Photo: FW Archive

This is a tricky time for livestock farmers. Many parasites require heat and moisture to proliferate, and over the past few years, many farming areas of South Africa have had immense rain and elevated temperatures.

Dangerous parasites as well as ticks, which can cause potentially fatal livestock diseases such as redwater and heartwater, enjoy these conditions. In addition, large areas of stagnant water can cause a dramatic increase in disease vectors such as mosquitoes and midges.

Water bodies or drinking troughs showing evidence of mosquito larvae should be drained before refilling. These irritating little insects can transmit serious diseases, such as Rift Valley fever, which can lead to abortion and death in livestock and also be transmitted to humans, causing severe fever-related illness.

READ Diagnosis and treatment of the main livestock diseases

Consider vaccination if you live in areas of South Africa where this disease in livestock is prevalent. There are sporadic outbreaks of Rift Valley fever; the last three were in 1950-1951, 1974-1976 and 2010-2011.

Looking at epidemic trends it appears we may experience an outbreak in the next few years. Empower yourself with information by keeping in regular contact with your local State Veterinary office, which monitors disease outbreaks.

Recent outbreaks of this disease have occurred in the Free State and Northern Cape, but there have also been incidences in the Eastern and Western Cape.

Another vector-borne disease that is specifically dangerous to sheep and often occurs later in summer after heavy rain and elevated environmental temperatures is bluetongue, which also causes fever in animals along with painful lesions of a blue or purple colour in the mouth, gums and throat.

While there are vaccines to counteract the main strains of bluetongue, these have been in short supply over the past few years.

If available, ask for advice as to their use in pregnant animals. Viral diseases such as bluetongue have no special medication protocols because antibiotics are largely ineffective against viruses.

Some old anecdotal remedies or off-label treatments include giving an affected sheep an aspirin dissolved in water, and there are some aspirin-based remedies especially formulated for use in livestock; this assists with counteracting fever caused by the virus.

Antibiotics such as oxytetracycline can be used to prevent secondary bacterial infections that may become a threat due to a compromised immune system.

Do the following for infected animals: place them in quarantine in a dimly lit shed with sufficient drinking water and soft feed, and ensure that the quarters are free of dust. Offer vitamin and mineral supplementation that will assist with supporting the immune system.

READ Lice in livestock: the signs and the treatment

Prevent animals from participating in excessive exercise until visible improvement is seen in their demeanour.

Spray them with a dip to prevent further attack by midges and concentrate particularly on wetting the legs, ears and face of wool sheep. Ensure they do not ingest or inhale dip during application.

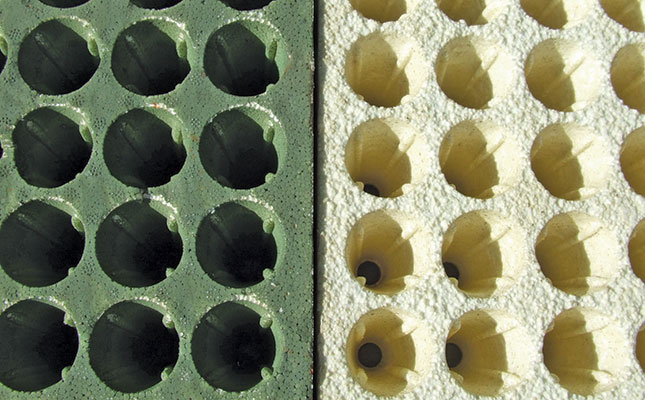

Generally, you need to be proactive at this time of year, when parasite numbers are at a peak. This may involve preparing dip-infused footbaths weekly to counteract some of the ticks gaining access to the body via the legs. However, discard it after treatment to prevent animals from attempting to drink it.

In areas of high parasite infestation, livestock can be sprayed with dip three times monthly. I reiterate that you should target the legs, faces and ears of sheep and Angora goats. But always be careful that run-off doesn’t contaminate water sources.

This spraying will counteract most ectoparasites such as lice, ticks, midges, and mosquitoes.

Where vectors such as mosquitoes and midges aren’t a problem, using pour-on dips every 10 days in peak summer will assist in bringing the tick population under control.

Attempt to drain any non-essential or stagnant water bodies on your property that show the signs of insect larvae, but never attempt to poison these bodies as it will put your livestock and other animals at risk.

I advocate the use of bird-friendly dipping remedies to help develop a holistic pattern of parasite control, as some bird species play an important role in controlling ectoparasites. By conserving birdlife, you are protecting bird species that feed on disease vectors.

Keep recently dipped animals in certain grazing areas for a few days while other grazing areas are kept free of livestock to help break the parasite breeding cycle.

Shane Brody is involved in an outreach programme aimed at transferring skills

to communal farmers.