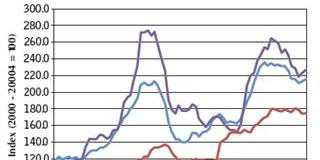

The current sharp decrease in the value of the rand is the third since 1996. Various factors influence the value of a currency in the long term, such as interest rates and inflation. The International Monetary Fund estimates that inflation in South Africa during 2013/2014 will be 5,8% and 5,5%, while US inflation over the same period is expected to be 1,7% and 1,8%. This means that we’ll see a long-term decrease in the value of the rand.

In the short-term, the factors mentioned play a lesser role. The rand fell to its lowest level in four years on Tuesday 11 June. Commentators blamed this on diverse factors such as the weakening of the Australian dollar. But the over-reaching reason is a loss of confidence in South Africa’s economy. The outlook for the rand remains uncertain and highly volatile. Historically, a sharp decrease in the exchange rate is followed by a period of recovery. But the long-term trend will remain downwards.

The impact of a weaker rand on farmers will depend on several factors.If, for example, the rand weakens against the dollar, but not the euro, this will result in higher prices in the US and not the European markets. The problem, then, for farmers who export to Euro-land, is that the bulk of their inputs, such as fertiliser, pesticides and packaging materials, are based on raw materials traded in US dollars.

Exporting industries and those affected by imported products benefit from a weaker rand. While dairy product prices on international markets decreased from the record levels of May 2013, the weakening of the rand resulted in higher rand-based prices and thus in higher import parity. This has already led to higher prices for maize and other grain on SA markets.

But modern agriculture uses high-technology imported products and the prices of these are also directly linked to the US dollar. Farmers will pay more for fuel, fertiliser, chemicals and machinery and equipment. However, as imports are usually planned well in advance and with forward cover on the exchange rates, input prices do not usually increase immediately.

A weaker rand holds the danger of higher interest rates, as the Reserve Bank can increase the repo rate if inflation exceeds its 6% top limit.

Higher interest rates will then, theoretically, discourage expenditure and lead to lower demand. They may also increase the attractiveness of an investment in rands. However, the Reserve Bank’s repo rate is already 4,7 percentage points higher than the US rate. Thus, higher interest rates may not strengthen the rand.

Managing input costs

While a weaker rand will result in higher product prices for exporting and import-prone industries, it’ll also mean higher input costs. Farmers will have to manage these carefully. Agribusinesses are quick to increase prices as soon as the rand weakens. In most cases, old stock acquired at a more favourable exchange rate is then sold for more. Buying groups can play a major role in keeping prices down.

Major input suppliers try to differentiate their products from the similar or nearly identical products sold by their opposition with screeds of semi-scientific information. However, whether urea is bought from Company A or Company B, it will be identical, or effectively so, as will high-protein concentrate from feed manufacturers C and D. Farmers should not let high-powered advertising fool them. All of these products are manufactured to minimum legal standards, and in most cases the cheapest product is the best buy.

Input prices, especially of products such as fertiliser, are cyclical. Therefore farmers can, for example, save substantially by buying fertiliser in bulk before the planting season and not during the season. The weaker rand will increase farmers’ gross income. Careful management of their procurement policies will help them to keep a part of this increased gross income for themselves.

Dr Koos Coetzee is an agricultural economist at the MPO. All opinions expressed are his own and do not reflect MPO policy. Contact Dr Coetzee at [email protected]. Please state ‘Global farming’ in the subject line.