The COVID-19 pandemic has seen the rapid expansion of e-commerce, online education, digital health and remote work. While these changes can provide huge benefits to communities, they also risk exacerbating and creating inequalities.

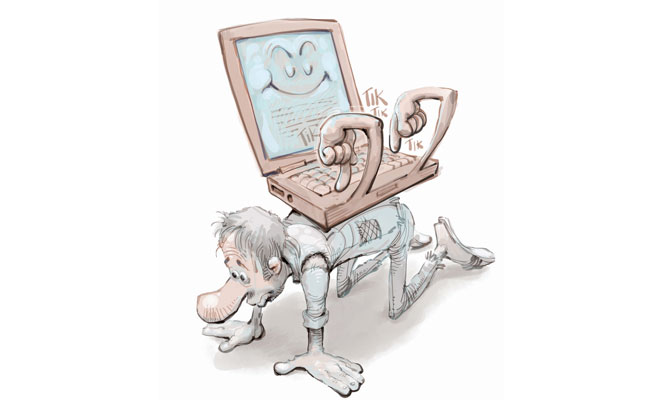

The widening digital gap is in danger of further weakening societal cohesion. Decisions historically made by humans, such as diagnosing health problems, choosing investments and assessing educational achievement, are increasingly made by sophisticated algorithms that apply machine learning to large data sets.

In the private sector, for example, more businesses worldwide are turning to algorithmic management to track employee productivity. Automating these decisions deepens biases when they depend on algorithms developed using skewed historical data sets.

The risks of automating bias are exacerbated by the volume of data currently generated, and this amount is predicted to nearly quadruple by 2025. Moreover, the volume of data drives down the cost and ease of using algorithms for malicious or manipulative purposes.

Individuals and non-state groups all have access to algorithms that can spread dangerous content with unprecedented efficiency, speed and reach. It is becoming easier to launch misinformation campaigns on a national and global scale. And, because individuals and small groups are difficult to track and prosecute, it has become harder for authorities to stop the spread of misinformation.

Fissures in digital equality are exacerbated by political and geopolitical incentives. Some governments shut down Internet access to control the flow of information and public discourse within their borders, or to exclude foreign-based platforms.

The UN has called on “all governments to immediately end any and all blanket Internet and telecommunication shutdowns”.

Government inaction

In countries where stark interventions are not a threat, government inaction has created risks to citizens. While nearly four-fifths of countries have implemented regulations on e-commerce and data protection, government responses continue to be outpaced by the speed of digitalisation.

Governments need to narrow the regulatory gap widened by new digital resources and technology’s growing influence over human interactions, or risk digital public goods concentrating in private actors.

Automation was already reshaping labour markets before the arrival of COVID-19, but the pandemic led to an economic crisis and a digital leap that shrank budgets and time frames needed to retrain workers. The World Economic Forum’s (WEF) ‘Future of Jobs’ report estimates that automation may displace 85 million jobs in only five years.

In developed and emerging economies alike, the rapid shift to remote working is expected to yield long-term productivity gains, but it risks creating new gaps between ‘knowledge workers’ and those in hands-on sectors who cannot work remotely and may lack the digital skills and tools to find other employment in areas such as manufacturing and retail.

Such expansion requires significant investment in upskilling and reskilling. However, public spending and policymaking capacity to reduce the digital skills gap will be limited after COVID-19, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Vulnerable workers, particularly in the informal sector, where 60% of the world’s workforce finds employment, and where livelihoods were hit hard by the COVID-19 crisis, will most likely need to prioritise keeping their existing jobs over dedicating time and money to training.

Regulatory backlash

Societies are becoming more disconnected. Populations find themselves increasingly polarised and bombarded with misinformation. A regulatory backlash to combat this outcome risks further disconnecting societies.

Widespread falsehoods and conspiracy theories hinder civic debate and consensus on critical political, public health and environmental issues. ‘Infodemics’ surrounding COVID- 19, for example, have impeded efforts to stem the physical damage from the disease.

Misinformation could endanger a global recovery that hinges on widespread vaccination.

More broadly, disinformation and misinformation campaigns can erode community trust in science, threaten governability and tear the social fabric. According to the World Economic Forum’s Global Risks Perception Survey, the backlash against science will heighten the risks of climate action failure and infectious diseases over the next decade.

The World Health Organization warns that ‘post-truth’ politics, from deliberate manipulation campaigns to the spread of conspiracy theories and fake news, are “amplifying hate speech; heightening the risk of conflict, violence and human rights violations; and threatening long-term prospects for advancing democracy”.

Yet blunt government attempts to combat misinformation can worsen the problem. Internet restrictions, for example, risk excluding entire societies from the global information economy, while more invasive control could infringe civil liberties.

User disenfranchisement

Power is becoming more concentrated in markets such as online retail, online payments and communication services. This could confine political and societal discourse to a limited number of platforms that have the capability of filtering information and further reducing the already limited control of individuals over how their data is used.

Stretched budgets will limit consumers’ options as they choose digital services and providers that best suit their new needs. Lack of competition between providers by way of offering stricter data privacy policies could prevent users from gaining more control over how their data is collected, used and monetised.

Users and consumers could also lose the power to negotiate or revoke the use and storage of data they have already shared, willingly or unwillingly.

Increasingly, users will be at risk of exposure to targeted political manipulation, invasion of privacy, cybercrime, financial loss, and psychological or physical harm.

Regulations are tightening around providers’ responsibility for illegal activities on their platforms, such as the spread of misinformation and malicious content. A regulatory ‘techlash’ could confront major tech companies with large fines, along with more government control and the possibility of breaking them up.

Stronger government intervention in digital markets could empower consumers and users by fostering more competition and regulating anticompetitive practices. On the other hand, breaking up major platforms could also reduce services to many people. Without platform benefits, smaller companies may not be able to reach less profitable markets, which would widen digital inequality.

The context, fairness and governance underpinning the digital leap will determine whether the adoption of new technologies advances individual and societal well-being or widens the gap between the technological ‘haves’ and ‘have-nots’.

Rising to the challenge

Ensuring a smooth digital transition and mitigating the risks to social cohesion from digital divides will require managing innovation without stifling it, for example by insisting on security and privacy being built into new technologies and digital services.

Basic education and lifelong learning can increase digital literacy and play a critical role in closing digital divides. But increasing access to digital content is not enough; as machine-learning and biotechnology evolve, new users need to think critically about the supply and consumption of digital content.

The WEF’s ‘Future of Jobs Report’ shows that the digital leap has already propelled worker appetite for online learning and training on digital skills such as data analysis, computer science and information technology.

Employers have also risen to the challenge; during the second quarter of 2020, employer provision of online learning opportunities increased fivefold. Similar opportunities exist in leveraging digital services to overcome existing and emerging inequalities in health accessibility, affordability and quality.

Digital tools will benefit workers and employers alike; two-thirds of employers

expect to see a return on investment in upskilling and reskilling within a year, while enhanced healthcare reduces business risks.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

This article is an edited extract taken from the World Economic Forum’s ‘Global Risks Report 2021, 16th Edition’, published in January 2021.