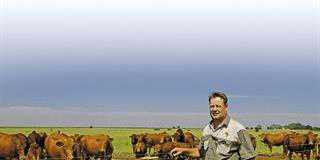

Photo: Siyanda Sishuba

Bookholane Mokoena farms on 270ha of leased land near Nigel in Gauteng. He started farming in 2015 and has since managed to increase his herd from 36 mixed-breed cattle to a 90-head Bonsmara stud herd.

Mokoena grew up in the Free State, where his father was a subsistence farmer, and he developed a passion for agriculture from a young age. After matriculating, however, he did not have enough money to go into farming, so he took a job with Sasol.

He saved for years to accumulate start-up capital, and finally resigned in 2015 to begin his career as a farmer.

Although keen on stud breeding, he could not afford this immediately. Undeterred, he farmed sheep on leased land in the Free State to generate further savings and searched for more land, eventually finding the farm he currently leases near Nigel.

Mokoena has also applied for access to land through the Department of Agriculture, Rural Development and Land Reform (agriculture department), but is still waiting for his application to be approved.

His research into various cattle breeds for stud breeding finally led him to the Bonsmara. The prominence of the breed in South Africa means that plenty of good-quality genetics are available, he says. In addition, the breed is well-adapted to the area in which he farms.

In 2016, Mokoena crossed paths with the man who was to become his mentor: Arthur de Villiers of Arcadia Bonsmaras in Vrede in the Free State. De Villiers is also a chief inspector of the Bonsmara Cattle Breeders’ Society of South Africa (Bonsmara SA).

Under the guidance of De Villiers, Mokoena sold all of his mixed cattle and bought Bonsmaras instead. He also joined Bonsmara SA in May 2016 and says he has benefitted greatly from the assistance he has received from the society.

As a stud breeder, his purpose is to service the needs of commercial breeders. The challenge, however, is the limited size of his land, which makes it impossible for him to increase his herd to more than 100 animals.

Grazing and weed problems

The farm has eight grazing camps with mixed veld. Each camp has a water point fed from two boreholes. Pumping water from these accounts for one of Mokoena’s largest farm expenses.

When he had fewer cattle, Mokoena was able to implement a rotational grazing system, but since the herd has grown, it has become increasingly difficult for him to manage the grazing so that camps get enough time to rest and recover before being grazed again.

This, he says, is the major reason he is trying to get access to more land via the agriculture department’s land reform initiatives.

Another difficulty is that the quality of grazing on the farm has deteriorated due to problem weeds such as slangbos (Seriphium plumosum), an unpalatable invader. Mokoena has responded with a control programme.

“The weeds need to be removed manually and this requires hiring temporary labour,” he says.

With access to more land, Mokoena would be able to plant maize to supplement the natural grazing.

Herd management

Mokoena aims to maintain a bull-to-cow ratio of about 1:25 for proven mature bulls and 1:15 for young bulls. His breeding herd comprises four bulls and 63 cows, and he uses only natural breeding methods.

Stud bulls to be registered with Bonsmara SA undergo visual inspection and fertility testing at 18 months old.

The first breeding season runs for four months from November, and female animals undergo a pregnancy test in March.

The conception rate normally averages about 90%, and all female animals that fail to conceive are moved to another camp and given another chance to conceive during the second breeding season, which runs from April to June. Animals from this group are given another pregnancy test in July, and female animals that have again failed to conceive are culled.

Most of the female animals calve in early spring when the pastures are regrowing. Calves are weaned during the December holiday season, when weaner prices are usually higher.

“To help maintain cattle in good condition in winter, we provide a phosphate winter lick to supplement minerals, such as phosphorus and sodium, in their diets,” says Mokoena.

Fit, not fat

In summer, with the abundance of grass, there is a risk that the animals can get too fat, and this can negatively affect fertility, he says.

To ensure this does not happen, he sometimes moves the bulls to camps that offer less grazing.

Mokoena selects for medium-framed bulls that will produce calves with lower birthweights of between 27kg and 32kg, and hence ensure ease of calving.

In addition, he explains, calves with high birthweights are sometimes less efficient than those that are lighter at birth. The bulls and cows are replaced every five years.

Proper records are kept, and calves are weighed three days after birth, then again at seven, 12 and 18 months to monitor growth and weight gain.

“Stud auctions are controlled by Bonsmara SA, and any cows and heifers that don’t meet the breed’s strict criteria for stud animals are sold to commercial breeders,” says Mokoena.

He achieves a 100% calving rate and 90% weaning rate, and ascribes this discrepancy largely to predation by stray dogs, jackal and caracal.

“In 2020, I lost two out of 19 calves, but mortality is generally low,” he says.

“In 2019, I was hit by an outbreak of black quarter and lost about seven animals. It’s a common disease that must be controlled with the help of government vets.

“Another common disease here is bovine tuberculosis. I get assistance from a private vet, Dr Louise van Jaarsveld, who gave me a disease management programme.”

Mokoena says that one can tell from looking in its eyes whether an animal is healthy or not.

“When it’s healthy, a Bonsmara has smiling eyes.”

Email Bookholane Mokoena at [email protected].