Photo: Keri Harvey

Traditional potato farming starts with ploughing the lands, followed by scarifying, putting down gypsum, ploughing and discing the soil again. “In the end, six or seven mechanical processes are involved in planting potatoes. The no-till way takes

ploughing out of the equation,” says Francois Turner.

He is the owner of Turnerland equipment manufacturers and he is currently testing his no-till equipment on land he is renting near Hopefield. Labour problems and high costs led him to manufacture no-till potato equipment. His company is the only manufacturer of no-till potato farming equipment in South Africa. He encourages potato farmers to give no-till a try.

No-till process

“First of all, put in sheep and let them graze the vegetation down,” says Francois. “About 1 200 sheep on 20ha is ideal.’’

‘‘If there is a lot of vegetation, it must be sprayed first. This is cheap and costs about R80/ha. I spray with Erase, which changes the chemistry of the plant and makes it sweet-tasting and delicious for sheep to eat.’’ While they graze, the sheep also compact the soil, and when they are finished, only dry matter is left.

‘‘Then we use a rotary rake to gather the organic matter into rows, and it is baled and used as compost again.” A month before planting, Francois gets a professional to take soil samples for analysis to see exactly what fertiliser is needed. Samples are taken from five different hectare blocks, sent away, and two weeks later a report indicates what is needed. “I use 5-7-5-30% Atlas N-P-K (Nitrogen (N), Phosphorus (P) and Potassium (K)). The pH of the soil is very important to ensure you don’t get brown scab on the potatoes.”

Crops are planted to the edge of the veld to prevent wastage of any land.

At this stage the land is clean but not bare. Then with a single implement, the soil is ripped, fertilised and planted. The soil is opened with a ‘vlekskaar’ plough, working about 500mm deep or 300mm below the seed level. This process ventilates the soil and at the same time puts down the fertiliser, so there is no wastage. Francois uses about 1,5t of fertiliser per hectare and adds some chicken manure. He says some farmers still use broadcast fertiliser spreaders which waste fertiliser, others just plant seed and don’t even fertilise – both are a waste of time and money.

“Never be stingy with fertiliser,” he advises, “For a yield of 70t/ha to 80t/ha, use fertiliser liberally.” Francois adds that the potato plants require phosphate immediately when planted, because it’s the catalyst to absorb the other nutrients in the fertiliser and soil. “We also use Vidate, a yellow band product, for nematode (or eelworm). Then we put down the seed potato about 200mm deep and close up the soil.’’ They don’t cover up completely, as the soil covering the seed is V-shaped to allow the potato tuber to break through the soil easily.

Then, just before the sprouts reach the surface, two to three weeks after planting, all weeds are burnt off the land. “This is very important,” says Francois, “because weeds are stronger growers than potatoes and will choke the crop. We use Eraser or Gramoxone herbicide for the weeds and also wash Lasso into the soil through the centre pivot system to prevent the germination of weed seeds.”

Depending on the soil analysis, when the potatoes have come up after about three weeks, additional nitrogen may also be needed to boost growth. They plant after the first good winter rain, usually around the end of May. This year, due to labour and transport complications they are still planting in July, although normally planting ceases in June. It’s not a problem though because the crop can be irrigated if necessary. “I am experimenting with planting two crops a year, the second planting will be in August, just one circle of 20ha.”

Harvesting

The time between planting and harvesting depends on the variety planted. “I plant BP1,” says Francois, “because it’s a strong grower. It takes four months from planting until we can harvest. I believe that, with irrigation and water from the river, I am taking a calculated risk in planting potatoes twice a year.” When potatoes are harvested traditionally, “you dig about 300mm into the soil to lift the potatoes and then sieve the soil.’’

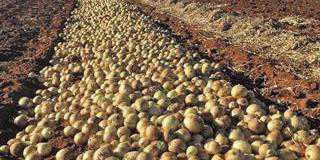

Sheep graze off vegetation before planting. Courtesy of Francois Turner

This process is even worse than ploughing, as you are mixing the soil and organic matter. Buried organic matter causes resitonia or black spot on potatoes, and that then requires more chemicals and expenses to combat. ‘‘With no-till I don’t have this problem because we harvest potatoes with a bulk harvester and with clean soil you will have a beautiful product. If you want a perfect-looking potato, never allow organic matter into the soil.”

Potato pests

“We put down methamidophos that kills cutworm, but this is necessary for all potato farming. There are no additional pests to look out for when cultivating potatoes the no-till way.” Mice in the lands generally indicate a very good soil quality, says Francois, and the traditional methods of ploughing and planting generally kills mice. ‘‘Using just a ripper we don’t really kill mice, so we put down phostoxin tablets from early morning until 2pm to manage them.’’

Benefits of no-till

“I am conserving the land for future generations. No-till is environmentally friendly because we plant right up to where natural veld starts and we don’t remove any natural vegetation. Farmers will also save thousands of rands that would have been spent on diesel and repairs to machinery because of mechanical wear and tear. Beautiful potatoes are produced and yield is high.”

Traditional ploughing methods work organic material into the soil, and this robs the soil of nitrogen, so this has to be supplemented again at additional cost. Cultivating the no-till way doesn’t mix organic material into the ground, it all remains on top of the soil and greatly reduces the need for nitrogen supplementation. Plus, there is no soil erosion because the organic matter on top of the land holds the soil.

“Many farmers think I am crazy,” says Francois, “but it is not necessary to burn up fuel and plough your farm to pieces. Here I have sandy soil, clay and lime soil and no till is no problem. The only time it may not work as well is in very heavy clay soil. And the method applies to all varieties of potato.” Ground-breaking Francois says he isn’t aware of anybody else in South Africa or abroad, farming potatoes this way.

‘‘We first tried it in 2007 and it was a huge success. Then we yielded 40t/ha from dry land. Now on irrigated land, if all goes according to plan, the yield should be no less than 70t/ha. The method does require more attention and is a bit tricky, so many farmers won’t be interested, he says. ‘‘But, as Bill Gates said of the internet ‘it is not a case of wanting it, because you will be swept away by the tidal wave’. I believe that no-till potato cultivation will have the same impact on potato farmers.

Farmers are always looking to cut costs for more profits, and the no-till way does just that. But farmers must leave their old methods behind.” Francois adds that he loves potato farming because it also allows him to test the specialised equipment he builds to ensure it is problem-free. Turnerland machinery is made with minimal parts that need replacing and maintenance, “because farming shouldn’t be a battle”.

“I think farming should be as much pleasure as playing guitar.”

Contact 083 258 5083; email: [email protected]; or visit www.turnerland.co.za