Photo: John Deere

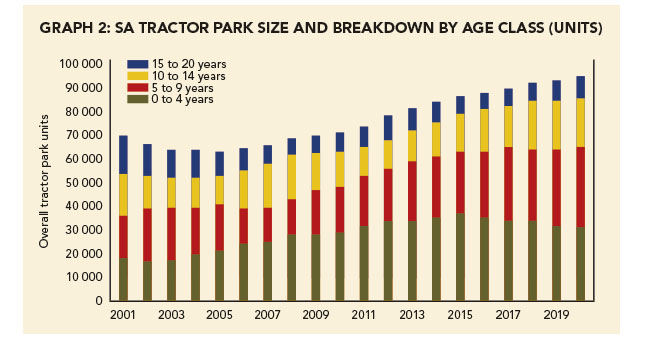

Since 2000, South Africa’s tractor park, which is an estimate of how many of these agricultural machines there are in the country in any given year, grew from 75 276 units to 93 020 units by the end of 2020.

These estimates were compiled and published by AGFACTS, a local company specialising in analysing and reporting on trends in major capital agricultural machines and implements, and are an important indicator of how South Africa’s commercial farming operations are faring financially.

AGFACTS’ founder and chief executive, Dr Jim Rankin, who is also the secretary of the South African Agricultural Machinery Association, says this indicator is especially true of national new tractor sales that, by annual total value alone, represent approximately 60% of South Africa’s total agricultural machinery market.

“A farmer may buy a particular new agricultural machine to do a specific job. The farmer may also buy a new machine to replace an older one that has been doing a particular job.

“When the country’s agriculture sector is doing well, farmers have the money to buy new machines. Farmers also use purchases of new agricultural machines as a way to take advantage of the legally permissible opportunity to pay less tax,” Rankin explains.

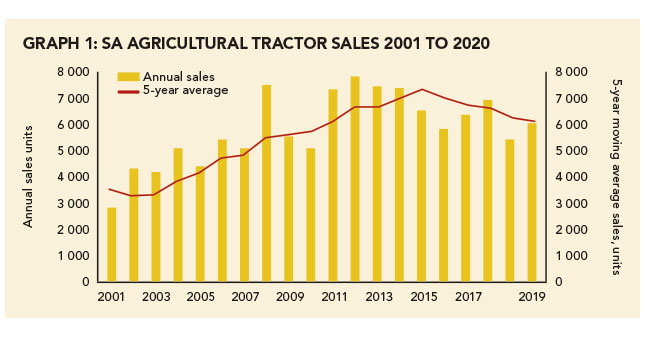

Paul Makube, senior agricultural economist at FNB Agribusiness, says that motivating perceptions that new agricultural machinery sales are an indicator of sentiment and economics in South African commercial agriculture in a given year is the fact that during the country’s recent nationwide drought of three consecutive years, when commercial farmers were “forced to tap into their own reserves to cover their capital obligations”, activity in the new agricultural machinery sales market “flattened” (see Graph 1).

However, as the drought subsequently broke for much of the country, especially towards the end of 2020, FNB Agribusiness experienced a definite increase in its financing of new agricultural machinery purchases.

Imported machines change the landscape

Writing in various monthly AGFACTS Newsbriefs, Rankin said that while South Africa’s new tractor sales in years immediately preceding 1981 were commonly around 15 000 units annually, various factors had contributed to a gradual, but significant, reduction in annual sales figures since then.

Much of this change began in 1993 when the South African government, based solely on commercial motives, chose to repeal a long-time law requiring only South African-made engines to be fitted to new tractors sold in the country up to then.

A major result of this law was that the average tractive power of South Africa’s tractors, measured in kilowatts, had been relatively low compared with many other regions of the world at that time.

For the 10 years from 1983 to 1992, the average engine power of new tractors sold was 58,2kW. Having access only to less powerful tractors meant that the country’s farmers typically needed to buy and operate more units of these to effectively complete all of a farm’s tractor-required activities.

“The average power output of new tractors surged after 1993 when foreign-made engines were allowed to be imported. The five-year moving average power of tractors in the overall South African tractor park has increased from 72kW in 2000 […] to 76,1kW currently,” Rankin says.

AGFACTS statistics show that in 2000, the collective tractive power of all units in South Africa’s tractor park stood at 4,8 million kilowatts. At the end of 2020, this figure had grown significantly to 7,2 million kilowatts.

Makube says that technological advances and their commercial availability had “definitely” changed the local market for agricultural machinery in recent years, and that South Africa’s commercial farmers were increasingly utilising these technologies to drive efficiencies and profitability in their operations.

“South African commercial farmers are price-takers and not price-makers and, therefore, the only way to counter production inflation is to work smarter and reduce costs. We’ve seen increasing demand for […] especially technologically advanced equipment that is already precision-farming-ready,” explains Makube.

Corné Louw, a senior economist at Grain SA, says that to the best of his knowledge, the country’s grains and oilseeds production sector arguably collectively owns and operates the largest portion of the national tractor park (see Graph 2).

He says that this is because the production of these crops is extensive across South Africa and, by its nature, increasingly requires bigger and more efficient machinery and implements to keep the relevant farming operations profitable.

Fewer but more capable tractors

“In our grains and oilseeds sector, there has been a trend over time of farmers buying and using tractors with increased averagepower output. The number of tractors that these farmers collectively own may have decreased, but the increased power output is allowing them to use the tractors for more tasks. This is just one way in which they are doing more with less.”

Louw cites the comparative example of South Africa’s grains and oilseeds farmers in the 1980s typically only having sufficient tractive power available to prepare and manage four rows of their crops at a time in every pass over a field.

The tractive power and operational efficiencies of tractors had since improved to such an extent that present-day farmers could now haul implements capable of preparing and managing up to 32 rows of their crops in a single pass.

In South Africa’s western parts, where compaction-prone, sandier soils are used to grow grains and oilseeds, commercial farmers now commonly own tractors of at least 120kW power output each that are capable of hauling the deep ripping implements required to ameliorate the sub-oil compaction.

“The various advances in grains and oilseeds production technologies, South Africa’s dry climate, and farmers’ constant efforts to reduce their production costs, are key factors requiring these farmers to plant, manage and harvest their crops at the right times. The windows for these activities are often narrow, so farmers are buying and using tractors and combine harvesters that are capable of doing the work as fast and efficiently as possible,” Louw continues.

He cautions farmers, however, to avoid overcapitalising their businesses by buying new machinery that is “nice to have” or simply unnecessary to the operation. Even when a farm’s financial situation is good, the farmer should first carefully consider whether or not a machine purchase will generate sufficient value for the business into the foreseeable future.

This return on investment should, at the very least, be equivalent to the machine’s combined purchase and operational costs. Ideally, a machine should generate a positive return on investment.

“If a farmer is uncertain about the financial benefits of a potential machine purchase at any given time, he or she should defer making this decision to a time when there is more certainty. But if an existing older machine is costing a farmer more in repairs, downtime and inefficiency than the purchase and operation of a new replacement machine would cost, then the purchase makes sense,” says Louw.

Makube says that technological advances, enhanced operational efficiency goals and the impact of climate change will be key drivers of commercial farmers’ decision-making in terms of their purchases of new agricultural machinery into the foreseeable future.

“The role that commercial farmers, agricultural companies and commercial banks play in establishing more black commercial farmers is starting to show good results. It is through these joint partnerships that we’re seeing capital expansion projects that bring these up-and-coming farmers into the market segment [for new agricultural machinery].”

Rankin says anecdotal evidence suggests that commercial banks appear more willing nowadays to offer financing, such as for new agricultural machines, which contributes to the growth of South Africa’s agriculture sector. In recent years, farmers had reportedly often struggled to obtain favourable financing from commercial banks for purchases of these machines.

Email Dr Jim Rankin at [email protected], Paul Makube at [email protected], and Corné Louw at [email protected].