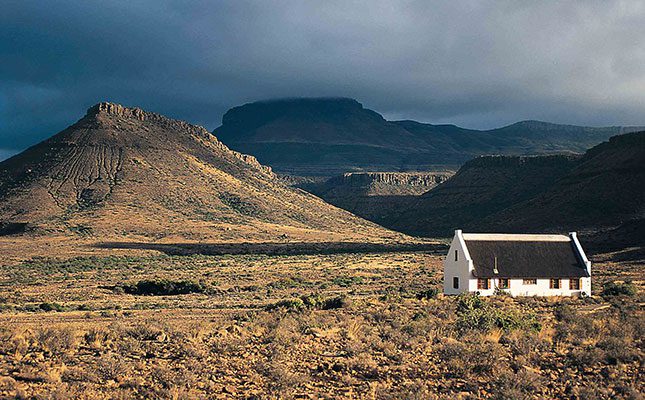

Photo: Wikimedia Commons

Municipal law and related municipal matters are what the firm of Len Dekker Attorneys specialise in. Normally we appear in disputes against a municipality.

Seldom, such as in the case of the Rural Forum against the Thaba Chweu Municipality, do we appear on behalf of the municipality. Thaba Chweu Municipality includes rural areas such as Lydenburg in Mpumalanga.

The municipal property rates dispute in the Supreme Court of Appeal (SCA) was levied on farm properties (as opposed to urban or residential properties) during an eight-year period from 1 July 2009 to 1 June 2017.

The factual background is briefly that prior to the advent of the new constitutional democracy in South Africa in 1994, farms in general were excluded from the rateable properties within the jurisdiction of municipalities.

Consequently, the farm owners were not levied municipal rates for their properties. In establishing the local sphere of government, the new Constitution provides that “the local sphere of government consists of municipalities which must be established for the whole of the territory of the Republic”.

As a result, every patch of land in the country, including farms, fell under one or other municipality. For the first time, farm owners became liable for payment of municipal rates levied on their properties, as a source of revenue for the municipality.

Discontent

This development, compounded by the fact that the levying of the municipal rates was unlawfully implemented by the municipality, caused discontent on the part of the farmers whose properties fell under its jurisdiction.

In 2008, and in anticipation of the municipal rates being levied, the farm owners resolved to establish a voluntary association, named the Thaba Chweu Rural Forum (the appellants).

The appellants’ purpose was, among others, to represent the farmers in their engagement with the municipality, mainly on the issue of levying municipal property rates.

Some of the farmers have been refusing to pay the rates levied since inception in July 2009

As an attorney, my point of view was that a lesser amount was payable by farmers in respect of property rates. A refusal to pay any rates would be tantamount to an unlawful tax boycott.

The legal framework for the levying of municipal property rates has its origin in Section 229 of the Constitution, which empowers a municipality to impose rates on property and surcharges on fees for services provided by or on behalf of the municipality and, if authorised by national legislation, other taxes, levies and duties appropriate to local government.

The national legislation is the Local Government: Municipal Property Rates Act No. 6 of 2004. Section 3 of the act provides that a municipality must exercise its powers to levy rates, subject to the other sections of the same act, including the regulations promulgated by the Minister of Provincial and Local Government in terms of Section 19 of the Rates Act, as well as the rates policy adopted by the municipal council in terms of Section 14 of the act.

Section 8 of the act authorises the municipality to levy different rates for different categories of properties. The categories of properties for levying rates are determined according to the actual or permitted use of that property and its location within the municipality.

The regulations as published by the minister in terms of Section 19 of the act determined that the effective rate to be levied on agricultural properties conducting crop and/or animal farming may not exceed 25% of the effective rate levied on residential properties.

The rates are generally determined as the amount in a rand, calculated on the market value of the property, which market value is in turn determined by a municipal valuer appointed by a municipality.

Valuation

The valuation of the properties is published in the valuation roll valid for a four-year period. The appellants allege that between 2009 and 2017, the municipality failed to meaningfully comply with the provisions of the act, the regulations and the council’s own policy concerning the levying of property rates and granting of rebates.

The appellants contended that in determining the rates payable, the respondents failed to consult with the population in the area, as prescribed by law.

Each financial year, the municipality levied excessive rates above the 25% prescribed ratio for agricultural properties and failed to comply with the process allowing objections to the valuations in terms of Section 49 of the act.

Market value increases

As a result, there are recorded examples of farm properties that experienced sudden massive increases in market value, such as a company known as Moon Cloud 25 (Pty) Ltd, whose property’s market value appreciated from R1 160 000 since the 2009 initial valuation to R12 180 000 in the 2014/15 second valuation roll.

That increase in market value of the property translated in the levied rates of that property escalating from R1 432,08 levied in the 2013/14 financial year to R149 448,60 levied from 2014/15 and subsequent financial years.

For each of the years between 2009 and 2017, the appellants attempted, without success, to persuade the municipality to enable public participation in the process. In 2017, the appellants turned to the high court for appropriate relief.

The relief sought against the municipality was that it be ordered to deliver to the appellants their members’ property rates accounts for the period 1 July 2009 to 1 June 2017, including the notices published and resolutions adopted by the municipal council concerning the determination of the rates, as well as copies of minutes of meetings held concerning the rates, and ancillary relief.

After receiving some of the documents from the municipality, it became evident that not all the appellants’ members were conducting agricultural farming in crops and/or animals as defined, and therefore some of them did not qualify for the rates determined for the agricultural category of properties.

Some of these excluded members’ farms fell under categories of properties conducting business in game-farming, hospitality and residence. These categories were not to be levied at the rates that are the subject of the dispute in this case.

The appellants farmer members sought relief, in essence that the rates published annually in terms of Section 14(2) and (3) of the act, as well as publication of further rates notices in newspapers and the resolutions of the municipality’s council, authorising the publication of such rates notices, be declared unlawful and be set aside.

Further, that the municipality be directed not to levy property rates on any farm or agricultural property in its municipal area at a rate exceeding the prescribed ratio of 1:025, that is, 25% of the effective rate applicable to the residential property, as contemplated in Section 8 of the act.

Inconsistent

The municipality in their response conceded that at all relevant times mentioned in the founding affidavit, the levying of property rates on agricultural farms, the adoption of resolutions by the municipal council concerning the rates as well as the published notices concerning the impugned rates were inconsistent with the act, and therefore unlawful and invalid.

These factual allegations were not disputed. In fact, the municipality conceded that much. However, though the municipality did not dispute that their predecessors acted unlawfully, they remained opposed to the order sought by the appellants to have the impugned property rates set aside.

A clear distinction has to be made in law between:

- Declaring government decisions unlawful and invalid; and

- Setting aside such decisions and ‘undoing’ it, that is, setting aside the impugned rates.

- The basis of opposing the relief was that the appellants delayed instituting the litigation.

The municipality further contends that consequent to such delay, a retrospective invalidation of the rates levied will impact on the budgets approved in the previous financial years, resulting in prejudice to the municipality and its residents.

The prejudice lies in the fact that the subsequent budgets, of which the municipal rates were an integral part, were determined and are reliant on the basis of the budgets of the preceding financial years.

As such, it would not be feasible to ‘turn the clock back’, as it were. The farmers were aggrieved that the Mpumalanga Full Court did find the levying of the rates unlawful, but due to the delay declined to set it aside.

The Farmers Forum thus approached the SCA to have the unlawful and invalid property rates, set aside and be ‘undone’.

The SCA confirmed an earlier judgment that rates are an integral part of the budget process.

Where the party that challenges the validity of the proclamation of the rates took a long time to approach the court for relief, the court found it would not be in the public interest to set aside the impugned rates.

The court used Section 172 of the Constitution, which provides that where conduct that is inconsistent with the Constitution is declared invalid, the court may make an order that is just and equitable.

The court thus has a wide discretion to be exercised judicially to declare conduct invalid, and to not set it aside but to make an order that is both practical and also just and equitable under the circumstances.

The period of delay in instituting litigation can be a deciding factor in addressing the question to what extent ‘the egg can be unscrambled’.

In the Thaba Chweu case, the court found that there was unreasonable delay on the part of the farmers to approach the court.

They were also misguided by their motive refusing to pay any tax, which point of view was later abandoned when they indicated that they were pressured to pay what was legally due.

The SCA again endorsed the principle of legality as part of the rule of law and stressed that municipalities must “conduct their affairs within the confines of the law”. The court stressed that a trend should not develop where there would be no consequences when municipalities function outside the parameters of the law.

Although the rates notices were declared unlawful and invalid to the extent it related to agricultural properties, they were not set aside.

The municipality was authorised to recover the rates within the legally permissible limit of 25% of residential rates.

The municipality was ordered in future not to levy rates on agricultural property in its municipal area of jurisdiction at a rate that exceeds the legally prescribed rate.

The court struck a balance saying: “Just as the process of agricultural food production by the taxpayers has to be protected, the inflow of revenue for the municipality must also not be disrupted.”

Phone Len Dekker Attorneys on 012 346 8774.