Photo: Numbi Valley

In 2004, when Kathryn Eybers and Ross Dwyer bought Numbi Valley, near De Rust in the Klein Karoo, the soil was so depleted they were told they would never be able to farm anything there.

However, they believed they could transform the land by using permaculture design, and have since turned the farm into a viable operation, working in harmony with nature.

READ You are what your food ate: the health connection in the soil

To understand how, we need to understand Eybers and Dwyer’s background. The couple met during a soil science class while studying BSc Agric at Natal University. Neither came from a farming background, but both had a vision for restoration work.

After majoring in grassland science and entomology they were left with more questions than answers. “Our love for nature made us question conventional agricultural systems. Almost everything was focused on production and hardly anything on ecology or the care of the land,” Eybers says.

After university, in around 1991, they started a small organic vegetable farm near Nelspruit, Mpumalanga.

“Growing organic vegetables was easy thanks to Nelspruit’s fertile soil, but the operation did not work out. I think we were ahead of our time. Consumers did not really know much about organic production back then,” Eybers explains.

“We have come so far since then. Almost everybody understands what organic means these days, which gives me a lot of hope for the future.”

Venture into permaculture

In 2002 they did a three-week permaculture development course with Ewald Viljoen in Zululand, and found themselves resonating with all aspects of the course.

“At university you learn facts, but here the focus was on design and production in harmony with nature.”

Eybers says permaculture design is founded on three ethics. The first, earth care, relates to the restoration and regeneration of depleted and polluted land, water courses and ecosystems, and the rebuilding of nature’s capital.

The second, people care, relates to caring for yourself and helping others, such as your workers, neighbours and community, instead of trampling on others to become successful. The third is fair share.

From an agricultural perspective, fair share relates to how much farmers take from the land for themselves. Instead of getting as much as they can from the land, it implies that something is left for nature and surpluses shared.

Eybers and Dwyer, for instance, only produce crops on 1,5ha of their 70ha farm. The rest is reserved for the wildlife. “When you look after nature, you will have a much healthier ecosystem, and nature in turn, will look after you.”

She does not like the idea of exporting your best to other countries: “In my mind the best should be made available to people in your community and the rest exported. We have always sold locally; most of our produce is sold at markets, restaurants or as boxes around De Rust, which means the sales are direct to the customer. We have also sold produce in Oudtshoorn when we had surpluses.”

Permaculture for Eybers embraces organic, regenerative and biodynamic farming: “Permaculture takes aspects from all of these farming approaches, but is bigger than these because its main focus is on the design of systems to achieve positive outcomes in harmony with nature.”

Numbi Valley

When their organic farm venture failed, Eybers and Dwyer worked for 15 years as bush guides and lodge managers at upmarket lodges all over Southern and East Africa. They had few expenses during this time and managed to save up to buy property.

They wanted to buy a farm on the Garden Route, but could only afford a 4ha plot for the money they were able to pay.

“We wanted to pay cash and not go into debt. Having only 4ha of land did not appeal to us after so many years in the open veld, as you could hear the activities on the neighbouring farms,” Eybers says.

READ Private landowners are vital custodians of biodiversity

The sales agent then took them over the Outeniqua Mountain to Numbi Valley farm. That nigh, they slept on the farm, next to the Olifants River, and the next day decided to buy it.

The farm had very little on it, except for the ruins of an old farmhouse.

They rebuilt it and turned it into a guest house that is rented out to tourists. Then they built their own house from cob, a mixture of clay, sand and straw.

“We attended a cob-building workshop 14 years ago in McGregor with Jill Hogan. She taught us the basics in a weekend. We came home and built our pizza oven, which still makes pizzas 14 years later, and this was a good experience to prepare us for designing and building our cob house. Ross offers cob courses on the farm to share the knowledge.”

Practical application

But how did permaculture help to restore the soil? Eybers explains that they started out by rebuilding soil carbon levels: “From varsity days, we knew that putting carbon, nitrogen and water together would bring back life to the soil. So, we got chaff, as our carbon source, from a local lucerne seed producer, and manure, as our nitrogen source, from a local dairy producer.”

They collected indigenous earthworms from the river that runs through their farm, and mycelium, which is a type of fungus, from the leaf litter of a nearby acacia forest.

READ Lessons in regenerative farming from a visiting US expert

“We were confident that the combination of these components would restore fertility to the soil. The components should be sourced from as near as possible to the farm, as the aim is to create an ecosystem that would naturally occur on your farm.”

During their first year of planting vegetables, everything got sick or eaten up, except for the spinach. The soil started to settle after a year, and they were able to produce disease-free crops after two years.

The vegetables and herbs are produced in circular-shaped growing areas, each measuring 13m2. These circles are arranged over the land to form a mandala, purely for aesthetic purposes.

Eybers points out that the resilience associated with permaculture lies in diversity, so they don’t do companion planting, but complex planting. Hence, a large diversity of plants is planted in each of the growth areas.

“The more diversity you have, the healthier the ecosystem. With a healthy ecosystem, plants are naturally more resilient, but you also have fewer losses because of problem insects or diseases, because these are kept under control by beneficial organisms. When I see a plant with a disease or pest, I don’t remove it but leave it to attract more beneficial organisms,” she explains.

Having such a large diversity is also good from a food security perspective. Eybers explains that she might lose one or two crops in one bed if there has been a disease or pest outbreak, but the specific crop might have survived in other beds.

And, if all these crops were destroyed in all the beds, which is the worst-case scenario, she would still have a whole mixture of other crops left. This would not have been the case in a monoculture system.

Compost and chicken mobiles

Her vegetables are planted directly into compost. “We produce our compost in static heaps, which means that it does not need turning during the decomposition process. To achieve this, we build our heaps in a ratio of one-third dry material, one-third manure and one-third greens from the garden. We put pipes of 80mm diameter that have holes drilled in, all the way down into the compost to improve the aeration,” Eybers explains.

Fruit and vegetables are exchanged for cow or horse dung to use in the compost. She prefers using horse dung because it is higher in carbon than cow dung. Chaff is sourced from the lucerne producer, and all their food waste is added to the compost.

Australorp and a cross between Leghorn and Rhode Island Red hens are sourced at point of lay, from a nearby farm, to help keep the soil fertile.

“I prefer these chickens because they are hardy and good layers. Some of them are six years old and still producing lots of eggs,” she says.

They don’t keep any roosters, as these tend to harass hens when kept in confinement.

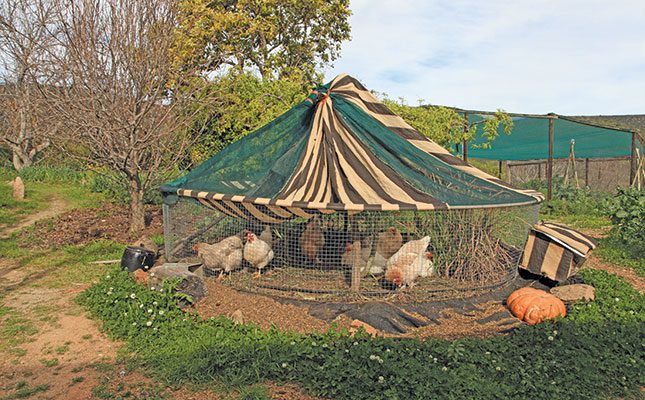

The chickens are kept in two different mobile cages, measuring 13m² each to fit over the plant beds.

READ How compost from Mpumalanga farmer’s bioreactor is boosting no-till crops

The mobiles are moved to a different bed every two weeks. This way the chickens fertilise the soil and get rid of cut worms, mole crickets and other potential pests.

“The chickens thrive under this system as they have access to fresh soil every two weeks, they take lots of dust baths when moved to fresh soil, which helps to control lice and we don’t have to clean out a chicken coop.”

She says the chicken are true gardeners: “Something happens when you put animals on the soil. It is not just like adding manure. They activate the soil with their movements.”

Production

The couple produces a large variety of vegetables, herbs, and fruit and have 1ha under olive trees. The olives are harvested and pressed by De Rustica, after which they bottle it. Their harvest over the past few years has been small because of the drought conditions in the Little Karoo.

Eybers says they used to grow vegetables in the olive orchards while the olive trees were still young, but stopped the practice when the trees grew large as they out-competed the vegetables for sunlight, nutrients and water.

She tried to source as many heirloom seeds as possible when she started the vegetable garden and has since started growing her own seed. The seed is used for cultivating seedlings for new plantings and some of the seed and seedlings are sold as part of the farm income.

“I select seedlings to plant and keep based on their growth in the nursery. I also monitor their growth habit, disease resistance and flavour as the plants mature. This way I aim to strengthen the genetics of the plants that are grown on the farm and the seed I make available to the public.”

Planting is governed by the phases of the moon, because the gravitational pull of the moon affects soil moisture and plant growth, according to Eybers. She explains that leafy plants, such as spinach, basil, parsley and celery, are planted during new moon to first quarter, as plant saps, water and energy are then pulling upwards.

The energy is centred on the middle of the plant during first quarter, so seeded vegetables, such as tomatoes, zucchini, peppers and pumpkins, are planted during this phase, while the planting of root vegetables and fruit trees is reserved for when the energy pulls down – the week following full moon.

The soil is considered barren during the last seven days of the waning moon cycle, which is why this time is allocated to maintenance and tasks other than planting.

Planting by the moon brings structure to her farming activities, she says: “I know what I should plant during each phase and know that failure to plant would result in me not having that crop later. In this way we obtain a constant yield throughout the year, and have enough to sustain us and to sell.”

She adds that she spends an average of two hours gardening each day: “Sometimes I spend a whole day in the garden, and then leave it for a few days before working it again. It all depends on what needs to be done. On the whole, however, the garden and the chickens do most of the work.”

But the question remains whether this type of farming can be financially viable. According to Eybers, it definitely is for them: “We are totally self-sustaining in terms of food, and earn enough to address all our needs by selling surpluses and doing eco-tourism, massages, permaculture farm tours, yoga, cob-building workshops and the sale of organic vegetable and herb seed.”

She adds that their type of farming probably represents the most efficient way of using the land: “We produce food all year round, all season.

Email Kathryn Eybers at [email protected].