It’s 6.30am in early October and Karoo farmer Flippie Loock heads out to feed his Savannah goats. The month-long kidding season is coming to an end and soon all 500 of his ewes will have kidded. In September alone, 400 of the ewes produced 680 kids – including 37 triplets and one quadruplet – and by the time all 500 have kidded, he will have reared approximately 840 kids. This is despite the fact that it has been one of the longest and hardest winters in the Middelburg and Graaff-Reinet districts for many years, with knee-deep snow.

Flippie has not looked back since he started farming Savannah goats using a system he has fine-tuned over the past eight years. “It has turned my farming around,” he says. “I farm on 5 300ha – 3 300ha my own and 2 000ha leased – half of which is mountain veld. It’s rugged, with quite a bit of thornveld, and I was managing to rear only 60% of my Dorper lambs under extensive conditions.

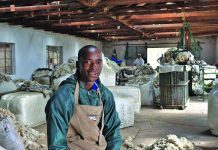

Liesel, Micela and Flippie Loock run several enterprises: goats, sheep, cattle, plains hunting and a guesthouse.

I was farming backwards and facing the same problems that many farmers battle with – predators, absentee neighbours, game farms. So I decided that instead of making excuses for my low lamb crop, I had to find a solution.” At that stage – eight years ago – Flippie had a few goats but admits he did not really know how to farm them. “They were always around the house and in the same camps, kidding year-round,” he recalls.

“Even with small numbers it could get chaotic, with ewes losing their kids. I regarded them as a nuisance until it began to dawn on me that the ideal animal for my veld was right in front of me. Goats are very fertile, with multiple births as the norm. The problem was that I wasn’t managing them.” After deciding to develop a goat enterprise, Flippie did some investigation into the type of goat he wanted.

“I chose the Savannah goat because I like its temperament,” he says. “The ewes have a strong maternal instinct and excellent milk production. I also like them because they’re different and not many farmers have them, so I saw potential to grow the breed.” Flippie sourced his initial stock of 150 ewes from Jansenville and Grahamstown, and his six Savannah rams from John Dell in Grahamstown.

He decided that the optimal reproductive cycle for his situation would be a single breeding season – in April – with the ewes kidding in September. “Our winters are very hard and the condition of the veld during winter isn’t good,” he explains. “I therefore wanted the ewes to rear their kids in summer so I could sell them before winter. This way, I’d only have to look after the mated ewes in winter.”

Camps and management

His initial goal was to kid 100 ewes, so he set up 10 camps of between 0,25ha quarter hectare and 1ha each, putting in 10 ewes per camp shortly before they were due to kid. The camp size depended on the bushes and trees available to shelter the goats from the sun, wind and cold. “This is extremely important,” he stresses. Flippie then set up the identification and management system which has served him well over the past eight years.

Shortly after the ewes kid, he tags each kid with the same colour tag as its dam. “This way, I can assess their condition and ensure, without interfering with them, that they’re bonding,” he explains. Only a handful, such as some of the young ewes with triplets, need extra care, and these are moved onto special camps for this purpose.

Micela and Flippie Loock with two kids in a kidding camp. These animals will be marketed at 6 months to 7 months of age.

During the kidding period, the ewes are given lucerne cubes daily, bought from a supplier in Cradock, as well as farm-grown lucerne once or twice a week. The ewes are fed cubes and lucerne for about 45 days to maintain their condition.

The initial results were so successful that Flippie began building up the flock from his own stock, using white-headed Savannah goat rams.

Within a few years, the number of ewes had increased to their present number – 500 ewes in 52 camps. Today, Flippie breeds and sells his own rams, using the Falkirk Index to identify the best rams and working on a multi-sire breeding flock ratio of five rams to 100 ewes. He weans a 164% kid crop with a birth-to-weaning loss of about 5%, as opposed to 40% in his lamb crop, which he has reduced by 300 ewes to make way for the goats.

The goat ewes stay in the kidding camps for less than two months a year, giving the camps time to recover. “From these, they’re moved to the veld camps to grow out,” Flippie explains. Looking at the ewes and kids at first hand, it is clear they are all in excellent condition. Flippie continues to feed the ewes in the veld camps with the same combination of lucerne cube/lucerne for two to four weeks to help them become acclimatised.

At this stage, the three- and four-week-old kids are also tucking in and by the time the veld starts turning green in mid-October, all 500 ewes and their kids can be run extensively. All the kids are weaned at four months and the ewes are then moved to the mountains for six months until just before they kid again in September.

“I only lose a handful of goats to predators,” says Flippie. “Goats have a natural flocking instinct – they keep in a tight group, whereas sheep tend to wander off alone. In addition, the ewes are aggressive and protect their kids fiercely.” He markets his kids from March, when they are 6 months to 7 months old and weigh 30kg, for about R700 each. Excluding the retained replacement ewes, this brings in about R500 000 before feed costs.

Flippie has done his sums: “Feed costs are about R180 per ewe. I buy in 40t of cubes in August at a cost of R98 000. With a weaning rate of 164%, the food bill equates to selling 130 to 150 kids, which means I can still make 120% per ewe. Compared with 60% in the case of sheep lambs, that’s a substantial difference.” Why does he not apply the same controlled system to his sheep, instead of letting them run extensively?

“They don’t produce nearly as many twins and triplets as the goats do, and it’s this percentage that makes this system economically worthwhile,” he explains. “What’s more, the 164% weaning rate can be increased through selection and genetic improvement.”

Flippie inoculates the goats with Multivax Plus and a straight pulpy kidney injection such as Pulpyvax. He administers Multivax P Plus six weeks before lambing, Pulpyvax two weeks later and Multivax P Plus again two weeks after this. These, of course, are additional costs. “I’m in no way presenting goat farming as a ‘get-rich-quick scheme’, but for farmers in tough conditions like mine, it offers a decent profit if you can cope with feed costs and a zero cash flow until you sell,” says Flippie.

The outlay in creating camps and watering systems is another factor to consider, as is the goat market. “We sell to an agent in Middelburg who markets our goats in KwaZulu-Natal,” he explains. “It’s important that farmers interested in goats work out how to get their animals to market, particularly, as is our case, when they’re far from that market.”

Such has been the interest in his system that Flippie held an information day, hosted by Novartis Animal Health, for 25 Karoo farmers on his farm in September. At the event, Dr Raol Strydom from Camdeboo Veterinary Clinic in Graaff-Reinet gave a presentation on intensive goat management, offering insights into the prevention and treatment of respiratory diseases, diarrhoea and other infectious diseases.

This emphasis on health is echoed by Nibbs Price, Novartis farm animal business manager for the region, who urges farmers to take dung samples and have them analysed, rather than merely dosing routinely. “The aim is to build resilience in your animals. So you must know what you are dosing for and when it’s necessary to do so,” he stresses.

Diversification

In addition to his Savannah goats, Flippie runs 700 Dorper sheep and 100 mixed beef cattle, which he breeds to Brangus bulls. He buys most of these bulls from a local breeder at R15 000 to R20 000 per animal. As a recent innovation, he has introduced Dundee lick to the cattle in winter and a phosphate lick in summer and is “very happy” with the results.

Flippie also operates a game breeding and hunting enterprise – Loock Safaris – which includes several indigenous plains game species and a herd of striking scimitar-horned oryx. “They’re originally from North Africa where they were hunted almost to extinction for their horns,” he explains. He has bred up a strong herd over the years and sells breeding stock to other game breeders, setting some aside as trophies for local and international hunting clients.

The guest cottages (on the right, next to the homestead) cater for hunters as well as overnight B&B visitors.

“We have about eight hunts for South Africans every year, and about five for overseas hunters, mainly from Denmark,”

he adds. His wife Liesel runs a fully catered guesthouse on the farm for the hunters and other visitors. The Loocks’ 11-year-old daughter Micela is no less involved on Springfontein. Determined to become a farmer one day, she already has eight of her own Savannah goat ewes, which produced 14 kids this season.

“I’m breeding up my ewes to 20 so I can sell some to my dad,” she says proudly. For the moment, though, this aspirant farmer is happy to learn from her future client, and assists him whenever she is home from boarding school in Graaff-Reinet.

Contact Flippie Loock on 049 842 1344 or 082 258 0343, or email [email protected].