Photo: Dr Mac

Animals are exposed daily to the hazards of the natural environment. They also behave instinctively. In combination, these two factors place them at constant risk of accident, injury and disease.

With this in mind, it’s important that farmers understand how to treat certain medical emergencies in livestock, and that they have the first-aid tools at hand to do so. While an intervention may not be enough to ‘cure’ an animal, it can buy time before a veterinarian arrives, and this could end up saving the animal’s life.

Planning

Keeping an emergency stock of livestock medications on the farm is all very well, but many farmers neglect to check their first-aid kits regularly, and may only realise that products are missing or expired when an animal becomes sick or injured. So, when putting together a first- aid kit for sheep, goats and cattle, ask yourself:

- What diseases, conditions and injuries are most likely to occur? This will help you choose the instruments, medications and materials you will always need available;

- Who will be using the first-aid kit, and does this person have enough training in first aid for animals?

A well-equipped first-aid kit has three separate sections. The first contains injectable medications and vaccines, which normally require refrigeration. The second includes topical medications, sprays and antibiotics, which usually only need to be kept cool. And the third has instruments, bandages, wound dressings and cotton wool, most of which just need to be kept dry and clean.

Livestock remedies that require refrigeration expire relatively early, and the expiry date, together with the optimal storage temperature, is printed on the package. They can be kept in a large, sealed plastic container that fits into the same refrigerator in which you store vaccines. Some injectable antibiotics, notably tetracyclines, should be kept under cool conditions, but not refrigerated.

First-aid components such as soap, disinfectants, gel lubricants, wound salves, powders and sprays can be kept in a plastic tool box. This can be transported easily to the livestock that needs treatment. In the same toolbox you can include a pair of scissors, a rectal thermometer, a stethoscope, sterile needles (green, yellow and pink), syringes (3mℓ, 5mℓ, 10mℓ and 20mℓ), scalpels, blood-collecting tubes and sterile gloves.

Bandages, cotton wool and wound dressings are bulky, so they should be stored in a third container and protected from dirt and moisture.

It’s a good idea to keep the last two containers in a kitchen cabinet close to the refrigerator where you store the medications and vaccines. If the room is fitted with a sink for washing hands and equipment after treating the animals, so much the better.

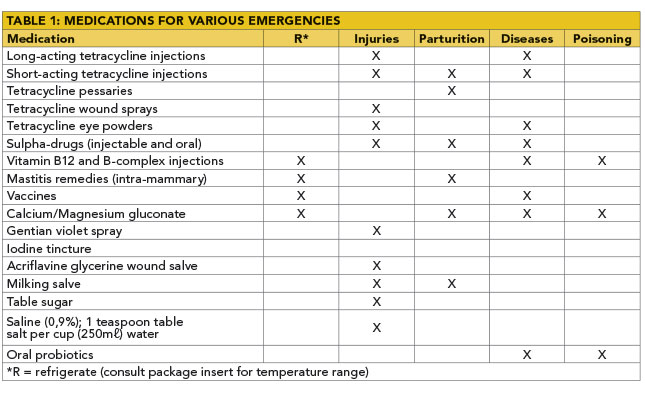

Table 1 shows the medication that is required for injuries, parturition, infectious diseases and poisoning.

Injuries

Injuries to livestock arise from many causes and vary greatly in severity. The following are amongst the more common experienced in South Africa:

Predators

The most devastating injuries are those caused by dogs or other predators. First aid

starts with deciding whether any animals should be culled immediately to prevent further suffering. The next steps are to stop the bleeding, treat for shock and pain, clean the wounds, administer injectable antibiotics, and vaccinate against tetanus.

As a follow-up, use insecticidal wound spray to prevent fly strike. Some cases may need surgery, which must be performed by a veterinarian.

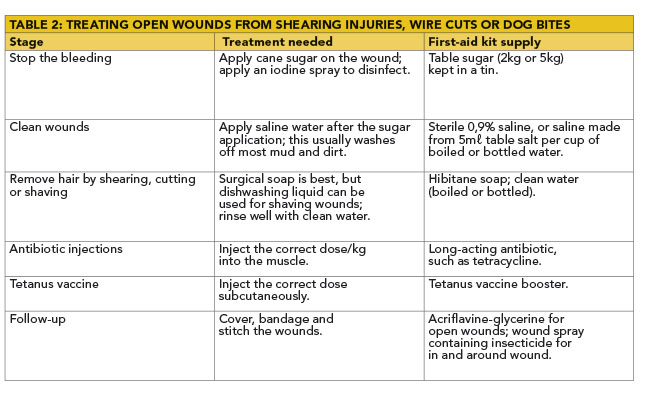

To treat wounds, you’ll need shearing equipment, a pair of curved scissors, a razor to remove wool or hair around the wounds to be cleaned, and syringes and needles for injections (see Table 2).

After you’ve treated the animals, scrub the instruments using soap and water, rinse and dry them, and wrap them in a clean cloth or place them in a Ziploc plastic bag for storage.

Leg fractures

The second-most likely injuries are leg fractures, which occur mainly in lambs, kids and calves. Most fractures that occur below the hock in the hind leg, or the knee in the front leg, can be splinted and bandaged.

Ticks

Ticks can cause wounds or abscesses between the claws in sheep and goats, and excrete toxins that damage the ears and tails of calves. Inject regularly with ivermectin or moxidectin or apply tick grease to the affected areas. Clean the wounds with salt water, and apply acriflvine/glycerine.

Snakes

Snakes are a danger to livestock, and cobras can spit venom into their eyes. If an animal with reddened eyes is frantically rubbing its face against a fence-post, wash its face with saline solution, or use a hosepipe to wash the venom off the eyes and skin.

If an animal has a large, painful lump on its body or legs, look for two tiny punctures, 2cm to 3cm apart, near the centre of the swelling. Paint iodine or rub betadine ointment on the swollen area.

Bleeding

An animal can bleed out fairly quickly if the wound is severe enough. This is why it is important to know how to stop the flow of blood, before medical help arrives.

Take a jacket or overalls (any type of material) and push hard onto the bleeding wound.

The pressure should be severe enough to ease the flow of blood. If you don’t have a blood-flow restriction kit, which usually includes a tourniquet, you can secure the jacket with your belt. Tie the belt tightly enough to restrict blood flow. It may also be easier to have someone hold the jacket in place while you tie the belt (or even rope) around it.

Parturition

An emergency can easily arise during birthing.

Twin lamb disease (sheep) and milk fever (cows)

In twin lamb disease, which is triggered by inadequate nutrition, the ewe shows drowsiness, separates from the flock, and is reluctant to feed. In the case of milk fever, which is caused by a lack of calcium, the cow is restless, then lies down and refuses to get up. These conditions can prove rapidly fatal if left, but both can be treated with calcium gluconate.

Complicated birth or retained afterbirth

These can lead to infection and may therefore require a uterine pessary. Wash the vulva and surrounding area with soap and water, then use a long plastic glove and lubricant to insert the pessary.

Mastitis

This is inflammation of the udder caused by an infection, and leads to a drop in milk yield and quality. To treat it, apply an antibiotic (from a veterinarian), either by injection or using an intra-mammary infusion via each infected teat.

Newborn calf not suckling

If the newly born calf refuses to suckle, use a milking salve and milk out the cow’s colostrum (first milk) into a sterilised bottle. Then attach a special calf teat for the calf to suckle (see page 83 for more information on helping the kid, lamb or calf feed on a bottle).

Scours (diarrhoea)

Newborns are prone to scours, and the resulting dehydration can be life-threatening. A vet can supply rehydration fluid with probiotics to be given orally. Use sulphonamides or other coccidiostats for coccidiosis-induced scours, and oral or injectable antibiotics for bacterial scours.

Scours also occurs in adult animals. Rehydration and probiotics work well for symptoms, but diagnosis is important. Causes include feed imbalance, poisons and parasites. Take a fresh sample of faeces from affected livestock to your vet so that treatment can be matched to the cause of the disease.

Infectious and contagious diseases

Infectious diseases are often seen in livestock. Symptoms vary, but a high rectal temperature (above 39°C) is common to the diseases described here.

Heartwater

Although controlling vectors such as ticks and midges can reduce cases, heartwater remains a problem in sheep, goats and cattle. Treatment involves intramuscular injection of a long-acting tetracycline, anti-inflammatory medication and injectable B-vitamins.

Redwater and anaplasmosis (gallsickness)

These are found in cattle. Consult a veterinarian for advice on remedies for blood parasites, so you can include them in your first-aid kit.

Bluetongue, three-day stiff sickness and lumpy skin disease

There is no recognised treatment for these three diseases, and vaccination is therefore important. However, oral or injectable painkillers, obtained from your vet, can decrease symptoms and improve the chances of survival.

Pneumonia

This is caused by bacteria or viruses, and is brought on by rainy, wet conditions. Animals may struggle to breathe (and ultimately die) due to blocked nasal passages. Use tissues and saline solution to clean the animals’ noses, and consult a veterinarian about antibiotics.

Eye infections

Rinse the animal’s eyes with saline solution, wipe with a tissue and treat with tetracycline eye powder.

Poisoning

Poisonous plants are a major cause of sudden death in cattle, sheep and goats. Cyanide poisoning occurs when ruminants consume a large quantity of green grass or Namaqualand daisies. Deaths can be halted quickly by moving the herd or flock away from the green grass and mixing 500g of sodium thiosulphate (hypo) into every 100ℓ of drinking water for three days.

Bloat (excessive gas in the rumen) can be fatal in cattle. It normally occurs in spring,

when the grass is lush. To treat it, dose immediately with cooking oil mixed with an equal volume of ice water at a ratio of 100mℓ cooking oil per 100kg bodyweight. (Using ice water will ensure that the animal tastes the oil and doesn’t breathe it in.)

Administer using a bottle on the side of the mouth. Only use a stomach tube if you know how to do it correctly, otherwise the oil may end up in the lungs. A rumen cannula (a small rubber porthole allowing access into the rumen) can be used to reduce bloat in a life-threatening situation and cooking oil can be poured through this as well.

If the type of poisoning is unknown, dose with activated charcoal, mixed with water, orally.