Photo: FW Archive

There are good tools available to improve production and yield in layer hens. Established poultry layer genetics companies produce guidelines and performance recording software programmes for commercial layer managers.

For example, on the Hy-Line website clients can access the Hy-Line Red Book (an online management guide), the EggCel flock performance recording software and a layer house lighting application programme.

“Egg producers can set growth and egg production targets for their hens and manage accordingly,” says Dr Aidan Leek of Hy-Line.

“Results can be compared to breed standards to check and correct for flock under-performance.”

A good start

Effective nutrition for laying hens begins in the pullet rearing phase and affects the layer flock’s performance potential.

“If the genetics of the laying birds is the building’s foundation, the rearing phase is the actual construction. If you get the rearing phase right, you’re halfway towards having a successful laying flock.”

Right from the day they are placed in a rearing house the layer chicks must have well-managed brooding, and easy access to feed and water.

“All the chicks should have feed in their crops 24 hours after placement in the rearing house,” says Aidan.

“Buyers of point-of-lay pullets should get growth performance figures for the flock from the rearing operation. These figures should meet, or exceed by up to 10%, the breed’s target growth curve during rearing.”

Avoid stress in pullets, says Aidan. When stressful, but necessary interventions, such as vaccinations, are needed, provide additional vitamins and electrolytes, or increase nutrient density to help the birds cope without any growth loss.

“We want pullets to grow to target weight with as high a feed intake as possible. If they exceed the 10% above target limit then the nutritional content of the feed (but not its quantity), can be adjusted to slow growth.

Dietary changes in the rearing phase must be implemented according to the flock’s average bodyweight, not according to flock age. If a flock is behind target weight at a particular age, then rather keep them on the existing ration until they get to target weight before changing the ration.”

Feed strategically

There are various diet strategies. The ‘three diet’ programme typically feeds a starter, then a grower, and finally a developer feed ration by point-of-lay.

However, Aidan and Hy-Line prefer clients to follow a ‘five diet’ strategy that will “get the birds off to a good start in the first three weeks with a high-density Starter 1 diet”. This is followed by grower and then developer rations.

Finally, pullets are conditioned to enter point-of-lay, and to higher calcium-content rations, with a pre-lay ration. Aidan recommends that the pre-lay ration be brought in a week or two before the start of laying.

“Control the pullets’ gut health by making sure drinking water quality is good which also helps prevent diseases like coccidiosis,” Aidan says.

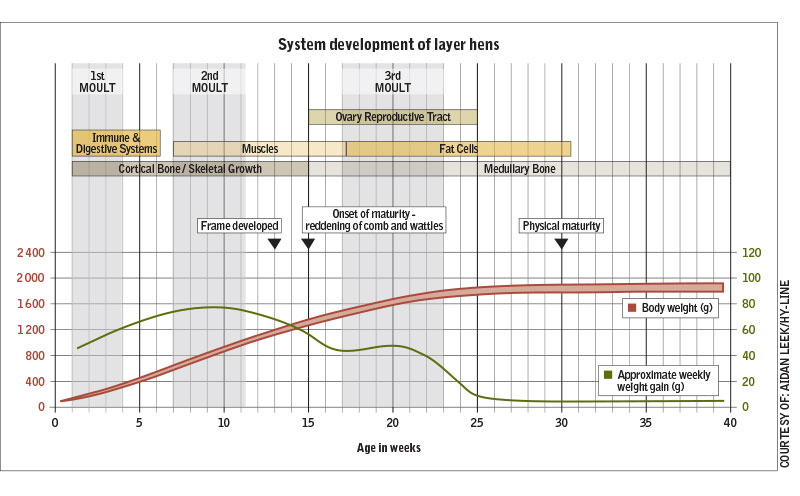

A layer does not grow isometrically; different body parts develop at different rates.

In the first six weeks the immune and digestive systems develop.

During the first 15 weeks the skeleton, internal organs and muscle mass develop; at 12 to 13 weeks layers have almost achieved mature skeletal frame size; from 15 weeks to 25 weeks hens develop ovaries and the reproductive tract; from around the middle of the rearing period until mature weight they are developing fat cells, and from 15 weeks to around 32 weeks they are developing the medullary bone type which acts as a calcium reservoir and reserve.

“So the most important period in rearing, when the birds must be on target weight or slightly above, is from six weeks to 13 weeks by which time a layer pullet’s skeletal frame is 95% developed. A bird not at target bodyweight at 13 weeks will not have her full egg production potential when she comes into lay,” says Aidan.

The rearing operation should weigh birds weekly from three to four weeks, and at least 85% of the pullet flock should be within 10% of the average bodyweight of the flock by point-of-lay.

A layer bird’s feed intake is determined by its nutritional requirements and physical intake capacity. Feed requirements are influenced by genetics that determine the layer’s breed, size, and potential egg production. Higher producing flocks generally eat more. The layer’s effective temperature is influenced by factors such as environmental temperature, air speed around the bird, and feather cover.

A layer’s feed intake can also be affected by feeder space per bird, stocking density in a rearing or layer house, the depth of a feed trough, and the availability, composition and characteristics of drinking water.

Layer birds’ beaks should be correctly trimmed so that their ability to eat and drink is unaffected says Aidan. Feed of the correct particle size should be presented.

“The bird’s health affects feed and water intake. Nutrient density affects intakes. If, for example, the feed is high in energy the layer will tend to eat less. Her calcium appetite influences feed intake, and protein levels, particularly of lysine, in the feed will influence how much she eats,” says Aidan.

Behaviour in management

For the right feeding programme, the manager needs to understand typical bird behaviour during the egg production cycle says Aidan.

“In a trial where in-lay hens were given ad lib access to feed, in a natural light housing environment, it was found that from midday birds tended to start eating more. Feed consumption peaked between 4.30pm and 6pm before dropping off from 6.30pm. From sunrise until about 12.30pm trialled birds consumed between 6g to 8g/ hen/ hour. In contrast afternoon consumption averaged 9g to 10g/hen/hour.

“Layer flock managers often feed more in the first half of the day, which is actually not what the birds want under natural conditions. Intakes are higher in the afternoon because this is the time a hen forms her next egg and she needs calcium to form the egg shell during the night. “Hens also like to fill their crop before it gets dark.”

“A very similar feed intake pattern will be seen on non-egg laying days. In hot conditions, stimulating afternoon feed consumption can be challenging and midnight feeding can be useful.”

Aidan recommends that managers encourage increased feed intake by running feeding tracks often for short periods, particularly when the flock is young. The movement of the tracks stimulates feeding.

He advises that floor-reared and free-range layers should not be fed during peak laying time because they need some peace in their nest boxes to be able to lay. “Ideally, feed should be carried out before and after peak laying times.

“I feel it is important that layers are offered a final feed about an hour or two before the house lights are turned off or before the sun goes down. This will satisfy the natural requirement to have a high feed intake towards the end of the day.

The last feeding will leave calcium in a bird’s gut during the night when she transfers calcium for egg shell production. This is especially important for layer breeds with early morning laying periods.

“If a hen doesn’t have the calcium in her gut she will mobilise calcium from the medullary bone, something which a flock manager doesn’t want,” Aidan explains. “Sufficient calcium in the gut improves egg shell quality.”

Nutrition

The energy targets for Hy-Line’s layer breeds give managers in countries other than the USA, a basic idea of energy requirements, as nutritional values in feed vary. The key is to ensure that layers are not over- or under-fed energy and consulting with qualified poultry nutritionists is advisable to avoid this.

“Managers should not fixate on the crude protein (CP) content of the ration but must understand the impact of amino acids on egg production.”

A benefit of working with digestible amino acid systems to formulate the protein content of layer rations is that it can allow a reduction in the CP content. Benefits of this include reduced excretion of environmentally damaging nitrogen from layers, reducing the feeding of non-essential nitrogen to birds, lowering costs and improving health and digestive efficiency.

Amino acids in a layer feed ration should be balanced for maximum benefit without unnecessary cost. “Nutrition management from rearing to culling the spent layer flock is one of a number of other key factors playing a role in influencing egg size to suit a particular market market demand.

“Amino acids in the ration’s protein content are key nutrient drivers that influence egg size; especially the sulphur amino acids, methionine and cystine. If methionine levels in the ration are reduced to control egg weight, production will drop and sizes can

actually increase if cystine levels are not also reduced.”

For more information email Dr Aidan Leek at [email protected] or visit www.hyline.com.

| Feed intakes in layer birds

A 1,9kg bodyweight layer at 90% production, that lays a 62g egg in a house at 20ºC, has a daily energy requirement of about 1,49 megajoules (Mj). To achieve this while consuming an 11,7 Mj energy content ration she must eat 127,4g/day. When this hen produces a 63g egg in the same conditions her daily energy requirement increases to 1,5Mj. On the 11,7Mj energy content ration she needs to eat 128g/day, an increase of 0,5%. If production drops to 87% with the hen laying a 62g egg (same conditions) her daily energy requirement will fall to 1,475Mj. On the 11,7Mj energy content ration she must eat 126,1g/day or 1,1% less. At 15ºC, producing a 62g egg at 90% production, the daily energy requirement will increase to 1,578Mj. On the 11,7Mj energy content ration the hen must eat 134,9g/day or 6% more. If the energy density of the feed is increased to 11,9Mj and the hen is still producing a 62g egg at 90% production in 20ºC, her daily energy requirement will be 1,49Mj. On the 11,9Mj energy content ration she needs to eat 125,3g/day which is 2,7% less. Information courtesy of Leeson and Summers, 2005 |