Photo: FW Archive

For over a century, cheap energy and quick results have seduced farmers into producing more and caring less. But the time has come to pay the piper, and the bill is likely to put many farmers out of business.

This is the sentiment expressed by a group of scientists and farmers at the forefront of regenerative agricultural practices.

“The terms ‘crop rotation’ and ‘fallow land’ are as old as agriculture itself. Yet farmers became conceited and turned farms into factories, and this has put us in an input-cost pinch that we need to escape from,” says entomologist Prof Erik Holm.

Holm, the environmental adviser to ZZ2 and former head of the Department of Entomology at the University of Pretoria, was speaking at a recent webinar on the cost of regenerative farming. The event was hosted by Landbouweekblad and sponsored by the Maize Trust, BKB, VKB and others.

“This is where regenerative farming can play a massive role. This type of farming is also known as conservation agriculture and it’s a nature-friendly way of production.

“The problem was never technology, but rather the way in which it was used. Nature-based farming embraces the best technology in harmony with the natural sciences.”

Unfortunately, this change in farming philosophy is expensive and requires overhauling the entire operation in order to embrace regenerative agriculture.

Yet approximately 25% of South Africa’s cash crop farmers have already taken the plunge, while about one-third of all producers have switched from conventional tillage to conservation tillage, according to Dr Hendrik Smith, conservation agriculture facilitator at ASSET Research and the Maize Trust.

A long-term view

Another speaker at the webinar, Prof James Blignaut of the Environmental Governance Department of the School for Public Leadership at Stellenbosch University, concurs that it is initally expensive to switch to regenerative agriculture, which is hampering its adoption rate. However, in the long run, regenerative agriculture is far more profitable.

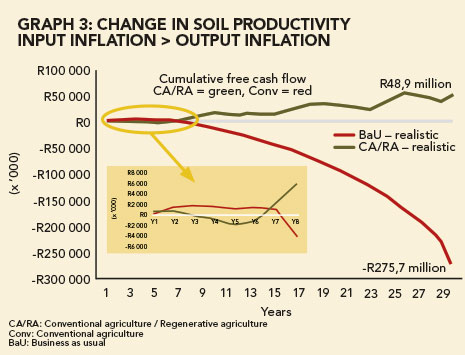

Research has shown that an average piece of land that is tilled using regenerative farming techniques will make an annual profit of around R758/ha after 30 years. But land that is worked conventionally will suffer an annual loss of around R3 297/ha after 30 years.

“That’s a difference in profitability of about R4 000/ha,” says Blignaut.

“This shows that conservation agriculture isn’t merely a buzz phrase; it’s a viable alternative to keep farms sustainable. In fact, if we’re not able to contain current farming costs, studies have shown that it will be the death knell for agriculture.”

Blignaut came to this conclusion after studying the financial implications of switching from conventional to regenerative farming techniques.

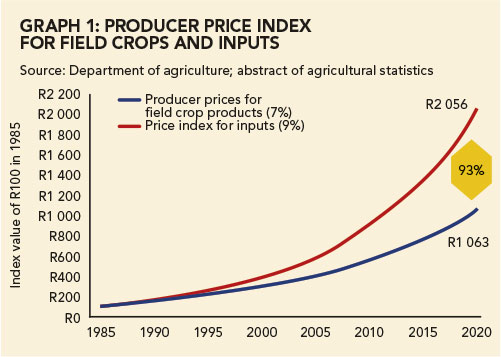

“When we look at the rise of input costs between 1986 and 2014 as recorded by government [see Graph 1], we see a change of 9% per annum. Over the same period, producer prices for field crops increased at an annual rate of 7%.

“This shows a 93% difference in 2020 between the rise in input prices and that of producer prices when compounded annually over the period. This means that the increase in input costs [is almost twice] the increase shown in producer prices over the past 35 years.”

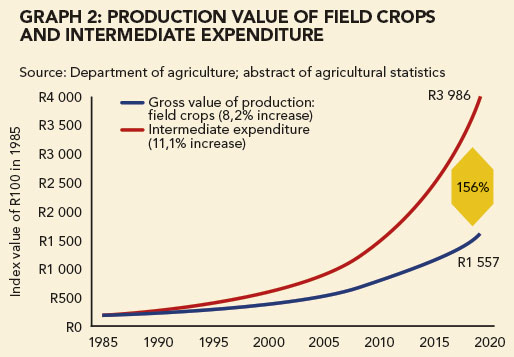

When it comes to production value of South African cash crops and overall farm expenditure, these grew by 8,2% and 11,1% per annum respectively (see Graph 2), which boils down to a compounded difference of 156% over 35 years.

“Basically, agriculture has become unsustainable, and conventional farms are not seeing any real productive growth. The value of capital formation stands at only 5,7%. Due to growing expenses, there’s no money to reinvest in or renew the [sector].”

This, stresses Blignaut, is hampering the sector’s advancement. “The only viable option of escaping this situation is to reduce costs, create multiple income streams and invest in natural capital.”

To ascertain whether regenerative agriculture would be a viable substitute for conventional practices, Blignaut took the on-farm results of the cash crop farms previously mentioned by Smith to determine the long-term viability of regenerative farming. He also looked at equipment costs.

“The nett result showed that cash flow increases when a farmer moves to conservation or regenerative agriculture,” he says. “But farmers should realise there’s an initial higher cost to move to this type of farming [see Graph 3], because they need to change their implementation and buy in extra animals.”

However, producers will eventually save on the cost of replacing equipment, as it is not used as intensively as with conventional farming.

The cost of not changing

According to another speaker at the webinar, US agroecologist Dr Jonathan Lundgren, CEO of Blue Dasher Farm in South Dakota, their studies of US almond producers had shown that regenerative farming was twice as profitable as conventional farming. “Water filtration is six times better on these [regenerative] farms, and soil health has increased by 30%.”

Lundgren believes that US agriculture is in crisis due to a lack of farming diversity

and an over-reliance on pesticides. His research has led him to the opinion that these factors have had a string of negative effects, including the decline of pollinators such as butterflies and honeybees.

“In the US, we’ve seen a growing gap between science and farming communities, because the former isn’t looking at issues that matter to farmers. Scientists have to be part of the agricultural community to understand the issues that really matter on the ground.

“[Producers] have to change their farming ways. If you don’t, it will cost you your farm.”

On his own farming operation, Lundgren does not use herbicides such as glyphosate.

“We use biological competition to manage any unwelcome pests or plants. We’re also

able to make use of fire here in the US, but I’m not sure if that’s a possibility in South Africa. Traditionally, farmers would use tillage or herbicides to get rid of unwanted plants, but in my experience both of these methods have limited success rates.”

A growing movement

According to Smith, one of the main changes that farmers should prepare for when switching to conservation and/or regenerative farming practices is the shift in weed patterns.

“But remember, you’re not alone. Reach out for help; there are others who’ve already walked this path, and you’ll find somebody willing to help you adapt.”

The Western Cape has the highest adoption rate of conservation agriculture at 51%, he adds. This means it is being practised on 804 866ha in the province, which plants 1,569 million hectares annually.

In KwaZulu-Natal, conservation agriculture is practised on 38% (62 956ha) of land. Annually, 164 620ha of crops are planted in the province.

North West has an adoption rate of 37% or 330 464ha; a total of 890 437ha are planted annually.

In Gauteng, the adoption rate is 33% or 57 649ha. The total cropping area stands at 173 435ha a year.

Around 27% or 68 834ha of Limpopo’s land is planted using conservation agriculture methods, and the province’s annual total cropping area stands at 255 866ha.

In Mpumalanga, 24% or 205 598ha of the total annual crop area of 850 484ha makes use of conservation agriculture.

The three remaining provinces are in stark contrast to the rest.

The Free State has a 3% adoption rate, which means that only 73 520ha of the total 2,197 million hectares planted annually are rooted in conservation agriculture. A mere 3 194ha or 2% of the Eastern Cape’s 160 307ha of cash crops are planted using the conservation agriculture system.

The Northern Cape does not use these principles on any of its 69 498ha of cropland. “The province has a unique double-cropping system in place, but doesn’t qualify for conservation agriculture,” explains Smith.

Phone Prof Erik Holm on 015 395 2040, email Hendrik Smith at [email protected], Prof James Blignaut at [email protected], or Dr Jonathan Lundgren at [email protected].