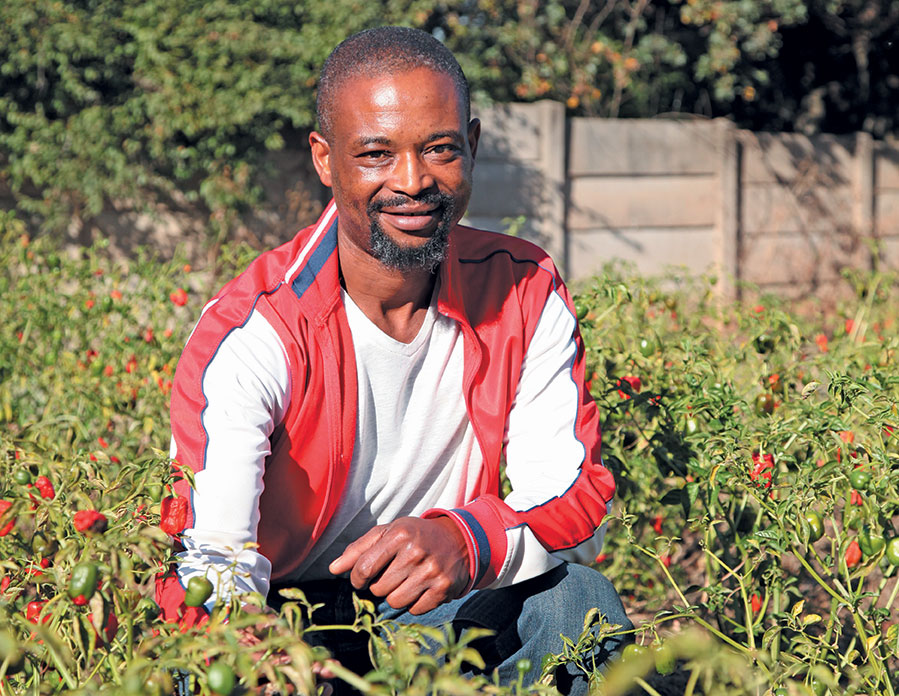

Photo: Gerhard Uys

Clement Tshuma, who produces bird’s eye chillies, spinach, sweet piquant peppers, parsley, onions, serrano chillies and habanero chillies on a 2,5ha agricultural holding near Kempton Park in Gauteng, became a vegetable producer almost by chance.

In short, while working as an air steward for South African Airways, he woke up one morning to find he had been robbed by his gardener.

“He stripped me clean, but left a bottle of chillies. I took the bottle, looked at it, and decided I would start a business with chillies,” Clement says.

He left the airline and began tilling the land on the smallholding. Luck was on his side, he says: “chillies grow like wildfire. You can’t get rid of them even if you try”.

Although Clement has use of the land, he does not own it. He works the soil alone and only employs a part-time worker to assist with some of the digging when required.

However, the rest of the digging, planting, mulching, harvesting and all other aspects of production are carried out by Clement himself, with only the help of his two children during harvesting; an added benefit of being a father, he quips.

He feels strongly about working with, and not against, nature. For example, Clement explains that the last rain before winter not only makes the soil easy to work, but temperatures during that time of the year also makes hard labour more bearable.

Seed production

Key to the success of the operation is propagating his own seed and not replacing plants, such as sweet piquant peppers and chillies annually, contrary to the advice of many seed companies, he says.

According to Clement, the belief that fruit quality declines if plants are not replaced every year has not proven to be true for him, and he has harvested the same quality of produce in consecutive years.

Propagating one’s own seeds and choosing plants that flower biannually also reduce costs substantially.

“Why should [you have] input costs every year. My idea is to have plants that keep reproducing so I can keep harvesting without having to work more. Then I can put the most work into creating new plant beds. In this way you keep moving forward,” he says.

As the seed for the chillies, beans and sweet piquant peppers are propagated on the smallholding, and crops are now sustainably grown from these, seedlings are only needed for the spinach and are bought from three sources: Four Seasons Nursery, Kazimingi Nursery, and CARE, a non-profit organisation and substance abuse treatment facility.

Clement explains that there are advantages to buying plants from all these sources: Four Seasons is cheaper, but plants are clumped together and have to be split, which is labour intensive; seedlings bought from CARE come in trays that make seedlings easier to plant; while Kazimingi sometimes donate plant material that it no longer uses to producers. Seedlings cost about R75/tray of 200.

“You have to spend money on good-quality seedlings. If you make the effort to prepare good beds, you need good seedlings to plant in them,” Clement says.

Mulching

He uses a mixture of grass and horse manure as mulch, and sources grass cuttings from nearby neighbours with large lawns or open lands. Horse manure is sourced from stables in the area. Having access to by-products of this nature near his farming operation is essential to save costs, he says.

Mulching prevents moisture loss and means Clement has an extra day or two between watering sessions.

Currently, around 25% of the beds are under drip irrigation, while he waters some with a sprayer, and others using a furrow system between the beds that he simply fills, with gravity taking care of the rest.

A 1 000ℓ tank on the property is filled with borehole water and about 750ℓ of water is used at a time, with watering done every three days, which is sufficient to keep plants healthy, he explains.

Clement says he ploughs a percentage of all profits back into the operation, to enable him to continually expand his business.

Although he intends buying or leasing additional land at a later stage, he does not believe that receiving a large farm from government is always the best solution for a new farmer.

Farming implements such as tractors are needed to cultivate such a farm, which in itself adds massive costs to an operation, he adds.

On-farm challenges

Frost is a major challenge in the greater Johannesburg area. To address this challenge, shade cloth or plastic coverings that create a greenhouse effect ensure that the spinach crop can be grown throughout winter.

Though his makeshift tunnels do the job, he says he would consider leasing tunnels or the structures for tunnels in the future, as larger tunnels would be easier to work in and allow him to work standing up.

Thus far, one of the main pests that Clement has had to deal with has been aphids on the chillies. He encountered these mainly during the first growing season, but when he began taking better care of the soil, by fertilising and mulching, the problem did not re-occur, Clement explains.

Cutworm, which attack the plants at the base of the stem, is sometimes a challenge for spinach, but he deals with this by examining the plants daily and removing the worms as soon as he notices them.

“I feel the more [time I spend] in the lands, the more of a success I make of production. If I put energy in, everything grows, if I ignore it, it stops. If I’m here every day, I produce more,” Clement says.

Currently, not the entire plot of land is planted to vegetables, but the aim is to extend production and then acquire more land.

Spinach is sold mostly to local restaurants, while serrano and habanero chillies are sold to foreign-owned restaurants where, especially West African customers, have a taste for hot food.

As the chilli crop does not make up a large portion of the entire off-take, Clement says the next step would be adding value through drying and roasting the chillies, which will enable him to access the more lucrative market for processed flakes and powder. Serrano chillies are, however, sold unprocessed.

The restaurateurs whom he supplies, like the fact that they know exactly where the produce comes from, Clement says.

As a dedicated supplier to these establishments, he is also able to keep price increases low, because market fluctuations have a less severe impact on his business, he says.

The ‘vision’

“When I started, I felt I needed to have a project that could benefit those who have land, but cannot afford equipment. I think if someone farms on a small scale, he/she can gradually expand.

The idea is to show people that it is possible to be profitable without needing a tractor and large equipment,” Clement explains.

People in rural areas can establish similar businesses, while the many who are migrating to cities and can’t find work, could also sustain themselves in this way.

“People can grow their own food, as well as cash crops for an income. Government could assist those in rural areas, or even peri-urban areas, to plant [vegetables for this purpose].” It is all about ‘layering’ your farm to unlock maximum potential, he says. “The first layer is sustainability, then cash crops to create revenue, and then adding value, like selling chilli powder, to enter more profitable markets.”

However, the inability to secure loans is a major obstacle for those starting out, he says.

From the outset, Clement’s idea was to start out producing for own consumption, and then slowly build a business from there, without owing anyone any money.

His wish list includes being able to own the land he farms, adding six tunnels and installing an irrigation system, while securing solid distribution channels for his produce.

Email Clement Tshuma at [email protected].