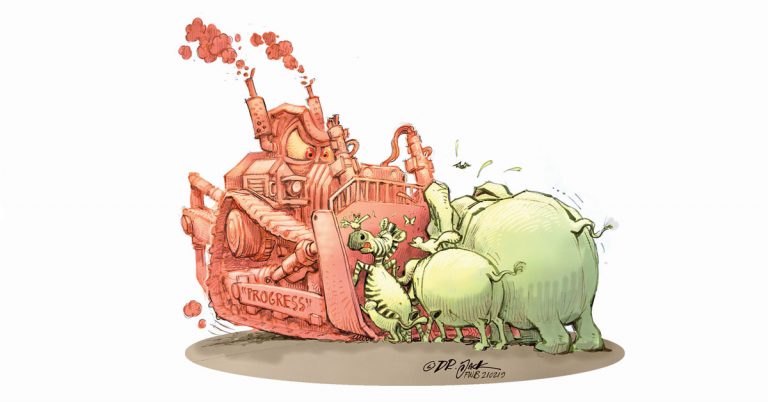

As the world emerges from the health and economic crises caused by COVID-19, it faces converging and compounding environmental crises: climate change and the accelerating destruction of nature.

Although its benefits are often hidden, nature sustains over half of the global economy: it ensures food security and supports water cycles; it protects communities from floods, fires and disease; and it helps mitigate climate change by absorbing carbon dioxide and, in some cases, providing resilience against the effects of climate change.

But this stock of natural assets is finite and dwindling. The need for action is pressing: 32% of the world’s forests have been destroyed, 40% of invertebrate pollinators face extinction, and there has been a 23% reduction in land surface productivity due to land degradation.

This drawdown on natural capital is accelerating climate change, decreasing resiliency, and

reducing the availability of fresh water, clean air, fertile soil and biodiversity. Meanwhile, climate change is having a substantial impact across the world.

Rising temperatures, disrupted water supplies and flooding are set to displace millions of people. While there are tens of millions of environmental migrants today, approximately one billion people will live in countries that do not have the resilience to deal with expected ecological changes by 2050.

Involving nature

Natural climate solutions (NCS), which are conservation, restoration and improved land

management actions to increase carbon storage and/or avoid greenhouse gas emissions, have the potential to address the converging crises of climate change and nature loss.

At the same time, they could help deliver sustainable development in line with the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, which aim to provide equitable livelihoods, advance education and equality, and improve natural resource management.

The private sector

Private sector commitment to climate action is gaining momentum. Many companies are setting net-zero goals to drive low-carbon strategies and address the risks and opportunities they face.

Physical risks include disrupted supply chains and volatile prices of raw materials resulting from extreme weather events and other climate effects, as well as regulatory and reputational (transition) risks that arise through shifts to greener economies.

Their customers, meanwhile, are demanding climate-friendly products and services, and

companies seen as failing to act face a potential loss of business.

Investors, too, are demanding action, and the call is being heard:

- net-zero commitments by companies have more than doubled in the past year, and the scale of NCS within these commitments is rising accordingly. Based on net-zero

commitments today from more than 700 of the world’s largest companies, there have already been commitments of about 0,2Gt carbon dioxide (CO2) in carbon credits by 2030.

Today, those making net-zero claims are expected to reduce their emissions where possible, and neutralise by retiring an equivalent amount of carbon credits or investing directly in carbon removals.

Investing in nature

There is no clear path to deliver climate mitigation without investing in nature. Limiting

climate change to safe levels requires avoidance or reduction of emissions, and removal or

sequestration of CO2 from the atmosphere.

While exact estimates vary based on climate mitigation pathway modelling, if we are to reach a 1,5°C or 2°C pathway by 2030, we require a 50% net emission reduction of about 23Gt CO2 by that date from 2019 levels. NCS could deliver up to one-third of this net emission reduction.

What makes investments in nature especially attractive if done well is the enormous and varied array of ‘co-benefits’ that can arise alongside the direct actions taken to address the biodiversity and climate crises.

These include heightened resilience in the face of the negative effects of climate change,

and more sustainable development opportunities for local communities. Improving soil health, for example, increases the resilience of croplands, while fire management can mitigate the risk of catastrophic wildfires.

Both can help protect and secure the income and assets of rural communities. Therefore, upscaling NCS and addressing the causes of the historic underinvestment in nature solutions will help close the biodiversity finance gap, recently estimated at between

$722 billion (about R10,8 trillion) and $967 billion (R14,4 trillion) per year over the next 10 years.

A scale-up of NCS could also provide important innovation and learning opportunities for the transition to a nature-positive food and land-use sector, a critical task for world governments in the next decade.

Beyond the environmental co-benefits, NCS projects can create broader benefits for local

livelihoods, health and education. As the bulk of low-cost NCS potential is in the Global South, NCS projects can generate flows of private capital to these countries. This creates further co-benefits, even those not related to nature or climate, such as reduced inequalities.

Analysis carried out by the Woodwell Climate Research Center for this report shows that the three largest NCS by potential have high environmental co-benefits, including sequestering carbon, biodiversity, soil health and water quality. The table indicates the importance of particular NCS on these co-benefits.

Carbon markets

While there is tremendous potential for NCS as part of a net-zero economy, a number of technical and conceptual hurdles, institutional failures and poor experiences of past schemes have created a lack of confidence among many stakeholders about how effective NCS can be.

This has prevented NCS markets from achieving scale. In the past, carbon markets in general and forestry credits in particular have suffered from low price levels, an oversupply of credits as a result of inflated baselines, insufficient demand, and liquidity on the market.

These technical hurdles can be overcome with improved monitoring technology and market

architecture. Perhaps most importantly, the conceptual differences that hamper today’s market development require stronger collaboration and dedicated efforts to build effective institutions and trust among both public and private actors, but also between the resource-rich host countries of NCS projects and potential buyers of such credits.

Carbon markets present one opportunity to increase financing for NCS and help them reach the scale required to meet net-zero targets.

Other financing vehicles that have gained increasing attention include debt-for-nature swaps, green bonds and loan programmes, blended finance instruments to de-risk investments, and nature-linked insurance mechanisms to increase resilience.

While not the focus of this report, it is recommended that further work be undertaken to see how these other types of vehicles, together with carbon markets, can provide a portfolio of NCS financing solutions.

The message of this report is that several key actions must be taken to overcome existing bottlenecks in NCS carbon markets and create certainty for buyers, suppliers and regulators.

The views expressed in our weekly opinion piece do not necessarily reflect those of Farmer’s Weekly.

This article is an edited extract taken from the ’Consultation: Nature and Net Zero’ report released by the World Economic Forum in January 2021.