Photo: Lloyd Phillips

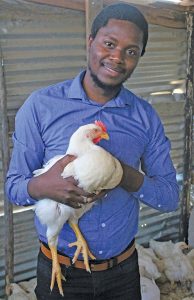

Emmanuel Gumede (26) is a determined young man. He is currently employed full- time as a call-centre supervisor, but his heart lies in fulfilling the big dreams that he has for his 18-month-old, small-scale broiler farming business.

It was only in March 2019 that Gumede began a small production trial in his family’s

backyard with 10-day-old New Hampshire chicks he had bought in a Durban pet shop.

These were the only chicks left when he arrived at the shop that day, and despite New Hampshire chickens having been bred primarily for egg production, he learnt a number of valuable lessons about how to take chickens to maturity.

“At the beginning of 2019, before I bought the New Hampshire chicks, I’d started to search the Internet for as much information as I could find about growing broilers in the backyard,” says Gumede.

“The information I read and YouTube videos I watched were very helpful. My mother,

Ernestina Gugu, also taught me some lessons from her younger years when she raised small flocks of free-range chickens in the backyard.”

A simple, functional chicken house

Scraping together every cent of cash he could spare, Gumede bought materials and built himself a simple 7m x 14m broiler grower house comprising corrugated iron sheets, wooden poles and planks, and an earthen floor.

A bonus was that his family’s property, situated in KwaZulu-Natal’s (KZN) Upper Buffelsdraai area just north of Durban, had an empty rondavel within which he could rear his day-old broiler chicks until they were 14 days old.

They could then be transferred to the grower house for finishing. The rondavel has enough floor space to rear 1 500 broiler chicks, but the 98m² grower house has capacity for no more than 700 fully-grown birds at about seven birds per square metre.

So Gumede buys in only 700 day-old chicks at a time, and rears these for two weeks as a single flock in the rondavel while he grows out and markets the other flock of older birds in the broiler house.

“Through research I settled on the Ross 308 breed for my business, and I buy the day-old chicks from the National Chicks’ hatchery. The informal market that I supply with live birds and cut-and-cleaned carcasses is very size-conscious. The broilers that I grow to five-and-a-half to six weeks old are plump and heavy, and my customers like this. They don’t want to see the scale weight of a bird; they want to pick it up and look at it, and be satisfied that they are getting value-for-money.”

Gumede currently pays R7,50 per day-old chick. The birds are vaccinated against Newcastle disease and Gumboro disease (infectious bursal disease) before they leave the hatchery.

At home, Gumede immediately places the chicks into a simple, pre-prepared enclosure in the rondavel. The cement floor is covered with a thick, soft layer of clean wood shavings.

Even though the property is along the subtropical KZN North Coast, night-time temperatures in winter can sometimes drop to around 10˚C, which is too cold for the sensitive chicks.

If need be, Gumede will switch on domestic electric heaters placed strategically around the chicks’ enclosure to keep the young birds warm. During the hot and humid summers, he uses domestic fans to help keep his older, more heat-sensitive broilers cool.

“For their 14 days in the rondavel, I feed my younger flock De Heus starter crumble. From 15 days old, and once they’ve been moved to the grower house, I feed them De Heus Siyakhula grower pellets ad lib. I’ve calculated that I use about 4,5kg of feed to grow each broiler to marketable size and weight,” he says.

Managing flock health

Gumede keeps his broiler houses as clean and hygienic as possible to minimise the risk of pests and diseases. He ensures that any patches of wet floor covering are removed daily and replaced with clean, fresh and dry wood shavings.

He also thoroughly washes and sanitises the interiors and equipment of the rondavel and grower house between taking the previous birds out and introducing a new batch of birds a week later.

“To boost their immune systems, I give them a ‘stress pack’ of vitamins and electrolytes mixed into their drinking water every three days,” he says.

“I also spend as much time as possible with them. I’ve learnt their sounds and behaviour, and know when they’re contented or something is wrong. If something is the matter, I investigate the problem and treat it specifically. I don’t blanket-treat my birds with antibiotics and other medicines unnecessarily.

“The average mortality rate across my flocks is below the 5% industry standard.”

Of his approximately 670-strong flock, Gumede sells about 400 chickens as live birds to the informal market in the Upper Buffelsdraai and Verulam communities. The majority of the balance are sold as pre-ordered, cut-and-cleaned, fresh or frozen carcasses. Customers for these are also from the two local communities.

Gumede’s mother and some trusted temporary workers hired from the neighbourhood carry out the laborious tasks of slaughtering, feather plucking and carcass-cleaning by hand.

Value-adding

“An interesting recent development has been a growing demand for roasted or braaied, cut-and-cleaned carcasses delivered to households in our community,” says Gumede.

“This takes a lot of time and effort for us, but the value adding generates more profit

per bird sold than through the sales of live birds and uncooked carcasses. We’re looking at ways of being more efficient in our roasting and braaiing so we can capitalise on this growing demand.”

For comparison, he explains that he sells a five-and-a-half to six-week-old live bird for R80, a cut-and-cleaned fresh or frozen carcass for R85, a plain roasted or braaied carcass for R115, and a roasted or braaied carcass with a 1,5ℓ soft drink for R125.

As an added incentive for his often low-income customers, Gumede provides free local delivery.

“I learnt a lot of theoretical lessons from my research into backyard broiler production, but the most important and valuable lessons have been the practical ones learnt through my experiences of managing my own broilers and marketing them,” says Gumede.

“Theory doesn’t always work in practice. I’ve often had to adapt the theoretical advice into what works for me on the ground.”

The future

Gumede has set himself the goal of being a large-scale commercial poultry farmer by the time he turns 35 in nine years’ time. He understands that this will require him to find a suitably large piece of agricultural land to lease or own, and he will focus on finding this when the time is right.

In the meantime, within the next six months, Gumede intends building a second broiler grower house on his family’s property, in which he will be able to finish a further 500 birds at a time to keep up with his growing market.

Email Emmanuel Gumede at [email protected].