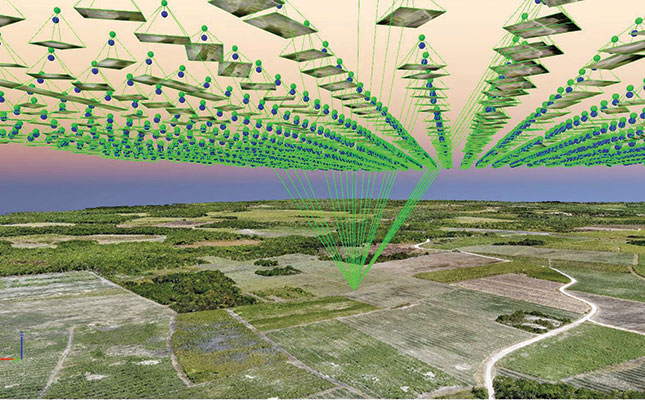

Photo: Agri-Sense International

In its six-year existence, Agri-Sense International, which is based in Hilton, KwaZulu-Natal, has used its unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) to digitally map more than 500 000ha in 13 countries.

This includes the world’s largest topographical survey ever undertaken by drones: 106 000ha in 106 flights over 28 days in Belize in Central America.

And in a more recent survey in Ghana, the company used two UAVs to map 36 000ha, a process that required 80 hours of flight time.

Conducting surveys on this scale is impressive enough, but it is what the company does with the data that is perhaps more important.

Agri-Sense has two core functions, says managing director Russell Longhurst:

- The use of UAVs to collect the data required to generate detailed digital terrain models

for clients, especially for the further development of agricultural land; - Monitoring crop health and productivity using near-infrared (NIR) camera technology and then generating a normalised difference vegetation index (NDVI).

“Commercially available satellite imagery has its uses, but is often not as precise and detailed as imagery collected by UAVs flying only a few hundred metres above the ground,” explains Longhurst.

Better sensors

The company currently owns two Sky-Watch Cumulus C1 fixed-wing drones and five

multi-rotor DJI Phantom 4 Pro UAVs for its land surveying and crop monitoring operations.

“The Sky-Watch Cumulus gives us far less blurring of the images captured and can also be equipped with better sensors,” says Longhurst.

The imagery captured by the UAVs is converted into 3D digital maps. These allow Agri-Sense’s clients to precisely calculate any of a wide variety of agricultural design needs.

For example, the data can help with the layout of farm roads and contours; the location and shape of croplands; matching agricultural production to terrain; the location and availability of water resources; the design and layout of irrigation systems; and siting farm buildings and other infrastructure.

In short, it can provide a full agricultural land-use plan.

In addition, as noted, UAV-mounted NIR cameras can generate data essential for monitoring crop health, thereby allowing a farmer to tackle a problem before it spreads across the entire farm.

One of the advantages of an NIR-capable UAV is that it can cover an entire cropland, including areas that farmers and farmworkers cannot see from ground level. In this way, the sites of potential problems can be recorded precisely.

Getting started

Mike Cohen, a geographic information system and photogrammetry specialist at Agri-Sense, says the process of planning and getting UAVs ready for survey work is elaborate and time-consuming. (Simply put, photogrammetry is the science of making measurements from photographs.)

To maximise the quality of the imagery to be generated, the Agri-Sense team must first digitally mark ground control points (GCPs), which can number in the hundreds depending on area size.

Using global positioning system technology, the team also designates a virtual border or ‘geofence’ around the area, which ensures that the UAV flies only within these limits. The cameras on the drones are capable of taking images of 1cm- to 10cm-pixel resolution from an altitude of up to 360m.

“To make the 3D digital maps even more accurate, we use stereophotogrammetry techniques that take 14 images from different angles of a single point on the ground,” says Cohen.

“In an area of 10 000ha, we’ll take about 8 000 images that our software will take three to five days of processing to stitch together to generate a detailed digital topographical map.”

As with most aspects of agribusiness, economies of scale play a significant role in the costs of having land or crops surveyed by UAVs. Simply put, the larger the area being surveyed, the more cost-effective it is for the client.

In some instances it is more economically feasible for farmers to buy their own UAVs to survey for crop health, and then use a third-party company (such as Agri-Sense) to process and analyse the data, says Longhurst.

The cost per hectare for Agri-Sense’s full services includes moving the team and the equipment to and from the survey area, the flying time on site, and the ground control, which is essential for generating accurate data.

Once the GCPs have been established and measured and the area to be surveyed ‘bordered’, Agri-Sense launches its UAVs to fly the designated routes autonomously.

The battery powering each UAV can keep the drone aloft for up to two hours. When its power runs low, the UAV automatically returns to the ground control base, where it is fitted with a freshly charged battery. The drone then takes the most direct route to the point where it left off and continues its survey.

Agri-Sense has become particularly expert in surveying areas ranging from 5 000ha to 30 000ha, notes Longhurst.

Using the data

The data gathered and processed by companies like Agri-Sense is of little use if clients cannot access it readily whenever and wherever they need to.

To cater for this, the company has developed Agri-Sense maps. Clients have password-controlled access to the digital platform via computers, tablets and mobile phones, and they can also opt to give a contractor, such as an irrigation erection company, partial or full access to information on Agri-Sense Maps.

If there are many smallholder landowners in an area, they can form a co-op that can ‘pool’ the parcels to create a larger block to be surveyed. Mapping by UAVs can be used to determine the precise location, shape and extent of each smallholder’s land, and how it fits into the co-operative farm.

Additional information, such as the name and a photograph of the landowner, is captured using Agri-Sense’s Data Sense system and attached to the data for each field. This is then automatically synced to Agri-Sense Maps for ease of access and use.

This imagery and other information allow for the design and layout of the most efficient farming infrastructure for the co-op, and also determines the percentage landownership a single smallholder has in the overall area of the co-op farm for the purposes of profit-sharing or rental income.

Coming soon

The existing capabilities of Agri-Sense’s UAVs, cameras and products are remarkable. But the equipment is set to become even better, given the scope and potential of newer technologies constantly being developed for UAVs, says Longhurst.

One such development is UAV-mounted cameras capable of hyperspectral imaging (HI), which provides even greater detail to maps.

Once requiring large, delicate and expensive laboratory equipment, HI is the process of capturing and producing an image at a very large number of wavelengths, explains Techbriefs.com.

Whereas multispectral imaging might evaluate an image in three or four colours (red, green, blue and near-infrared, for example), HI imaging breaks the image down into tens or hundreds of colours. Its resolution and colour sensitivity enables the viewer to pinpoint a bruise on someone’s arm!

A second development is UAVs capable of spraying crops with agricultural chemicals.

Even more precise

“Bringing remote-sensing and spray drones together will complete the precision agricultural cycle, enabling the farmer to easily find the problem areas and target them to avoid unnecessary blanket spraying of the crop,” says Longhurst.

Contact Agri-Sense International at 072 537 3451 or [email protected]. Website: agrisenseinternational.com