While waiting for my connecting flight to Botswana, I met a family friend who had recently retired from managing a huge farm operation. Let’s call him Fred. Eagerly I told him I had come back from Germany to do research on improving water-use efficiency in rural rainfed agriculture with an agro-ecological approach.

His response?

“You’re not one of those tree-huggers who wants to save Africa, are you?” And so began the debate between the veteran maize farmer and young researcher with a “not another” European green scheme to save the starving.

Confidently, I threw out a few facts to contextualise sub-Saharan Africa’s food security. Ironically, subsistence farmers produce 90% of our continent’s food supply, yet they make up the majority (50%) of the food insecure population. This is because they have to contend with a host of developmental stresses, including poverty, food insecurity, oil and food price fluctuations, environmental change, rangeland degradation, poor soils and, particularly, drought.

Droughts and floods reduce yields considerably. Additionally, the soils are nutrient deficient with an extremely low water-holding capacity. This doesn’t help when rain is rare and all the water just drains away. As any good maize farmer would, Fred suggested fertiliser and irrigation. But herein lies the misunderstanding. Smallholder farmers can’t afford fertiliser, let alone irrigation, hybrid seeds, pesticides and herbicides. They consume whatever they can grow, without any surplus to improve their situation.

“What about mulching and manure?” was Fred’s next question. “That helps water-holding capacity and soil fertility, and it’s free”. True, but it’s an unrealistic option in semi-arid areas, because mulch and manure are too limited and mulch is more valuable as feed for cattle.

So how do subsistence farmers survive?

A struggle

As most rural farmers are agro-pastoralist, cattle are their main concern. These serve as the household’s savings and buffer in an emergency. The subsistence farmer will go and graze his cattle on communal grazing land. These have become degraded.

Meanwhile, the mother of the household considers the gamble of growing sorghum, cowpea or melons to feed her family. With a 40% chance of failed rains, she’ll lose her complete crop, as well as the time and money that go with it. Not a gamble many people would take.

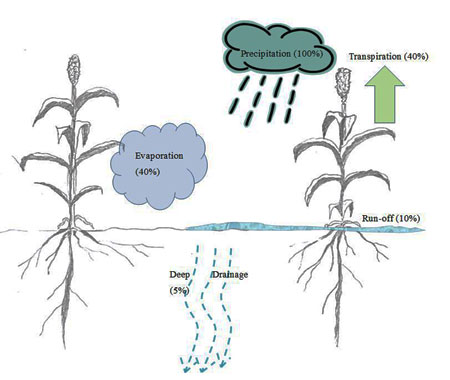

If you audit the rainfall budget of the 300mm of rain that could fall on her 1ha plot over the cropping season, this will give some indication of how much water is actually lost. Depending on factors such as rainfall intensity, slope, soil type and crusting, up to 30% + 40%+ 10% is lost to run-off, evaporation and water draining beyond the root depth respectively.

So, absurdly, up to 80% of the little rain she receives is ultimately lost, leaving little water for transpiration to increase her yield. If she plants, her yield may be as low as 200-300kg/ha of sorghum, as opposed to the rainfed standard of 3-6t/ha.

With Fred looking despondent, I say: “But I have a plan!”

Intercropping

I want to grow strips of forage grass between the crops of sorghum or cowpea. It sounds simple, but it could solve some of these issues. “But I’ve planted forage grass my whole farming life and have fought off grass weeds between my maize,” said Fred. “Grasses will compete with your sorghum or cowpea.”

Well, that’s where my research becomes interesting. Fred’s argument is true. Grasses are fierce competitors and may reduce yields of intercropped sorghum or cowpea. However, an article by S. Sengul (2003) shows a yield advantage of up to 27% per unit area under rainfed conditions with no inputs.

The benefits of intercropping

I think this is partly attributable to the grass intercrop improving the water budget of the whole cropping system. The literature suggests grasses reduce run-off (credit up to 20%); reduce deep drainage (credit up to 10%); shade the soil, reducing evaporation (credit up to 40%); and, finally as a bonus, they reduce erosion. That’s a possible 80% gain if you haven’t been counting.

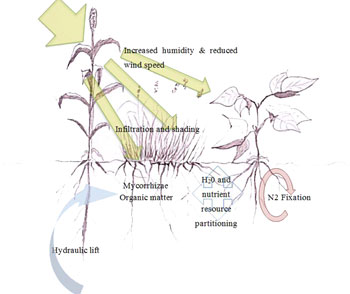

Bigger rainfall events and severe droughts amplify the benefits of the grass strip. If climate change predictions are correct, the benefits will become very significant. This can improve yield stability. Not only that, but a grass strip intercrop acts like a “living mulch”, loosening the soil crust, allowing increased water infiltration and improving conditions for surface roots to access otherwise hard and overheated top soils.

And it doesn’t end there. Adding a grass strip intercrop can improve the microclimate in and around the crop canopy. This means a possible increase in the humidity and a decrease in wind speed around the crop canopy. This buffers the desiccating effect of windy, drier conditions beyond it, reducing unnecessary water transpiration by the crops.

Soils

“OK,” said Fred. “But what about your poor soils? Won’t having another crop reduce the access to the already limited soil nutrients?” This is debatable, and depends on what species you use in your intercropping system. The question also applies to water or sunlight as a limited resource. The idea behind intercropping is that different crops can partition scarce resources by acquiring a resource in a species-specific way or through being competitively strategic in how they access a resource.

Examples include competing crops needing a slightly different profile of nutrients, such as monocots requiring more iron than dicots. Alternatively, crops can have different rooting strategies, such as sorghum extending its rooting depth to find water below the competing crop. Aboveground crops have different radiation requirements. Cowpea, for instance, has a lower tolerance for intense sunlight relative to sorghum, allowing absorption of a greater spectrum of light.

How water is lost

In brief, two different crops use a limited resource more completely and efficiently than one crop would. In the case of legumes fixing nitrogen, the relationship is mutually beneficial. Additional grasses can increase the soil organic matter, improving soil conditions over time.

The concept involves harnessing ecosystem services through integrating your conventional cropping system into the local biome and your farm system. An example would be integrating cattle by using the grass as feed two to three times a season. The additional protein will improve the cattle and possibly reduce pressure on the communal grazing lands.

And with that Fred had to board his plane for his retirement holiday to Europe. And I had to board mine to get started on my research in Gaborone. Hopefully next time I see him I’ll have a few more answers.

* Rohan Orford is conducting his PhD research in Gaborone, Botswana, through the University of Hohenheim, Germany, and the Botswana College of Agriculture. If you would like to contact him about any funding opportunities for his project or to find out more information, please email him at [email protected].