Photo: Candice de Jongh

Staphylococcus aureus (staph) is one of the most difficult mastitis-causing bacteria to eliminate from a dairy herd. Not only is it one of the most damaging and costly diseases of dairy cows, but it’s also very contagious.

For every clinical case of mastitis that’s visible to the naked eye, there can be 20 more cases of subclinical mastitis that can only be identified in a laboratory.

“Subclinical mastitis is responsible for more than 80% of mastitis losses. This is why most farmers vastly underestimate economic losses due to mastitis,” says Onderstepoort udder health expert Prof Inge-Marié Petzer.

A cow with intramammary infection with staph can infect up to seven other cows that are milked with the same unit if the unit is not disinfected in-between the cows. It can be devastating to a farmer, with reported losses of 45% per quarter and 15% per infected cow.

However, staph can be controlled and eradicated from a herd through effective farm management, says Inge-Marié.

“Farmers need to take a proactive approach if they want to overcome staph outbreaks. This includes the early detection of bacteria, achieving optimal parlour management and hygiene, and critically analysing every point within the dairy process,” Ingé-Marie advises.

After several comprehensive field trials in South Africa over the past few years, she believes that the regular StartVac vaccine gives farmers an effective tool in the battle against staph mastitis and in the prevention of blue udder due to E. coli udder infections.

“StartVac aids in the reduction of staph mastitis, but needs to be supported by good parlour and cow management. The benefits increase with prolonged use of the vaccine,” she says.

One long-spanning StartVac field trial, whose results were published in 2020, was initiated in 2014 on two farms. The farms differed in many aspects, but both had staph-positive herds, and both farmers wanted to expand cow numbers and were not keen to cull staph cows.

The trial on Farm 1 was run over seven years from 2014. At the outset, the farmer had 980 cows in milk. The herd was on a total mixed ration (TMR) and was housed in free stall barns with manure bedding, and the farm was located in a winter rainfall area.

Milking took place in a rotary parlour, with parlour care that included pre- and post-milking teat dipping, wearing gloves, back flushing, and a high level of veterinary involvement.

Farm 2 was located in a summer rainfall area, milking approximately 500 cows. The herd was on a camp with a little-shelter TMR system. Cows were milked in a 2×20 point herringbone parlour that had a high level of parlour care, including pre- and post-milking teat dipping, the use of individual paper towels to prevent cross-contamination, and disinfecting gloved hands between each step of the procedure (for example, stripping, wipe, and cluster attachment), and back flushing. There was also less veterinary involvement than on Farm 1.

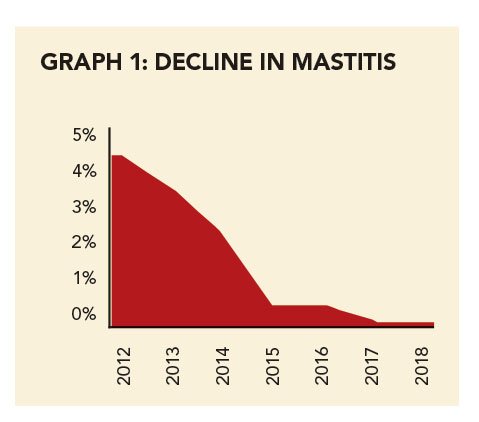

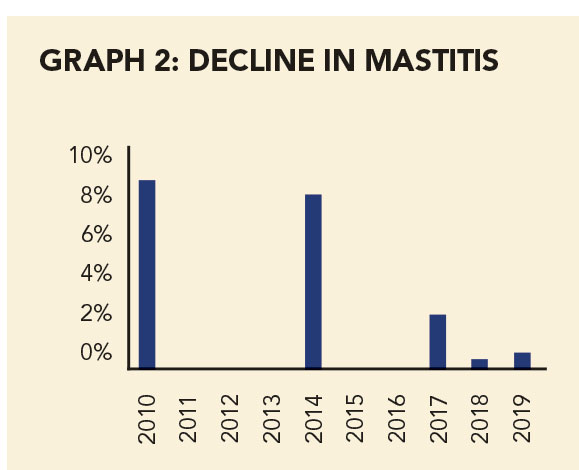

The farms had different management and farming systems, different levels of veterinary involvement, and different climates. Despite this, the trial showed a convincing improvement in the percentage of staph mastitis over time on both farms (see Graphs 1 and 2).

“StartVac played an important role in reducing herd somatic cell count (SCC) and clinical cases of staph mastitis. The cows infected with staph decreased from 4,52% and 8,39% on the two farms to less than 1% at the end of the study periods, despite the herds growing in number,” says Inge-Marié.

S. aureus-positive cows over 10 years on Farm 2. Source: Onderstepoort/HIPRA

“On Farm 1, cows in milk increased from 980 in 2015 to 1 500 in 2019, and the average herd SCC decreased from 655 000 cells/ml in January 2015 to 305 000 cells/ml in December 2019. On Farm 2, the number of cows in milk increased from 500 in January 2015 to 1 000 in December 2019. The average herd SCC decreased over the same period from 449 000 cells/ml to 202 000 cells/ml,” she says.

“Both farms experienced positive economic benefits even during difficult times of drought and political instability. Their milk penalties decreased, herd cow numbers increased while staph mastitis was almost eliminated, showing that the vaccine has a positive effect under different management and farming systems.”

Staph is transmitted from cow to cow in the parlour by milkers’ hands, contaminated communal udder cloths, and in residual milk in teat liners. It can live and multiply on the end of the teat and the surrounding udder skin, but the udder tissue is the main source once infected.

“Staph enters the udder via the teat canal and spreads rapidly. The acute form of staph mastitis is common with a ‘typical’ clinical picture of flaky to watery milk, and a warm, red, swollen and painful udder. It’s not actually different from most clinical mastitis cases.

Staph, however, frequently presents as a recurring, chronic infection that can persist through the lactation and into subsequent lactations. Due to the chronic form, clinical mastitis flare-ups are often seen. The often-fatal peracute form is rare. That’s when the udder becomes bluish, turns cold, and both milk and urine can turn red,” explains Inge-Marié.

Case study of a top herd

One of the top herds tested by Onderstepoort’s Milk Laboratory is Blomfontein in Groot Brak River, owned by Coenraad and Candice de Jongh. The husband-and-wife team placed second in the 2020 Milk Producers’ Organisation/Nedbank Sustainability awards, and they have an excellent udder health programme in place.

In all 14 herd examinations performed by the laboratory over five years, more than 80% of Blomfontein’s lactating cows had an SCC of below 250 000 cells/ml milk.

“Our udder health protocol is aggressive and consistent. We retrain staff once a year and we are [present] at almost every milking. We do composite testing two to three times a year through Onderstepoort, and follow up with quarter sampling on the high-SCC cows. We then either treat or cull, depending on the pathogen and whether they respond to treatment,” explains Candice.

Blomfontein is currently a staph-free herd, but runs StartVac as an annual maintenance vaccine programme.

“Staph is very difficult to eradicate. One of the reasons is that it hides from the body’s defences by living inside the body cells or by producing a mucous around itself.

“StartVac prevents the formation of this biofilm and increases the effectiveness of cows’ immune system.” It also increases the treatment success, as the biofilm no longer protects the staph against antibiotics. In the past, the De Jonghs ran a staph herd according to the guidelines of Inge-Marié.

“Only one handler milks the staph cows. They are milked last and their clusters are not shared with the rest of the herd. After milking, the handler disinfects and the clusters are washed. If these cows are not cured by the recommended antibiotics, they are slowly phased out of the herd.”

The cleaning protocol for the staph-free herd is to pre-dip cows’ teats as they come in; disinfect clusters with an iodine dilution before swinging to another cow; and a post-dip application.

“Dry cows get the same mastitis treatment, but in summer, when flies and heat are bad and they struggle with E. coli damage to the quarters, the treatment is changed to a longer-working dry cow active,” says Candice.

Eradicating staph

To eradicate staph from a herd, says Inge-Marié, three distinct approaches are required:

Good management. This is by far the most important factor not only in preventing new cases of staph, but also in dealing with positive cases.

Treatment. This is almost twice as effective during the dry period as it is during lactation. However, treatment has a limited chance of success and is usually reserved for clinical cases and valuable animals.

Inactivation of incurable quarters and culling. Culling of chronically infected cows is the cornerstone of eliminating staph from a dairy herd.

Success with staph starts with implementing good management.

Up to 30% of humans carry staph in their upper respiratory tracts. Infected people in close contact with dairy cows can transmit it to their udders.

It’s important to test the carrier status of people in close contact with cows. Monitor and limit those who touch the udders.

Milkers should follow good personal hygiene to prevent the spread of bacteria. This includes wearing masks and rubber gloves, and disinfecting hands.

Don’t introduce new animals into the herd without quarter samples. Don’t buy a cow that has tested positive for staph or Streptococcus agalactiae. Improve the biosecurity in your dairy herd.

Improve cow resistance to staph by breeding for traits such as genetic resistance. Milk heifers first to prevent older cows from infecting them. Cows fresh in milk should then be milked and the mastitis group or staph-positive cows last.

Dirty teats must be washed and dried very well. If teats are not visibly dirty, a dry wipe with a disposable paper towel is the best method. Limit the use of water to an absolute minimum.

Always use a strip cup at milking. It supplements the pre-milking stimulation of the milk let-down and prevents over-milking when clusters are attached to the teats. It also flushes out bacteria that colonise the teat keratin between milkings.

A pre-teat dip is thought to be important for the control and prevention of staph. Any open lesion poses a high risk for the multiplication of staph and should be treated immediately.

Never over-milk. This will damage the teat canal and prevent it from closing properly. This creates a permanent highway for bacteria to enter the udder. Effective post-milking teat dipping can reduce new udder infections by contagious organisms by up to 50%. Post-milking teat dip must be applied to cover the bottom two thirds of all teats, because the teat canal stays open for at least 30 minutes after milking.

Back-flushing of cluster units with disinfectant (with a short action) is effective in limiting the spread of staph in a herd. It lowers the bacterial load on the liners, but not on the teat skin.

Prevent damage to teats by ensuring milking machine settings, maintenance and machine use are correct.

Email Prof Inge-Marié Petzer at [email protected].