Photo: Lindi Botha

Fourth-generation farmer Jan Grey inherited a diversified farming business when he took up the running of the Janvos Landgoed farm in Mpumalanga’s Bethal area.

However, continuing with the mix of activities has never been set in stone, and choosing what to pursue and what to exclude from the operation are factors that Grey must constantly and carefully weigh up to ensure the success of the business.

Having been at the helm of Janvos Landgoed for the past 30 years, Grey has overseen its transition from a casually diversified farm to an enterprise where each division has a specific purpose.

“When I was growing up, farms had a bit of everything – there were a few chickens, a couple of ducks, and a patch of maize. It was more of a lifestyle than a specialised business. But today, it’s a highly focused industry that needs to be run exactly right, or there’s no place for you on a farm,” says Grey.

“It’s very easy to go bankrupt in farming. Those who continue to make a success of it are truly remarkable and they are farming big, well and right. There are so many challenges facing farmers in South Africa, and they need to be at the top of their games to keep succeeding,” he adds.

In 1994, when Grey joined his father Vos on the farm, Janvos comprised a small dairy, a Merino sheep stud and commercial herd, a commercial cattle herd, and grain crops. Grey increased the size of the dairy and boosted the technology therein, and added a Boran cattle stud, grass-seed production and an apple orchard.

“It’s not easy to expand and it takes blood and sweat,” he admits. “It requires capital, more management and greater risk. But if you want to keep farming, you are forced to expand, otherwise the business will become unprofitable.

“An agricultural economist once said that farms need to grow by 3% each year – either in size, efficacy or turnover – or they won’t make it because of the rising costs. That’s why you need to keep looking at ways to manage costs and inputs more effectively. You’re either part of the race, or you must leave it.”

Division Management

Grey takes care to invest in capable people who will take ownership of their particular divisions.

“My biggest investment is in people. I look for those who are passionate about what they do, because that makes their jobs easier. Even if they don’t have all the knowledge, their passion will motivate them to learn.

“Providing employees with up-to-date training is crucial, as we need to keep pace with the latest tech and innovations, and know what’s going on in the industry,” he says.

“Being part of organised agriculture is important because I believe that we, as farmers, are stronger when we stand together. I might not be able to get to all the meetings, but I always make sure that I’m represented.

He notes that good workers are widely available in the countryside, especially since so many youngsters travel to the US to work on farms, but then return to South Africa to settle down.

“They come back with knowledge and experience. Our South African boys are good, strong farmers. There are many who want to farm but don’t have land, and giving such people an opportunity helps all of us.”

Janvos has 77 permanent workers, and each division has its own manager and cost centre.

There is no cross-subsidisation of the divisions, and if one division wants to use another’s equipment, they must hire it, not borrow it.

The livestock division, for instance, buys its hay bales from the grain division. The machines work for everyone, but the division that pays for a tractor hires it out to the others, for example. And the grain division sells its product to the dairy for feed.

Spreading risk

Each division is managed as if it were a business on its own, thereby ensuring that Grey has a clear understanding of which ones are profitable and which are not. It takes time and great care to decide whether to maintain, grow or scrap a particular division.

“You can’t make a short-term, emotional decision about what to farm and what not to farm, because farming has its ups and downs, and this is all part of a natural cycle of events.

“If there is a downward trend over time, I must decide whether to adapt or die – either the division will be culled or I will find new and innovative ways to make it more profitable,” says Grey.

He explains the importance of diversification: “Diversification spreads risk because you don’t have all your eggs in one basket. We can do both extensive and intensive farming, as the latter boosts our profit/ha.

“Therefore, we milk intensively and do intensive farming of high-value fruit like apples. Diversification also assists with cash flow.”

In the grain division, Grey spreads his risk by planting one-third of the fields to conventional maize, one-third to Roundup Ready Maize and one-third to soya bean. They also practise conservation agriculture and minimal tillage. Choosing to go this route and preserve the soil was one of the best decisions Grey has ever made for the farm, since he believes in taking responsibility for the land he occupies.

He notes that the divisions should complement one another, rather than compete for resources. “The sheep don’t compete with the cattle, as they can pick up the small maize kernels that the cattle can’t.

“So while you can keep 100 cattle or 100 sheep, you can keep far more than 100 of either if you have both, as they utilise the fields differently.

“By having soya bean and maize, I spread my risk across two crops and I can fully utilise my implements. The residues also serve as additional food sources for the livestock,” explains Grey.

“The dairy provides daily cash flow, and since the industry is stable, I can plan far in advance. The apples provide a big income from a very small piece of land. We also reach the market earlier than the rest of South Africa does, and we’re among the earliest to reach the market in the Southern Hemisphere, so we have a price advantage.”

Out with the old

Janvos eliminated its sheep division in March this year, having fallen prey to Grey’s philosophy: if it pays, it stays. The farm was, for many years, renowned for its Merino stud, run by Vos. With his father’s passing last year, Grey decided to remove this division from the farm.

“My father was very passionate about the stud and he gave it a lot of attention. Without him, we don’t have the passion and expertise to keep it at the high level that he did, so I believe it was better to sell it.

“The high incidence of sheep theft also influenced my decision. The losses were so big that it just wasn’t worth it to farm sheep anymore. The continual theft also has a negative impact on your morale, and it is soul-destroying to put so much into something, only for it to be stolen from you.”

The Boran stud was the most recent division included in the operation, having been registered in 2008, and adds value on a small piece of land.

“A commercial bull and a stud bull eat the same amount of food and require the same amount of space. However, you make considerably more from the stud bull. It does require extra admin and registration fees, but it boosts your value per hectare,” explains Grey.

Apple farming was added to the mix in 1998, at a time when the rand had weakened considerably against the US dollar. This export product now helps the farm increase its earnings through foreign income, thereby acting as a buffer against the depreciation of the local currency.

Apple production also complements the other activities on the farm, since harvesting takes place during the first few months of the year, when the other divisions have slowed down.

Five different cultivars are grown across 30ha, all under nets to guard against hail damage. The fruit is packed at Hi-Veld Fruit Packers in Ermelo, in which Grey is a shareholder, and it is distributed locally and internationally.

Go big or go home

Three years ago, the economics of milking forced Grey to have to choose between either expanding his dairy division to better utilise economies of scale, or scrapping it altogether.

“Milking cows also takes a lot of effort. It’s not the easiest activity on the farm and profitability is under pressure. The fact that [the number of] dairy farmers is dwindling is definitely proof that profitability is shrinking. The cost-price squeeze is rampant, and you are forced to expand your dairy to increase production to make your investment in new technology worthwhile.”

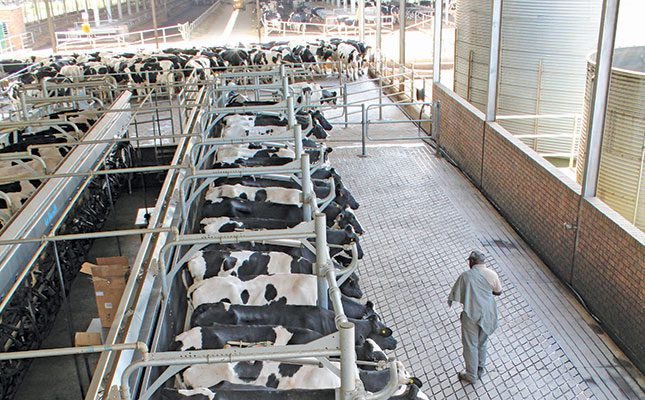

Since the dairy industry has traditionally provided stable returns, Grey decided to double the milking parlour’s capacity and install new technology to optimise cow comfort and therefore milk yield.

The parlour now has a 50-point rapid-exit system that allows for the milking of 1 000 cows three times a day. The Holstein herd currently comprises 700 cows in milk, and Grey is in the process of expanding the herd to match the full capacity of the system.

This new technology focused on cow comfort has paid off, as Grey has increased his milk yield from between 18ℓ and 24ℓ/cow/day to between 34ℓ and 39ℓ/cow/day.

“Research has shown that cow comfort has a big impact on milk production. The quicker a cow can go lie down, get comfortable and start eating after milking, the better, as both the milk yield and butterfat [content] increase.

“A cow whose feet are sore, struggles to find a place to lie down and is uncomfortable registers a drop in milk production,” he explains.

Milking under a roof has also made a big difference, since the cows are kept cooler in summer and out of the rain and mud.

“Cows are very sensitive to heat. On a hot day, there is an 11°C difference in temperature between standing in the sun and under the roof, and this impacts milk production,”he says.

Challenges and opportunities

A generator is used to power the milking parlour, providing a constant reminder of the challenges that farmers face with load-shedding.

“Milking becomes incredibly expensive if you need a generator to power your system. Also, as our irrigation is scheduled for 24 hours a day, if we only have power for half of the day, then we’re only 50% effective. The crops dry out in this heat if they go without water.

“We’re also left to our own devices when it comes to the things that government should be providing. We are completely at the mercy of livestock thieves and other criminals. I also have to maintain the municipal roads around the farm myself at a huge expense, or I can’t transport my produce and my employees can’t get to work.

“It takes months to receive VAT [refunds] from government, which has a big impact on cash flow.”

Still, Grey wouldn’t want to be anywhere else. “From a young age, I never doubted that I would farm. There is still a lot of potential and many opportunities for farmers in South Africa if we can just keep improving our productivity.”

That’s why he embraces new technology, which he believes is a sure-fire way to be more effective and ensure sustainability.

As we walk around the farm, it’s clear that technology is prevalent here – a drone hovers above a soya bean field, applying crop-protection chemicals that a tractor would otherwise be unable to, considering how wet the lands are at present.

The drone also sprays with more precision than a spray cart or aeroplane can, as it is able get into difficult-to-reach parts of the field. Grey says that, in future, drones will be used to count livestock and guard against stock theft.

The farm’s tractors are fitted with precision technology systems that help to reduce input wastage. For example, autosteer leads to a saving on diesel, because it makes the tractors work more accurately.

Long-term averages in maize production have also risen as a result of new technology, with yields growing from 3,5t/ha to 7t/ha.

Grey’s willingness to embrace new technology stems from his assumption that there is always something new to learn and improve upon, and that one must never give up on the quest to do better. “There are a lot of challenges in farming, but we must fight to find the best way forward,” he says.

Email Jan Grey at [email protected].