccidiosis than older animals, they can become infected through these droppings, especially in wet conditions.

Signs of coccidiosis infection include watery or bloody diarrhoea, dehydration, loss of appetite, and loss of general condition.

“Goats infected with coccidiosis must be separated from the rest and treated with Vecoxan (2ml by mouth for every 5kg liveweight), which should be repeated after five days. While it’s the drug of choice, Vecoxan is expensive and sometimes in short supply. A cheaper alternative is Sulphamezathine 16%. On day one, 14ml should be administered by mouth for every 10kg liveweight. On days two and three, the dosages should be reduced to 7ml/10kg liveweight,” Rowe recommends.

A cheaper alternative is Sulphamezathine 16%. On day one, 14ml should be administered by mouth for every 10kg liveweight. On days two and three, the dosages should be reduced to 7ml/10kg liveweight,” Rowe recommends.

Give dehydrated goats a rehydrating solution. These are commercially available, but a homemade solution of half-a-teaspoon of salt and eight teaspoons of sugar mixed thoroughly into 1ℓ of clean water can also be used. Each dehydrated goat should receive 250ml of this solution four times a day for three consecutive days or until you see an improvement.

To reduce the potential of coccidiosis infection, avoid overcrowding the flock in an enclosure. Ideally, the enclosure should have slatted floors to allow droppings to fall through the openings.

Mastitis

Lactating females diagnosed with mastitis should be administered 10ml of a LA oxytetracycline antibiotic, injected into the muscle of the hind leg every third day until cured.

“In severe cases, combine the antibiotic injection with intra-mammary antibiotic medicine for lactating cows. Insert the medicine into the goat’s teat canals once a day after first milking out all milk. Continue this treatment until the mastitis has cleared up,” says Rowe.

Deadly heartwater

Bont ticks can transmit the potentially deadly disease, heartwater, to goats. Find out whether heartwater is common in your local area and implement tick control measures if necessary.

Goats infected with heartwater have high temperatures and manifest nervous symptoms such as abnormal walking, hypersensitivity to touch, falling over and displaying a ‘kicking action.’ Unless treated rapidly, heartwater can result in death. Animals raised in heartwater-prevalent areas are more resistant to the disease, and moving goats not resistant to the disease to a known heartwater area could be risky.

Treat heartwater with a 10ml, short-acting, intravenous oxytetracycline antibiotic injection. It is important to inject directly into the vein, as the heartwater parasite adheres itself to vein walls. “An antibiotic injected intramuscularly takes too long to reach the veins to kill the parasite,” explains Rowe.

Follow up with another 10ml of LA oxytetracycline (preferably), injected intramuscularly. To treat a goat kid for heartwater, inject 3ml to 5ml, depending on its weight, as indicated above. In both cases, if LA is not used, animals should be injected daily for three days.

Foot rot

Foot rot is caused by bacteria, which are easily spread among goats. It is more likely to affect those kept on pasture or under intensive conditions. Minimise its development by keeping sheds clean and, once a week, sending all animals through a foot bath containing a 10% zinc sulphate solution.

Goats should remain in the foot bath for five minutes. If goats become infected, they should be isolated from the rest of the flock until fully healed.

“Goats with foot rot should be injected intramuscularly with an appropriate antibiotic, such as oxytetracycline LA. An iodine foot rot spray should also be applied thoroughly to all four hooves, especially between the hooves,” Rowe says.

Goats can also develop abscesses between their hooves. To prevent these, remove droppings from goat housing at least once a week, dip the animals against ticks, send them through a foot bath once a week, and regularly apply an iodine spray between the hooves.

Treat such abscesses with an LA tetracycline antibiotic injection until healed. For adult goats, the antibiotic dosage is 5ml every third day; for young goats, it is 2ml every third day. Spray the abscesses with an iodine spray until fully healed.

Goats can also develop abscesses under the skin. Once the abscess is soft, cut it open on the lower side with a sterile blade, to allow the pus to drain. Keep the incision open and flush it daily with clean, warm salt water solution to remove any pus. The goat can also be injected with an antibiotic to aid healing.

Rowe stresses the need to wear clean, disposable gloves when treating an abscess to avoid getting infected or causing other animals to become infected.

“The bacteria in the pus is highly contagious and any pus must be carefully collected and immediately disposed of by burying or burning it. The incision should also be sprayed with a wound spray to keep flies away,” he says.

This presentation was given at the 2016 Goat Agribusiness Conference.

Phone Dr Alan Rowe on 079 506 2028/082 855 6138 or email him at [email protected].