Urbanisation is the result of urban population growth, urban expansion, namely the reclassification of rural areas to peri-urban or urban, and migration from rural to urban areas.

This process is fast-changing, context specific and driven by intertwined factors, including diverse economic developments, such as increasing agricultural productivity, policy choices, availability of natural resources, and external stressors such as conflict, climate extremes or environmental degradation.

Many parts of the world have rapidly urbanised since the Second World War, with the urban share of the world’s population rising from 30% in 1950 to 57% in 2021. It is projected to reach 68% by 2050.

Changing patterns of demand

Urbanisation contributes to the transformation of agrifood systems by reshaping spatial patterns of food demand and affecting consumer preferences, changing how, where and what food is produced, supplied and consumed.

These changes are affecting agrifood systems in ways that are creating both challenges and opportunities to ensure everyone has access to affordable healthy diets.

With urbanisation and rising incomes, households often eat greater and more diverse quantities of food, including dairy, fish, meat, legumes, fresh fruits and vegetables, as well as more processed foods.

This, together with population growth, implies substantial increases in the production and supply of these types of food to satisfy increased demand.

This, in turn, as urban populations grow, translates into vast increases in the total amount of food that agrifood systems have to produce, process and distribute over time.

There may also be slower growth or even declines in demand for other food products sold, such as traditional grains, maize, roots and tubers.

Adjustments in the quantity and quality of food demand and supply bring about changes in markets and retail trade; midstream food supply chains (changes in post-harvest systems for logistics, processing, wholesale and distribution); rural input markets; agricultural technology; and the size distribution of farms.

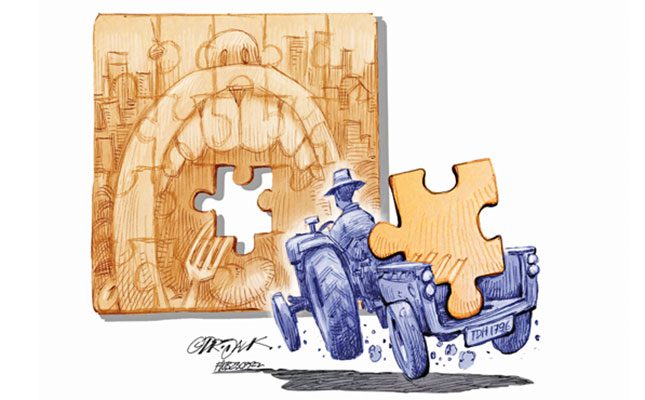

Thus, agrifood systems are transformed, from traditional and mostly rural systems based on local market linkages and farming employment, to systems with greater connectivity between rural areas, and between rural, peri-urban and urban areas.

This entails more complex rural-urban market linkages across a spatial and functional rural-urban continuum, and more diverse employment opportunities along the food value chain, including processing, marketing and trade.

It also entails more dependence on income and food pricing (affordability) for dietary choices, as there is a greater dependence on purchased foods.

Of specific concern against this backdrop are the changes in the supply and demand of nutritious foods that constitute a healthy diet; their cost relative to foods of high-energy density and minimal nutritional value, which are often high in fats, sugars and/or salt; and their cost relative to people’s income (their affordability).

While urbanisation is not an agrifood systems driver in isolation, it changes agrifood systems in interaction with other drivers including income growth, employment, lifestyles, economic inequality, policies and investments.

The ways in which urbanisation is affecting three major components of agrifood systems include: i) consumer behaviour and diets; ii) midstream (logistics, processing and wholesale) and downstream (markets, retail and trade) food supply chains; and iii) food production.

Changes across agrifood systems affect physical, economic, sociocultural and policy conditions that shape access, affordability, safety and food preferences.

These food environments reflect a complex interplay among supply-side drivers including food pricing, product placement and promotion, and demand-side drivers including consumer preferences and purchasing power.

The interplay of supply and demand is key to understand how urbanisation drives changes in agrifood systems, affecting access to affordable healthy diets.

Higher average incomes, combined with changing lifestyles and employment, are driving a dietary transition.

This transition is characterised by changes in the types and quantities of food consumed, with diets shifting beyond traditional grains into dairy, fish, meat, vegetables and fruits, but also into consumption of more processed foods and convenience foods or food away from home.

These changing preferences are reinforced by the greater diversity of both food products and places to buy food in urban food environments, ranging from supermarkets to informal markets, food street vendors and restaurants.

The increased availability of these options often results in increased food consumption and dietary diversity.

The role of marketing

Dietary preferences are shaped by marketing and other supply factors, with a reinforcing compounding effect on the food produced, supplied and consumed.

However, urbanisation has contributed to the spread and consumption of processed and highly processed foods, which are increasingly cheap, readily available and marketed, with private sector small and medium enterprises and larger companies often setting the nutrition landscape.

Cost comparisons of individual food items and/or food groups from existing studies indicate that the cost of nutritious foods – such as fruits, vegetables and animal source foods – is typically higher than the cost of energy-dense foods high in fats, sugars and/or salt, and of staple foods, oils and sugars.

The relative prices of nutritious foods and foods of high energy density and minimal nutritional value have also been shown to differ systematically across income levels and regions.

With urbanisation, purchases from super-markets, fast-food takeaway outlets, home deliveries and e-suppliers and are increasing.

In Latin America and the Caribbean, there has been a profound shift in the last 20 years towards foods of high-energy density and minimal nutritional value, including sugar-sweetened beverages.

While this phenomenon occurs predominately in urban and peri-urban areas, it is spreading to rural areas and indigenous peoples’ lands.

Meals away from home

There has also been a shift towards increased consumption of food away from home and snacking, which corresponds to high levels of overweight and obesity among all ages, along with high burdens of stunting in some countries. Many settings now face multiple, simultaneous burdens of different forms of malnutrition.

Another reason for the spread of processed foods is convenience. Urbanisation is associated with changes in the lifestyles and employment profiles of both women and men, as well as increasing commuting times, resulting in greater demand for convenience, pre-prepared and fast foods.

Women, who often bear responsibility for food preparation, are increasingly working outside the home, and thus may have less time to shop, process and prepare food. At the same time, men are increasingly working far from home in other cities.

These trends are driving the purchase of pre-prepared or ready-to-eat cereals such as rice and wheat along with more processed foods and food away from home prepared by restaurants, canteens, retailers, etc.

The food-processing sector and fast-food segment have grown quickly as a result. For example, eating patterns of Tanzanian migrants change when they move from rural to urban areas, away from traditional staple foods such as cassava and maize, and towards convenience, ready-to-eat or pre-prepared foods such as rice, bread and food away from home.

Increasingly, this trend is occurring in rural areas as a time-saving measure for off-farm labourers and women working outside the home, facilitated by increased rural incomes, increased supply of these foods from urban and other rural areas, and reduced transportation costs because of better roads.

The diet in rural areas has shifted from mainly home-produced foods to market-purchased products.

In Eastern and Southern Africa, rural households buy 44% (in value terms) of the food they consume.

Consumption of processed foods is higher in urban areas, in terms of the proportion of expenditure on food, but rural consumption of processed foods is not much lower.